In the first part of this article we will try to identify the origins and specific elements of the current crisis in relation to the classic model of cyclical crisis in the capitalist system. In the second part, we will address the critiques of the various policies applied so far to confront it.

1. The Essential Traits of the Crisis in the Capitalist Mode of Production

Generally speaking, a system finds itself in crisis when it’s very functioning generates forces which damage and destroy it. In other words, a crisis is nothing more than a cumulative process in which an autonomous primary implosion, rather than creating secondary effects that cancel it out, creates secondary effects that amplify it.

In the market economy system, crisis is reflected by the simultaneous existence of overproduction in relation to effective demand and underproduction in relation to potential, the former being the consequence of the latter. This “underproduction” also constitutes the unique dimension of a crisis since it is the exclusive measure of the economic loss resulting from said crisis. This being the case, it is clear that without the “multiplication” outlined above, any crisis would be impossible since one cannot imagine any primary implosion as large as the previous real crises of 1929 and before, i.e production decreases of 25 to 30% of GDP.

The capitalist system is in this respect the contrary of all other known or conceivable modes of production. In all the other ones, production is done in function of the resources available; consumption then happens in function of the volume of effective production and according to a given distribution model. The limiting factor thus being represented by resources, under-use of the means of production is inconceivable and an eventual primary diminution of resources could not trigger any secondary loss nor any cumulative process. The system reacts in this case by intensifying the use of its remaining resources, in turn reducing the primary loss itself to a minimum. The only thing that could happen in this case is a scarcity crisis but even there the term “crisis” would be an abuse of language. In the capitalist system, on the other hand, nobody can produce anything if they can not count on a preliminary market opportunity i.e pre- existing purchasing power. However, since no purchasing power can exist without prior corresponding production, the system finds itself fundamentally in contradiction with its own conditions of existence.

In all other systems, consumption is an increasing function of production, accumulation -therefore investment- being a decreasing function of unproductive consumption. Far from blocking the mechanism of reproduction, a lack of effective demand would maximize surplus, and as a result, growth. In the capitalist system, investment, that is to say production consumption, is a growing function of unproductive consumption. However, these two consumptions, productive and unproductive, are two components of a given aggregate: the global potential for production. As such, they are by their nature, inversely proportional to each other. It just so happens that those with the power of decision -entrepreneurs- are incapable of treating them any other way than directly proportional.

How is it possible then that, despite this fundamental contradiction, the system of market economy isn’t completely jammed now and forever? This is done because the effective production itself is constantly inferior to the potential production and thus can vary independently of the latter. It is these very variations, this “cycle” between a PLUS and a MINUS in the underutilization of the potential, this mobilization and demobilization of the reserve, which renders possible the simultaneous variation in the same directions of its two components. Thus assuring the cyclical equilibrium upon the very base of a structural disequilibrium.

The fact remains however that investment is counteracted by a permanent contradiction between its incentives and its means. When the incentives, which depend on the expansion of the market, are at their highest, the means, which depend on the rate of profit, are at their lowest, and vice versa. The system can overcome this contradiction only during the period of recovery, when the mobilization of the factor reserves permits the parallel increase of profits and the mass of wages without a proportional increase of their rates. Reaching full employment, and in view of the fact that the rate of capital accumulation is greater than the rate of demographic growth, extensive expanded reproduction (on the basis of an uneven distribution) comes to an end.

The system should then, to surmount this, either maintain expanding consumption without increasing employment, by changing the rate of remuneration of the factors, or it should shift to intensive expanded reproduction by separating the department of the means of production from those of consumer goods. Competition prevents the capitalists from doing one or the other, i.e. increasing wages or continuing to expand without increasing them, and crisis breaks out.

In all other systems, remunerations of direct producers constitute a simple revenue and nothing more. In the wage system, besides being a revenue for the workers, these remunerations are a cost for the employers, who find themselves also the sole deciders as to the allocation of factors. To maximize their profits they must minimize their costs, thus maintain the salaries at the lowest level possible. However, the profits are proportional to sales, and the sales are proportional to social revenue. As wages constitute the most important part of social revenue, the ex ante efforts of entrepreneurs to maximize their profits by the reduction or stagnation of wages leads ex post to the minimisation of both sales and profits.

Of course, consumer goods are not the exclusive object of profitable sales. The means of production can be just as well. The problem is, and this is crucial, that in the capitalist system the sale of the means of production can not serve as a substitute for the sale of consumer goods. They are an increasing function of sales of consumer goods.

The Coordinates of the Current Crisis

The contradiction that we have analyzed here- manifested at the level of the phenomenon of the fundamental contradiction between social production and private appropriation- if it explains crisis in general, it does not explain the onset of a specific crisis, even less so the current crisis, which is eminently atypical.

1- First and foremost, this crisis has not occurred according to the classic model above, at the moment when the economy hits the barrier of full-employment , but after 30 long years of non-crisis with employment hovering around this level alongside unprecedented and uninterrupted growth rates.

In fact, since the last war and until 1974, everything went along as if the system had transcended the “cycle” as if something pulled it out of the market/profit impasse within which it was struggling. This “something” was clearly the happy conjonction of effective union struggle and the contribution of substance that the terms of trade assured it from the periphery. The rise in real wages enlarged the market while the relative decrease in the price of imported inputs acted as an additional increase in physical productivity, preserving the rate of profit.

The Gordian Knot- low wages limiting investment opportunities on one hand and high wages truncating profits on the other- was cut by the inequality of foreign exchange which forced the poor to pay the superprofits of the rich. The capitalists of the core were able to increase their wages without cutting into their rate of profit, simply because the former is national and the latter is international. Herein lies the distinctive element of “consumer society”, which no one to my knowledge has bothered to actually define. If in fact this “consumer society” is anything more than just words, it can only be the situation in which good profits become compatible with flourishing markets.

It is after this long period of stable equilibrium and not at the end of a simple cyclical recovery that the current crisis- unlike all previous crises- came about.

2- All precedent crises accompanied a collapse of prices. In two years from 1929 to 1931, the most explanatory price index due to its universality, that of international commerce, had fallen by more than 25%. The current crisis, on the contrary, has accompanied a general increase in prices at unprecedented rates.

3- Third particularity: all precedent crises were birthed from a leading country and then propagated following a rhythm of maturation and at varying degrees of intensity in function of every country’s level of industrialization. The current crisis broke out everywhere at practically the same time and its unequal intensity from one country to the next is moreso in function of commercial balances rather than levels of economic development.

4- Finally, if what interests us is the real loss of social product and not the aesthetics of “grand equilibriums” and consequently if, as we have stated above, the under-utilization of productive potential both material and human is the only pertinent measure of the phenomen; the current crisis is of a different order of magnitude compared to past crises. To understand the difference, it suffices to recall that in 1933 the index of American production had fallen to half of that of 1929, while that of France had fallen to 75% of the same year. Unemployment in Germany was at 45%, in the United States it was at 35% of the active population. The sum of the profits of the 400 largest American companies in 1932 only represented 6% of their previous total sum in 1929, one third of American banks went bankrupt in 1931, the global production of steel in 1932 had dropped by 58% in comparison to 1929. To include the two situations, past and present, in the same general category of “crisis” is nothing more than a figure of speech.

This quantitative difference being, at least partially, the direct consequence of three specific, qualitative differences which are capable of differentiating the current crisis.

The Oil Factor

It turns out that what they call the oil “shock”, outside of its deflationary effects- a sine qua non condition of all crises of product realization in market economies- is also a generator of three developing syndromes of the current crisis.

- A rupture in the rules of the international game as well as a brutal diminution of the unilateral North-South transfer of resources;

- A general price increase accompanying the recession, which only an increase in an input as universal as energy can explain

- Finally, its simultaneous breakout across the world, which shows the presence of a common external factor, such as oil, as well as the modulation of its intensity in function of the commercial deficit of each country rather than the level of capital accumulation, which fits perfectly with the effects of the oil factor.

Nevertheless, as a primary trigger of this crisis and outside of its specificities, it is not that the adjustment of the price of oil acted as a “bill” to pay but rather, and as paradoxical as this may seem, it was that this same bill was not paid.

If oil was the product of such a country as Holland or the Scandinavian nations, the same price increase would not have provoked a crisis nor any major problem in the consumer countries. Of course there would have been a removal of real value charged to these countries, one that was strictly equal to the surcharge. This removal, however, would have been completely tolerable and without secondary effects.

For the oil imported by OECD countries, the surcharge rose to 80 billion dollars in 1974 for a GDP of around 4 trillion. During the second “shock” in 1980 it rose to 140 billion for a GDP of 7.6 trillion. Thus, in both cases around 2% of GDP. With the reserve of non employed factors, material and human, being superior to this percentage even during the period before the first “shock”, where there was already 3% of the active population unemployed and even more so during the second “shock” in 1980 when 10% of human potential and 20% of equipment was unused, the production of merchandise as a counterpart to the oil overcharge could have been provided at almost no social cost.

However as it turns out, the oil providers were not Holland or the Scandinavian nations but instead underdeveloped countries. Countries in which the internal revenues and thus, the final domestic consumption market were insufficient to absorb the additional imports that would have constituted the counterpart to the oil remboursement.

This deficiency would not have been a determining factor if these countries had planned economies capable of, like any integrated economic community, investing upstream independently of consumption downstream. On the contrary, the historically low level of final downstream consumption would have permitted them to accelerate the rate of upstream accumulation and thus, the rhythm of their growth. Only the composition in use-values of their imports would have changed. Their bill would have been “recovered” in full in real value, exactly like the other hypothetical case where the providers were Holland or Scandinavian nations. The tragedy was that these countries were both market economies and poor, that is to say: market economies without a market.

The crucial fact is that in the dynamic of a planned economy, it is the consumption of tomorrow that determines the investment of today, while in market economies it is the consumption of yesterday. The difference is that it is possible to project the consumption of tomorrow while that of yesterday must have already existed. In this case, yesterday’s consumption did not exist.

In short, everything happened as if the producer countries, after having been too poor to sell their oil at a remunerative price, were finally politically strong enough to impose an administered price but then found themselves the poor to be able to collect it. Both in 1974 and 1980, they were only able to “collect” about half of this price, leaving the other half to convert into financial assets in the buying countries.

Now, if these buying countries had been themselves planned economies, this partial non-payment- or deferral of payment- of the bill not only would not have bothered them but instead would have been welcome because it would have allowed them to avoid frictions and proceed to necessary readjustments by spreading out their supplementary productive efforts over time. However, in the fundamentally contradictory dynamic of market economies, such “savings” from their suppliers, far from being a boon, are a disaster. This is because the commercial balance deficits that reflect this “savings” generate a deflationist disequilibrium in a system which already carries a deflationary tendency. Beyond a critical threshold, this triggers the cumulative process of the crisis.

The Reaction of Oil-Importing Countries

The existing dirigisme in industrial countries- insufficient to reverse the dynamic but sufficient to produce additional distortions- aggravated the process. Distraught by these deficits (which they anticipated to be greater than they actually were), and in order to pass them off to one another, the oil importing countries took a series of measures in disorderly fashion which accelerated the chain reaction of deflation within the region.

In short, it was initially a matter of working a little more in order to pay a bill already reduced by half by the “savings” of the oil companies. In 1974, this represented, let us say, the equivalent of 2 million man-years[1]. The contradictions of capitalism made it so that instead of working more, working hours were five times less; instead of putting 2 million unemployed people to work, 10 million more workers were thrust into unemployment.

In terms of value, the OECD calculated the loss undergone during the second oil “shock” of 1980 at 7 and three-fourths% of the combined GDP of all industrial market economy countries, putting it at 7.606 trillion. The price during this second “shock” passed from an average of 15 dollars per barrel to 35 dollars, a surcharge of 20 dollars per barrel. The imports of OECD countries being 6.9 billion barrels per year puts the surcharge at 138 billion dollars, half of which was realized in imports and the other half in financial assets. It follows that a series of measures undertaken in the face of an autonomous deterioration in the price variable, to the order of 70 billion if we only count the part of the bill that was actually paid or 140 billion in total, resulted in a final loss of 590 billion according to the calculations of the OECD (7606×0.0775=590).

This “non-payment” of the oil bill turns out to be determinant, not only for the initial triggering of the crisis but also for its evolution. For there is not only the temporal coincidence of this triggering with the (singular) or the (plural) “shock/s”. There are also the ups and downs during its 10 year duration. If one traces the economic curve in the entirety of the OECD countries during this period, one would note that it fits perfectly with the equally turbulent oil “excesses”, themselves dependant on price fluctuations (in constant dollar terms) on one hand and on the development of the oil producing countries power to absorb foreign goods on the other.

Consequently, the mere observation of the facts should have been sufficient to accept- if only until proven otherwise- the causal link between the two phenomena and the long theoretical analysis above would have been redundant, however a curious conjunction of two intellectual inhibitions has created a powerful apriorism against the oil explanation.

First of all, there is a sort of guilt complex which creates a need for exoneration in third-worldist currents. It is as if the periphery would process its victory as poorly as the core processes its defeat. ( This may be perhaps something that gives meaning to the oft recycled notion of “dependence”, without which would have none. Ethical dependency. The periphery wouldn’t really be able to assume a position of strength, when it happens to be able to, whereas the “self-centeredness” of the developed countries would consist precisely in seeing itself as being able to do everything which makes- sometimes explicitly- the “interests of the West” a universal reference.)

The second factor is a kind of marxist congenital panic in the presence of any sort of hypothesis that seems to remove or depreciate the endogenous causes of the capitalist crisis.

I hope that the above formulation is of such a nature that it reassures those prone to either inhibition. The first group because what is being criticized is not the excessive character of the asking price, rather the incapacity of the sellers to fully appropriate it. The second group because one must really be sick of oneself to feel bad for being simply exempted from paying full price for the goods which one needs.

All of this does not signify that without oil there would have been no crisis in general. Capitalism carries its crisis within itself, like the storm cloud carries the rain. However, without oil the crisis would not have been the same and it would not have broken out at the same moment.

2. THE ANTI-CRISIS POLICIES AND THE SURPRISES OF STAGFLATION

At the end of this analysis on the nature and the process of the crisis, it becomes clear that the pivot point of our issue is the dialectic of inflation/deflation.

As we have just seen, the policies proclaimed at the outset in most countries (if not always implemented) were essentially inspired by the idea that the fight against inflation took precedence over everything else.

Let us say right away that apart from every other consideration, such unconditional priority is surprising in and of itself. In the January 9th, 1977 issue of Le Figaro Jean Denizet asked himself if it was not simply due to the fact that very few people alive today are old enough to have personally experienced Crisis, with a capital C. In fact, as shown above the parameters of capital C Crisis are so terrifying that it is difficult to understand how it is possible to take any risk in this direction.

One unemployed person, alone, represents a well defined loss without compensation for the community; one point more or less in a price index, after all, means only a transfer of wealth from one group of economique agents to another. As thorny as the difficulties of social and technical order due to price instability as a whole may be, their solution is certainly not easier with a reduced global social product than with a social product whose volume is maximized.

The Ambiguities of “Inflation”

At the base of the anti-inflation philosophy we find a fallacious assimilation between inflation and increase in prices. If we go back to the traditional definitions, inflation (without quotation marks) is an excess of purchasing power (and desire) in relation to the nominal value of global production- thus an excess of demand over supply- at a given price level. Raising this level, far from being the constituent element of disequilibrium, is actually the way out of it.

Is this playing with words? No! Simply because :

1- A price increase by the automatic reaction of the market which raises the nominative value of supply to the height of demand, is simply one of the means of re-equilibration. There exists another: make it so that supply equals demand, not by growing its value with the physical volume remaining unchanged, but by the opposite: the growth of its volume with the price remaining unchanged.

2- Even if we accept that all inflation tends to lead to price increases, the inverse is not true. All price increases are not necessarily caused by inflation. They could be due to a structural increase of costs, coming either from a modification of the technical conditions of production or a variation in the rate of factor remuneration.

It is this latter case that we improperly refer to as “cost-push inflation” to distinguish it from “demand-pull inflation”. This is inappropriate because it is not a question of two separate types of inflation but rather of inflation proper on one hand and an increase in prices on the other, which not only has nothing to do with inflation but also- and this is important- can perfectly well accommodate its opposite: deflation. Such is the case of oil which creates at the same time an increase in prices by its impact on the costs of production and at the same time causes deflation by its effect on trade balances.

This is what gives meaning to the term “stagflation”. The first component: stagnation, being indisputably a synonym for deflation, if we were to take the second component literally we would have a simple contradiction in terms: inflation despite deflation! However, if we replace the second component by “price increase”, we obtain something perfectly conceivable: price increase despite deflation.

The Price of Factors

Is the growth in the cost of inputs- oil and eventually other primary materials- the sole cause of structural (non inflationary) price increase? No! There is also the possibility of an exogenous variation of remunerations of certain factors, notably labor power, in the framework of an inconvertible monetary system.

Why this last condition? Because, if money is a commodity with an intrinsic value and is charged with its own production costs, all prices are relative and the growth of the remuneration of one factor can in no way lead to an increase in the general price level. A notion which in this case would be empty of meaning. Such a growth is necessarily compensated by a corresponding diminution of the remuneration of one or multiple other factors.

Also, on the hypothesis of the existence of a commodity-numeraire and a perfect convertibility: Ricardo, Marx and all those who, explicitly or implicitly, accepted the exogenous determination of wages have demonstrated that a general variation of their rates only affected relative prices. At the social level, it is counterbalanced by an inverse variation in the rate of profit.

These demonstrations no longer hold when the gold (or silver) standard is abolished and all prices, labor power included, are nominal and expressed in terms of absolutely inconvertible paper money, floating without limits in relation to other money. This is to say when money becomes a simple accounting unit.

In this case, entrepreneurs can easily incorporate raises in wages into their cost of production all while maintaining their habitual “mark-up”. The two variables- wages and profit- both become independent.

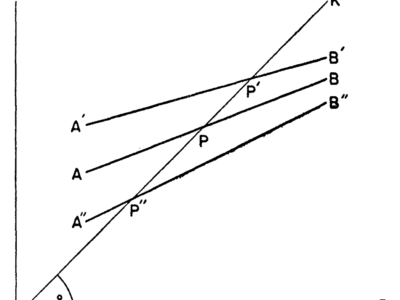

The difference between the two cases can be illustrated in using Sraffa’s paradigm:

(Aapa + Bapb + … + Kapk) (1 + r) + Law = A. pa

(Abpa + Bbpb + … + Kbpk) (1 + r) + Lbw = B. pb

‘ ‘ ‘ ‘

‘ ‘ ‘ ‘

‘ ‘ ‘ ‘

(Akpa + Bkpb + … + Kkpk) (1 + r) + Lkw = B. pk

If we were to assume the existence of a true standard and a total convertibility of money, we must take a commodity (k) as a commodity-numeraire. We will then have pk=1 which will only leave us (k-1) price to determine. In this case, all prices “p” will be expressed in terms of k which signifies that all prices are relative prices and that a general price “level” has no meaning.

Our variables being the (k-1) price ratios as well as a single “w” and a single “r”, we have only one degree of liberty. As soon as w is given, our system becomes perfectly determined. Since “r” is endogenously fixed, there exists no possibility for a general price increase. Any variation of w would result in a variation of r.

Things change radically if the monetary standard is “produced” outside of the system with no link to the production costs of k commodities. The prices expressed in terms of such a currency become absolute prices and the notion of their general level acquires a well defined meaning. We have then (k+2) variables (k price plus one r and one w), which gives us two degrees of freedom. It is no longer just w but r as well that must be given to us. This signifies, in clear language, that nothing forbids entrepreneurs from adding to their cost whatever margin that they wish.

In other terms: in the current monetary system (such as it developed after the transformation of the international gold standard into a more or less pure dollar standard) employers have the possibility to recuperate on prices and thus cancel in real terms ex-post the wage increases that they were obligated to provide in nominal terms ex-ante. It is in this sense that wages can be today considered as an autonomous factor of “inflation” or more strictly speaking: a general price increase.

We can express the same thing in another manner. An increase in the absolute value of goods can only signify a drop in the relative value of one sole good among them: money. When the latter is a real good (gold for example), for such a drop to happen (after a general increase in the quantity of currency distributed to workers) the organic composition of capital in the mines must be superior to the average for other branches of production and this superiority is commensurate with the increase in the rate of wages. There is no reason to assume such a singular combination. It would follow in this case that the capitalists have no way to withdraw from their workers in real terms what they have given them in nominal terms. However, when the workers receive dollars or paper francs, there is no predetermined proportion tying these things to the content of the average person’s shopping cart. The capitalists thus possess, at least in certain socio-politico conditions, the possibility to fix this proportion themselves by manipulating their selling prices.

In this case, as we could expect, the workers resisted the attempt to make them pay the oil “bill”. Trapped between the decrease in profitability and the rigidity of nominal wages, the system climbed out of the impasse on the back of price increases. The system thus relatively preserved profitability by disconnecting real wages from nominal wages. It is floating money that opened this door.

In addition to wages, within the context of an inconvertible monetary system all other factors whose prices are fixed exogenously (rent, interest, taxes, etc.) are susceptible to creating a general price increase. As in the case of wages, this price increase (improperly called “inflation”) has nothing to do with inflation stricto sensu and can very well be compatible and coexist with its opposite. It is this latter combination- with its opposite- which precisely constitutes “stagflation”.

In contrast, “true inflation” (Keynes) or demand-pull inflation cannot, by definition, exist in today’s conditions of underemployment. It is an extremely rare phenomenon in the capitalist mode of production which, except in very exceptional circumstances (war, blockades, etc.) is endemically deflationary.

The Contradictions of “Austerity”

We directly see the peril that restrictive supply measures can represent at a moment where, despite the increase in prices, effective demand is not only not in surplus but is particularly deficient as a result of the recession.

In a certain manner, austerity plans strive to bring relief to the two components of “stagflation”. Reducing “inflation” (still presumed to be the demand kind) by tamping down the consumable part of revenue all while stimulating investment by direct and incidental incentives in order to avoid depression.

It is cartesian logic. The less we consume, the more we save and invest. Investment and consumption are the two competing uses of a given aggregate: the social product. The trouble is that the system is anything but cartesian. It is afflicted by a fundamental contradiction between the power and the desire to invest. If the former effectively varies as an inverse function of the final consumption, the latter is coextensive with it. In these conditions, trying to stimulate or even simply maintain investment at a moment where final consumption is stagnating or in decline is as utopique as squaring a circle, no matter the direct measure of encouragement employed. This is the unrealized secular dream of capitalism: maximize accumulation without raising wages.

There exists another interesting link between the two components of stagflation.

The very existence of the latter component (“inflation” or price increases without quote marks) stops the former (stagnation) from evolving into depression and crisis.

The reason for this is that, in spite of the sales slump, the anticipation of an increase in prices to come incites entrepreneurs to dip into their savings and invest out of fear of losing more by keeping monetary assets than by maintaining their production activity.

Therein lies the important point. If we analyze the minor current recession, we cannot find one well defined particularity within it that ensures it will not degenerate into one of these cyclical pre war hurricanes, except that contrary to what happened in the past, today when all other incentives to buy have disappeared, one remains: the fear that the more purchase is delayed, the higher the price will be.

The priority accorded to the struggle against the increase in prices over the fight for full employment is thus inacceptable both socially and in terms of the performance of the economic machine itself. However, this is not all. Because it is absurd even within its own logique.

In effect, the scope of the distinction between “inflation” of costs and inflation (without quote marks) of the demand goes much further than the struggle against the increase in prices. It reaches the question of knowing if the ultimate determinant of the equilibrium prices is the market or production. Whatever the response, when it comes to a pure market economy, the social reality today has deprived the market of this role if only because the price of the most important production factor, labor power, is no longer part of the agenda. In fact the instruments of any plan of austerity themselves (credit restrictions, taxes, etc.) deprive the market of all determining force on the other factors.

Now, regardless of the doctrine, the state of demand could only influence the equilibrium prices of final goods if the latter could, in turn, influence the prices of their factors. It is therefore absurd to try to modify the level of demand with the idea of modifying the prices of final goods, when our own deliberate action consists in fixing the prices of factors before those of final goods.

If, as our analysis tends to show, the rise in prices is structural and is due to the conditions of production (including factor wages), the illogicality of deflationary measures is immediately apparent. Not only are they naturally inoperable as a means of reducing inflation, but they are likely to have effects contrary to their own purpose. In fact, some of their provisions destined to tamp down demand, such as increases in taxes or interest rates, have as an effect (involuntarily) to inflate costs and as a consequence selling prices themselves.

This is why the distinction between real inflation and simple price increases that we have insisted so much upon is not a theoretic subtlety but a substantial point. It is not about simply distinguishing the two parallel causes of the same phenomenon: the demand-factors and the cost-factors of inflation. It is important to realize that in a situation where there is absolutely no surplus but rather a failure of demand (as the first part of “stagflation” indicaties) combatting imaginary demand-factors often leads to real disastrous effects on costs and finally on prices.

Non Proportional Costs

What prevents the “perverse” effects of deflationary measures from being seen is the assumption of rising costs, which in the neoclassical camp rallies all the opinions, monetarists or other. If austerity doesn’t lower prices by tamping down demand, it will lower them by the diminution of the volume of production and, consequently, unitary costs.

On this point three different levels are confused: the level of quantitative variations in the entire branch of production, the level of economies of scale and the level of internal under-employment within enterprises.

Here it is a matter of the third level. Regardless of the direction of the non-proportionality of costs at the level of the entire branch of production, and ignoring economies of scale (that is to say, admitting that all enterprises have optimal dimensions and thus that all expansion of installations would lead to growth of unitary costs), the fact remains that from the moment where the already installed equipment are under-used, unitary costs are irrefutable decreasing.

The notion of fixed capital committed to a unit of production (of which the marginal use cost would be negligible, quasi-negligible or in any case inferior to the average cost not only for the company but for the entrepreneur himself) is impossible for neoclassical partisans, Their reasoning is based upon of a sort of universal “leasing”. As if, the factors being infinitely divisible, every morning the entrepreneur would buy exactly the necessary quantities for the days projected production: a certain number of man-days, a quantity of hours of a temporary secretary, a fraction of a building, machines, vehicles or the use of all of this. This would work out to where, once the evening arrives, he would be left with nothing but a stock of merchandise which he could then sell to restart the operation the next day at a varying scale depending on the conjecture of the moment. In these conditions, it is clear that the neo-classicals are correct. The more the sales, the greater the quantities of factors demanded and bought by entrepreneurs and consequently, on the margins, the lower their quality and the higher their price. And vice-versa.

However in reality, things do not happen in this way. The means of production may be divisible and mobile before their acquisition however once most of them, especially fixed capital, have been incorporated into a company they are immobilized. The financial cost is thus indivisible and independent from their being put to work. If we add to this the increased proportion of “white-collar workers” in the modern economies who are more or less immovable as well as the rigidity of certain other expenses, we obtain a “dead center” so elevated that the smallest drop in production would provoke a significant worsening of unitary costs.

The Internal Inadequacy of Deflationist Measures

Let’s go even further. Let’s admit for a second that the increase in prices is of an inflationary nature. The different austerity plans, founded upon traditional “quantitativist” tenants, would still fail to achieve their goal in a world which is no longer traditional.

The principal distortion comes from unemployment benefits which permit unemployed workers to maintain their consumption level without producing. Furthermore, when the living standard is as elevated as in the modern industrialized countries, the elasticity of the entirety of household consumption in relation to employment fluctuation is low. The owners of factors are attached to their habitual lifestyle. They seek to compensate for any lack of remuneration or any difference between remuneration and unemployment benefits by stopping to save or by borrowing.

We should celebrate this. This relative rigidity of consumption is (in modern capitalist economies) one of the most powerful antidotes against the ongoing process of reaction which before would have led directly to a major crisis. Today, a man who has been fired is nothing more than that. He is less likely than before to make another worker redundant by retiring from the market. On the other hand, a large part of any additional production can be carried out without a proportional creation of new purchasing power. The Phillips relationship is reversed. Far from increasing inflation, the recovery of employment offsets the excess demand, and far from reducing the monetary surplus, unemployment tends to increase it. For the supply of goods is reduced to the total unproduced value added, while demand is reduced only by the difference between wages and unemployment benefits

Of course, there are thresholds of discontinuity. Beyond a certain point, the internal contradiction of the process explodes. Neither unemployment benefits, nor savings or borrowing can finance an unemployment that would grow indefinitely. But this is precisely the danger of the operation, that even if demand has nothing to do with the rise in prices, it is always possible to break prices by continuously compressing demand. It is enough to go far enough in this direction to provoke liquidation sales. A major crisis is always lurking at the end of the process.

During the first stages of an austerity plan, when the that the results are contrary to expectations, i.e. when “inflation” worsens instead of calming down, there are two possible reactions:

- Realizing the inadequate character of this policy and stopping it

- Concluding that the applied restrictions are not drastic enough and reinforcing them

For all kinds of reasons, essentially linked to political credibility, governments largely prefer the second option. So, since the lack of growth is in itself a source of “inflation” because of falling costs, deflationary measures become a sort of self- justifying process by producing the very situation which makes them necessary.

Domestic Prices and Trade Balance

The need for a surplus or balanced trade balance is an argument of last resort of the advocates of austerity plans. According to this argument, an artificial boost to consumption would lead to a deficit in the external accounts without increasing national production, a) through prices, and b) through a disproportionate marginal propensity to consume abroad.

a) Elasticity – Price of Demand

The price argument is, in turn, based on two assumptions: (1) that a revival of consumption would lead to a worsening of “inflation”, (2) that, not only in volume but also in value, a country’s exports are a decreasing function (and its imports an

increasing one) of the level of domestic prices. We believe that we have shown the inanity of the former. If our analysis is correct, the latter is irrelevant. But assuming that (contrary to what we believe) the recovery would actually cause a rise in domestic prices, for this to lead to a deficit in our foreign trade, the second postulate must also be justified; that is to say, the price-elasticity of demand is greater than unity.

This is one of the most ineradicable ideas in Political Economy. And for good reason. It constitutes one of the three pillars, without which the entire edifice of neo-classicalism would crumble, the other two being rising costs (which we have also dealt with above) and the absence of “externalities” (external economies and diseconomies).

No systematic statistical study has ever supported this postulate. Even goods as standardized as primary materials show elasticity significantly lower than unity[2]. This is all the more true for the sophisticated products of the advanced industrial countries, whose specificity is considerably enhanced by the methods of production. Moreover, if we take into account the imported inputs, among those incorporated in our products, the “dead center” itself rises above unity. It follows that with an elasticity slightly higher than unity, as long as it does not exceed the level determined by the inputs, our trade balance, far from deteriorating as a result of a rise in our prices, would improve. If these phenomena are not simply erratic “perversions”, as they are sometimes considered to be, but the result of structural features of contemporary market economies, which are imperfectly competitive, it will be clear that certain policies recently applied in the OECD countries with a view to improving competitiveness on the international market are completely missing the point.

If we reduce the national differences of “inflation” to a common denominator, taking into account the devaluations and/or revaluations of the respective national currencies, we would find that the countries in surplus (Germany, Japan and Switzerland) are those whose prices, adjusted for currency variations, have risen the most over the last half decade. Whereas the countries in deficit, such as France and Italy, are precisely those whose prices, adjusted for currency variations, have risen the least.

This is what Jean Gabriel Thomas calls a disturbing paradox: “Countries that seek and obtain a price advantage in international competition do not benefit in terms of their trade balance, and the countries which suffer a price disadvantage are not in the least affected in their competitive position”[3]. The examples are numerous. The rise in the value of sterling by ± 20% against the franc between 1979 and 1980, when British domestic prices in pounds sterling rose by 18% compared with only 13.5% for franc prices, does not seem to have affected Britain’s exports of manufactured goods, which have even increased slightly.

Moreover, the dollar appreciated by 23% between 1980 and 1981. However, as price movements canceled out volume movements, the overall U.S. trade deficit did not change much. It is true that since then, and especially since the beginning of 1983, the deficit has increased significantly. Nevertheless, the assumption that the elasticity of demand is greater than unity has not been restored.

a) This increase is due solely to a rise in imports, reflecting the strong domestic economic recovery in the USA. On the other hand, US exports (far from falling as a result of the revaluation of the dollar like the postulate in question would infer) have been rising steadily since 1976 to the present day, although naturally at a lower rate than imports with the difference between the two variations constituting the deficit.

b) The persistent recession in Europe and the debt overhang in Latin America have had a specific negative effect on US exports.

c) If we disregard oil, the deficit itself disappears or becomes negligible. With regard to the overall deficit of $60.6 billion for 1983, non-oil trade shows a deficit of only $2 billion. d) The price elasticity curve of demand is not monotonic. Beyond a certain threshold, the possibility exists that it will reverse. If the price of a case of French champagne increases from 1000 to 1200 francs, exports will perhaps go from 10,000 cases to 9,000. A gain is recorded on both tables, the terms of trade and the trade balance. It is possible that, if this increase in price is continued indefinitely, there will come a time when external demand will collapse. The fact remains that below this threshold there is a considerable margin where (contrary to the neoclassical doctrine) currency reevaluations improve the trade balance of the countries that do it and devaluations accomplish the opposite.

The case of the United States in recent years is an extreme one. If one adds up domestic “inflation” and the dollar effect, foreign buyers must now pay about three times the 1979- 80 prices for American goods. If the US exports would have collapsed under these conditions, that would not be surprising. But, as we have just seen, this is not the case.

b) The Tendency to Import

It is here that the most gratuitous assertions are made. To hear the opponents of a “recovery plan” tell it, national production (independently of prices and for technical reasons, so to speak) would not be able to benefit from the distributed purchasing power which would be spent entirely or almost entirely on additional imports.

How and why industries with excess capacity in relation to their order backlogs, wholesalers, and retailers overstocked as a result of insufficient sales would not be able to meet the additional demand created by the recovery as easily and promptly as their foreign homologues is a question that the author of this paper has never had the chance to find an answer to in any of the relevant speeches.

That would still be fine if it were a special case of a specific country. But the same argument is used in all countries at the same time. So according to this logic, if the recovery were to take place in France, the Regie Renault, reputedly unable to capture additional French demand, would be perfectly capable to satisfy the additional demand from Germany, if the recovery was also taking place in Germany, while at the same time Volkswagen would be able to win new French customers, if the recovery was also taking place in France, but would be unable to serve its own compatriots if, by some chance, the recovery were to take place only in Germany and not in France.

All this seems to me to be beyond the average person’s comprehension. On the supply side, a certain effort to sell is deployed on the same market by both categories of suppliers, national and foreign. It is difficult to see why the national suppliers, who had a certain share of this market in times of full employment and easy sales, would relax their effort and let this share decrease in times of underemployment and poor sales.

On the demand side, in each country there exists an average propensity to consume foreign goods. All things being equal, it is of the same order of magnitude as the ratio of importation/GDP. To be more concrete, let’s say that in France in every shopping cart of goods whether it’s that of the household or of a factory’s “intermediate consumption”, we find 77% french products and 23% foreign products. We are willing to admit that despite the overcapacity of our factories, the shopping carts will continue to contain the same proportion of foreign products even after the recovery. But is there any reason that the post-recovery shopping carts would contain more foreign products than the stagflation shopping carts? We cannot find any and, in fact, can find a thousand reasons that it would contain less. The marginal propensity to consume foreign goods can, at most, be equal to the average propensity.

Certainly this marginal propensity to import remains positive and even if, contrary to the theory being examined, the recovery does indeed benefit national production for the most part; the fact remains that a part of it, however small, will flow outside the country’s borders, creating a deficit in the external accounts. The settlement of this deficit thus poses a problem.

This is indeed the only grain of truth contained in the theory in question. But this is also where the fundamental contradiction of the economic system that we live in is revealed. To prevent whatever 25 or 23 or 8% of additional purchasing power found in Germany, France or the United States that could be distributed in the case of a recovery from fleeing abroad, national industry is deprived of the possibility to produce, by using unemployed factors and thus at a zero or quasi-zero social cost, riches equivalent to 75, 77, or 92% of this same purchasing power,and that’s without even taking into account multiplication effects of economic activity.

Naturally, the percentage of this overseas “waste” depends on the scope of each group and therefore on its degree of “openness” to the outside world. At the level of the OECD group, it is reduced to 5%. For a concerted recovery on this scale the risk of external imbalance would therefore be negligible.. However, so far opposing interests have prevented such a collaboration.

Could a particular country move forward in this direction, independently of others? We think that this could be possible upon two conditions: a) the negotiation of it’s recovery with its partners in order to maintain it’s foreign trade at the status quo ante, b) it must be ready to sacrifice one part of it’s monetary reserves and/or go into debt to cover a possible residual deficit in its trade balance for as long as it takes.

This would signify in simple language that the country in question would put the market in the hands of its partners. Either they follow the path of recovery or they intervene to prevent their own recovery from benefiting others. Would this be a violation of free trade? I don’t think so. It is universally admitted that protectionary measures to safeguard national markets become legitimate as soon as they are in response to unfair competition or social dumping. It is difficult to see how introducing or maintaining austerity while the other country revives its economy is different from introducing an import tax or subsidizing exports. The simple fact that the country in question is only seeking to maintain the status quo is sufficient to demonstrate the defensive character of its interventionary measures.

As for the possible small residual deficit after such an operation, it is really not clear what the “reserves” can be used for, if not to face such situations. On the other hand, if this deficit is to be covered, in whole or in part, by debt, the explicit consent of the suppliers is not even necessary, since, materially, there is no way to sell to another more than we buy from them without accepting ipso facto his credit money.

3. FORMAL RECOVERIES AND UNSPOKEN RECOVERIES

A curious consensus was recently constituted, englobing left wing economists, on the subject of the alleged failures of Keynesianism. We do not see these failures.

Two countries, Austria and Sweden, applied Keynesian policies in a deliberate and systematic manner. Sweden did not hesitate to go to the most extreme and perilous measure to support growth, namely financing business inventories. The result was that the unemployment rate in the two countries was some of the lowest globally at 4%[4].

Another country where large-scale Keynesian policies were implemented (this time more accidentally than intentionally), as paradoxical as it may seem, was the United States under Ronald Regan.

If we follow the highs and lows of the budgetary deficit in this country, we notice that it was reduced in 1979, increased in 1980, reduced again in 1981, and rose again in 1982 with a much stronger rhythm than before to arrive today at the phenomenal figure of 200 billion dollars. Economic activity responded to these variations like clockwork, according to Anatole Kaletsky. The GDP dropped in 1980, recovered in 1981, dropped again in 1982 and finally in 1983 made its current vigorous recovery during which more that four million new jobs were created and, if we count the elongation of the daily working hours, the volume of applied productive work and thus the volume of wealth produced was increased by more that 7%.

At the same time- the ultimate refutation of monetarism- the “inflation” that had climbed up to 10.5% in 1980, dropped down to 4.25% in 1983.

Translated by Will Blanc.

- Translator’s note: Man-years as a concept is a unit of measurement that corresponds to the amount of work of one person during a year’s time. ↑

- UNCTAD II had recorded an elasticity of less than 0.5 for coffee, sugar, cocoa, lead, hard fibers, manganese ore and black pepper; between 0.5 and 1 for natural rubber, copper and oilseeds. ↑

- Le Figaro, 11-12.9.1976. ↑

- Already during the crisis of 1929, the social-democratic government of Sweden overcame it with a policy of domestic market recovery ↑