The articles below are working papers and, therefore, a project rather than a complete version. We are reproducing them here for general interest to provide deeper understanding of origins author’s concept of surplus drain.

Theoretical Origins of the Concept of Surplus Drain

The earliest conceptualizations of surplus drain derived from analyses of colonized areas and/or the decolonization process. In the late 18th century, Edmund Burke complained about the damage to India caused by British economic drains, and Naoroji, the “father of India,”centered his appeal for justice on statistically calculate “economic drains” by England. Through taxes, export trade profits, repression of indigenous crafts, and over- priced imports, Naoroji argued, the colonial state effected a “unilateral transfer of social surplus or potential investible capital to Britain.” In 1896, the Indian National Congress officially adopted his “drain theory” as their political criticism of colonialism, subsequently undertaking activist efforts to slow the surplus drains (Hajela 2001). In subsequent decades of decolonization, socialist scholars, like Nkrumah, recognized the heavy contributions made by the Third World to the living standards of “imperialist Powers,” but they did not explore peripheral surplus drain as one of the causes of world inequality (Grundy 1963).

In the 1960s and 1970s, radical nonwestern scholars continued to emphasize surplus drain as a central factor in world polarization. Walter Rodney (1973: 230-1) argued that European monies invested in Africa were originally derived from colonies. “Because of the super-profits created by non-European peoples ever since slavery, the net flow was from colony to metropole.” Similarly, Egyptian economist Samir Amin (2001) indicted colonial surplus drains as the historical sources of African impoverishment.

A surplus could be extracted here from the labour of the peasants and from the wealth offered by nature without investments of modernisation. . . without genuinely paying for the labour. . . without even guaranteeing the maintenance of the natural conditions of reproduction of wealth.

Arrighi called attention to colonial expropriation of African lands and displacement of indigenous people as massive surplus drains that privileged colonizer economic agendas over peripheral development. Colonial investments may have “deepened capitalism,” but “reinvestable surpluses” were either exported or utilized for luxury consumption by local colonists (Arrighi and Saul 1973: 19-22, 195, 220).

None of these early decolonization scholars focused sharply on theorizing surplus drain, and the roots of this concept do not lie in the intellectual arenas that many critics delineate. Dependency scholars like Prebisch (1984) and Cardoso (1972) did not explore surplus drain as a cause of slow peripheral economic growth. Moreover, it is important to emphasize that the notion of peripheral surplus transfers stands in opposition to orthodox Marxism. Marx (1967) introduced the notion of primitive accumulation to pinpoint the source of assets needed for the transition to capitalism. Through his choice of terms, Marx contended that non-capitalist accumulation was not a continuing component of capitalist economies. While Marx referred in passing to “countries exploiting countries,” he never integrated surplus transfer into his formal theory of capital (Avineri 1968). Nor could he have done so without great difficulty, for that theory is a theory of competitive capital within a national system. Globally competitive prices for commodities, resources and wages are assumed for the purposes of his theory. Subsequently, classical Marxist theories of imperialism (Lenin 1960) introduced the concept of monopoly to explain over-accumulation of capital in the core, thus falling profits and the need for state action (imperialism) to provide locations for new investments and markets. The classical theories of imperialism were primarily theories about the nature of the core (fights among capitalists) rather than about the nature of the relationship between core and periphery.

Neo-Marxist Dependency Scholars

Scholars typically fail to pinpoint correctly the earliest Marxist thinker who conceptualized peripheral surplus drains. Paul Baran (1957: 188-217) emphasized that the rational investment of surplus is the only source of economic growth and accumulation. Through lengthy quantitative analysis, he concluded that transfers of surplus left little wealth in the periphery to be reinvested, leading to blockage of development. “One participant of the team specializes in starvation,” he insisted, “while the other assumes the white man’s burden of collecting the profits.” Moreover, “transfers of economic surplus” are the root causes of peripheral “backwardness.” Emmanuel (1972: 371-2) argued that the worldwide disparities among wage levels produces unequal exchange, the structural process through which capitalists “drain off part of the surplus available for accumulation.” In turn, those losses cause “uneven development itself, as a whole, by setting in motion of the mechanism of these block-forces.”

Foundational World-Systems Thinkers

Inspired by Baran, Frank (1969) invented surplus transfer theory in its strong form, but he was the only early dependency theorist who put surplus drain at the very heart of his theory. Frank’s concept of the development of underdevelopment is based on a theory of capital drain–the transfer to the metropolis of surplus generated in the satellites. The metropolis-satellite relationship acts as both a siphon, a mechanism that draining away part of the surplus, and as a block to productive investment . According to Frank, underdevelopment is purposefully constructed by core capitalists, and the primary mechanism is surplus drain.

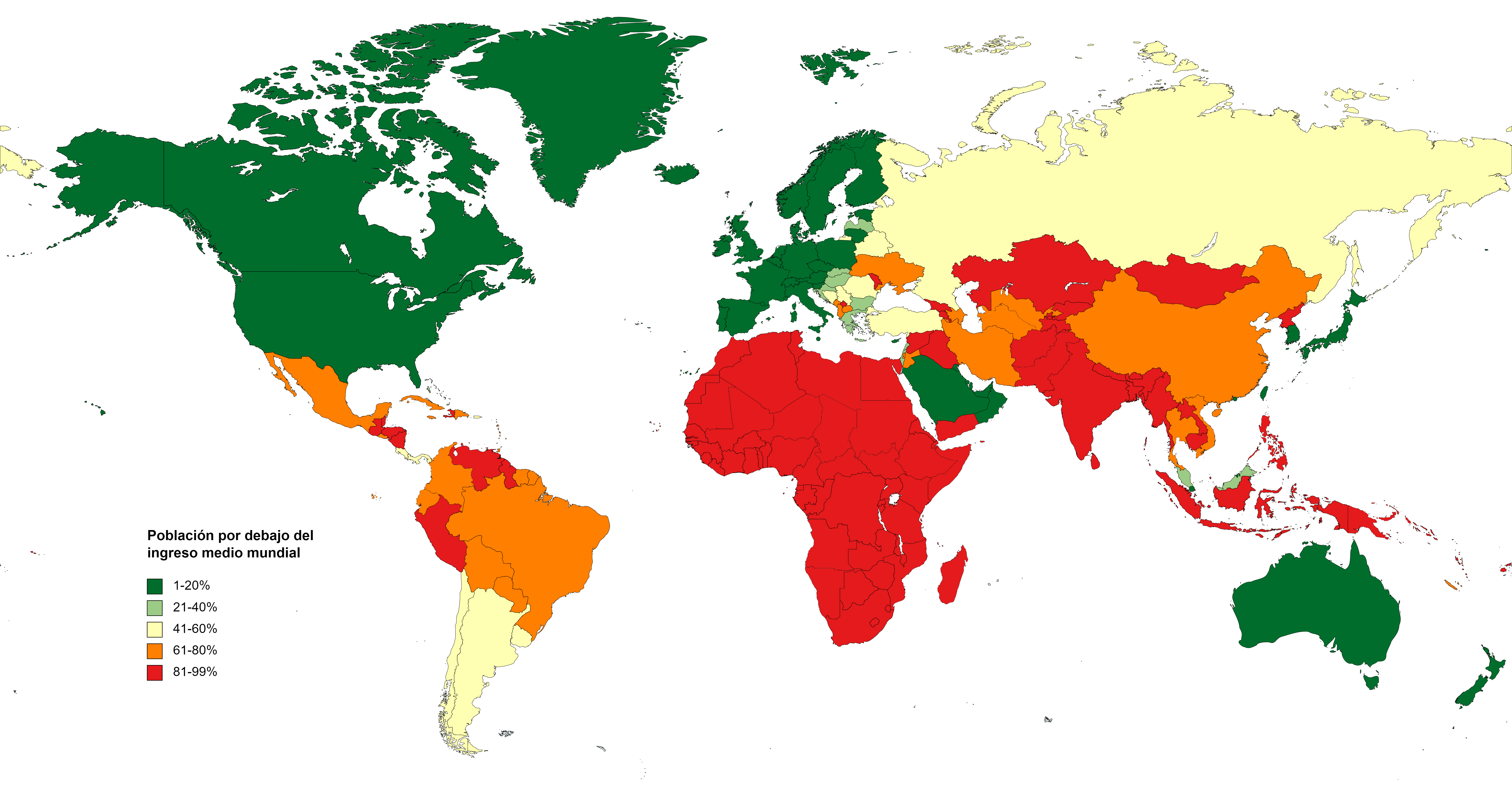

The presumed consequences of surplus transfer are twofold: significant benefits to the core and significant costs to the periphery. In the strong theoretical version, drains from the periphery are necessary to the rise of the core (Williams, 1944) and fully prevent the development of the periphery (Frank 1969). As used by world-systems foundational scholars, surplus drain is a revision of the Marxist theory of the expropriation of surplus value, that surplus embodied in labor. Wallerstein, Frank and Amin emphasized surplus drain as the driving force that caused the accumulation of wealth and dominance at the core and the impoverishment and dependency of the periphery and semiperiphery. Despite significant benefits to the core, the drain is a much larger proportion of the economy of the periphery than it is of the total profit wealth pool of the core. According to Amin (1974: 16, 106), 1960s surplus drains from peripheries ate up nearly one-fifth of their total economic wealth, amounting to nearly all the capital that might have been invested in expanded reproduction. The structured, long-term direction of this flow is from the periphery to the core. Both the core and the periphery are defined by this relationship, that is, defined by this exploitative relationship. Without this flow there is no core, no periphery, no world system as we know it. In contrast to many subsequent researchers, these foundational thinkers did not envision core and periphery as geographical or national categories but as relationships of surplus transfer. According to Frank (1969), the modern world-system is “a hierarchy of core-periphery complexes, in which surplus is being transferred.” In reality, the trimodal structure refers to “zones” that have core, seimperipheral or peripheral status. Consequently, the logic of surplus drain analysis specifies the existence and importance of internal peripheries . Surplus drain does indeed flow between countries, but it also occurs from a peripheral zone of one country to another country or between regions within the same country. For instance, coal flows from peripheralized Appalachia to fuel growth in other parts of the US (the same country) and to Japan (another core country).

References

- Amin, S. (1974) Accumulation on a World Scale: a Critique of the Theory of Underdevelopment, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2 vols.

- Arrighi, G. and J. Saul (1973) Essays on the Political Economy of Africa, New York: Modern Reader.

- Avineri, S., ed. (1968) Karl Marx on Colonialism and Modernization, New York: Doubleday.

- Baran, P. (1957) The Political Economy of Growth, New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Cardoso, F. (1972) “Industrialization, dependency and power in Latin America,” Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 17: 79-95.

- Dunaway, W. A. (2001) ‘The double register of history: situating the forgotten woman and her household in capitalist commodity chains,’ Journal of World-System Research, 7.

- Emmanuel, A. (1972) Unequal Exchange: a Study of the Imperialism of Trade, London: New Left Books.

- Frank, A. G. (1969) Latin America: Underdevelopment or Revolution? New York: Monthly Review Press.

- —– (1979) Dependent Accumulation and Underdevelopment, London: Macmillan Press.

- Hajela, P.D., ed. (2001) Economic Thought of Dadabhai Naoroji, New Delhi: Deep and Deep.

- Lenin, V. I. (1960) Imperialism: the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Marx, Karl (1967) Capital, New York: International Publishers, 2 vols.

- Mies, M., V. Bennholdt-Thomsen and C. von Werholf, eds. (1988) Women: The Last Colony, London: Zed Books.

- Petras, J. and H. Veltmeyer (2007) Multinationals on Trial: Foreign Investment Matters, Hampshire, UK: Ashgate.

- Prebisch, R. (1984) “Five stages in my thinking on development.” Pioneers in Development, ed. G. Meier and D. Seers, New York: World Bank, 175-91

- Rodney, W. (1973) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, London: Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications.

- Wackernagel, M. et. al. (2002) “Tracking the ecological overshoot of the human economy.” Proceedings of the National Science Academy, 99 (14).

- Wallerstein, I. (1974) The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press.

- —– (1983) Historical Capitalism. London: Verso.

- —– (1987) “the construction of Peoplehood: Racism, Nationalism,

Ethnicity.” Sociological Forum 2 (2): 373-87. - —– (1997a) “ecology and capitalist costs of production: no exit.” Keynote address at PEWS XXI. Univ. of California, Santa Cruz, Apr. 3-5. 1997]

- —– (1997b) “States? Sovereignty? The dilemmas of capitalists in an age of transition” Keynote address at conference on “State and Sovereignty in the World Economy,” University of California, Irvine, (Feb. 21-23).

Surplus Drain versus the Labor Theory of Value

World-systems writers rarely take a stand on the labor theory of value, although the concept of surplus value, implying acceptance of the labor theory of value, is often casually invoked (e.g., Wallerstein 1983). More orthodox Marxists take immediate notice of this absence, since the labor theory of value may be viewed as the very essence of orthodox Marxism, and attack world-systems analysis for its errors, Brenner (1977) still being the most commonly cited source after many attacks over all these years. The labor theory of value simply states that under capitalism waged labor is the source of all value. The hours of labor expended by workers in the production of commodities exceed the hours need to pay the costs of the reproduction of such labor. It is from these extra hours that the capitalist employer obtains surplus value, realized after the sale of the commodities. The surplus value can then be divided into its components – profit, rent and interest – and distributed accordingly. It is assumed that the underlying value of the other factors of production – land, resources, skill level, plant, machinery, and money – is based solely on previous inputs of labor (i.e., these factors represent “dead labor”). In a purely competitive system these costs of production vary little across space (they thus are “constant capital”), so the level of surplus value is determined solely by labor power (“variable capital”). [it is unclear whether Marx intended to produce a theory of how the underlying value of commodities is transformed into prices (the “transformation problem”) (cf. Baumol, 19__, for doubts about this), but he did recognize that once the short-term variability n demand and costs of production were taken into account that prices could vary from value (quite wildly) in the short run.]

It is my position that world-system analysts should take a distinct position on the labor theory of value, since not to do so is an insult to their own Marxian heritage and since not doing so contributes to the under-theorization of how the world-system works (its mechanisms and processes).

1. The labor theory of value is central to world-systems analysis in a qualitative sense (cf. Sweezy, 1942). The theory has always been (despite Marx’s denial) a moral theory of outrage against underpayment to the worker of the world for the blood, sweat and tears of their labor. This same moral assumption is basic to world-systems analysis. When deleted quite different perspectives emerge, engendering quite different understandings of how the world works .

2. The labor theory of value, in its standard form, assumes the relative equality of wages within and across capitalist modes of production spread throughout the world. [in Marx’s day, wages were indeed much more equal than today and approached the bare subsistence level] This assumption allows Marxists to ignore the problem of unequal exchange based on unequal wages identified by Emmanuel (1972) and Amin (19__). The orthodox Marxist attack on unequal exchange and world-systems analysis as “circulationist” tends to ignore the fact that, at least in Emmanuel’s and Amin’s hands, unequal exchange theory is based on a strict adherence to the idea that surplus value is produced only at the point of production. The latter try to apply the labor theory of value at a world level, something rarely even attempted by their critics.

3. Despite the key contributions of Emmanuel and Amin, world-systems analysis should explicitly reject the orthodox version of the labor theory of value. Most world-systems writers, no doubt, casually accept the assumption that all of the standard factors of production plus knowledge, organization, innovation and organization of markets may contribute to profits and surpluses. It is right that world-system analysis should be so mainstream on this issue, since this position encourages an interest in the multitude of sways that surpluses can be drained from one group or place to another. So Marxist critics world-systems analysis is based on the (dialectical) rejection (and expansion) of the concept “surplus value” in favor of a broader concept of “surplus”.

4. Classic Marxism, like neo-classical economics, is based on the assumption of nearly pure competitive capitalism. World-systems analysts rarely address the problem of imperfect competition (monopoly, oligopoly), but monopoly conditions are often casually assumed. I believe that world-systems thinkers should directly declare the assumption that a high degree of monopoly is the normal state of the system (cf. Wallerstein on Braudel, 19__) and indeed what drives it (hardly a neo-Smithian idea ). From bottom to top what drives all capitalists in their striving for accumulation is their search for some “degree of monopoly” (Kalecki, 19__), more so than their search maximal exploitation. The main task of any real practical capitalist is the destruction of the free market. Accumulation on a large scale always requires a degree of monopoly. It is the desire for market control that underlies its basic structure, the core-periphery relationship. Since surpluses and profits have many sources, capitalists can establish a degree of monopoly in a multitude of ways, one of the most important being a degree of control over labor markets.

5. Marxists often accuse world-systems analysis of the sin of ‘circulationism”, i.e., of paying insufficient attention to the realm of production, where all value is produced, and excessive attention to the spheres of trade and finance, where capitalists wheel and deal to obtain profits through redistribution of the surplus value that has already been produced but add no value. But even by the strictest Marxist view of surplus value, trade and finance are about the transfer of that surplus, close examination of these areas would seem a reasonable Marxist project. In addition, surplus value, again in the strictest sense, is often added, through the incorporation of labor power into an improved product at many steps in a commodity chain, from finance through the many steps in a production chain to the steps in a sales chain. It is true, of course, that fictitious value is added at many points in a value chain, fictitious value being an increase in price without an objective increase in utility. Such additions, by definition, entail some degree of monopoly. It is control of these points, often far removed from the last factory door, that is the source of large profits. Focus on control of these points is why capitalists “know the price of everything and value of nothing.” It is monopoly prices that drive the world-system.

6. Finally world-system analysis overturns the labor theory of value by expansion. In classic Marxism the proletariat (fully waged workers) is the definitional heart of capitalism. It is the class of the future. Slavery, sharecropping, tenancy, simple commodity production and other relations of production (mechanisms for the extraction of value from labor power) should have nearly disappeared. All of these forms of exploitation were essential to the growth of historical peripheral capitalism and remain so today. As intended, they all produce a surplus for the benefit of the exploiter. To the extent that the exploiter is using this labor power for the production of commodities, he performs the function of the capitalist (whatever he may be called or however he may think of himself) within the capitalist world-system.[could mention articulation of modes here] In addition, it is not the fully waged proletarian relationship that is preferred by the capitalist, but the semi-proletarian, who provides part the costs of reproduction by whatever means available (Wallerstein, 19__). This viewpoint stands in opposition to the Marxist to the Marxist view that the capitalist invents the proletariat exactly because full dependence on the wage for survival makes her more susceptible to control. Finally, world-systems analysis implies a recognition of the importance of unpaid (and nearly unpaid) labor in the reproduction of surplus-producing labor. Thus housewives, care-givers, household gardeners, and a vast array of service providers in the informal sector provide unpaid or underpaid labor power for the reproduction of proletarian labor power which can be sold as commodity (von Verlhof, 2007; Dunaway 2001).

7. Finally surplus drain analysis supercedes the labor theory of value by emphasizing that the drain of value goes much beyond the drain of labor power.