This is a draft of a part of the introduction for a forthcoming book with the working title, “The Long Transition Towards Socialism”.

Copenhagen January 2022.

My method is historical and dialectic materialism. However, it is a very broad term, covering many approaches reaching very different conclusions. Therefore, I need to be more specific on my specific edition of historical and dialectic materialism.

My method is not very philosophical; it is more a tool for analysis to develop strategy and thereby practice.

My method rests on three pillars. The first is the global perspective, which understands the world as a whole. The global perspective is grounded in both the history of capitalism as a world-system (Wallerstein) and the development towards a global value in this system (Amin). Taking the global perspective in analyzing might seem obvious, but it is not so. Most political strategies take the starting point in the local perspective, and then add the international perspective as a topping.

The second pillar is the “driver” of this process, the contradiction between the development of the productive forces and the mode of production. If we look at society as a whole, the fundamental contradiction is between the development of productive forces and the relations of production. The productive forces stand for technologies, practical and scientific knowledge, logistics, and management. The relations of production stand for the relations that humans enter into when using the productive forces; first and foremost, they concern property relations. The contradiction between the productive forces and the relations of production exists in all societies. It defines societies and their classes. In capitalism, it takes the form of the contradiction between the social character of production and the private ownership of the means of production; or, as Engels puts it in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific: “the contradiction between social production and capitalist appropriation.”[1] This refers to the fact that, on the one hand, production creates the basis of our lives and develops society with the help of an extensive division of labor between workers as well as between corporations, while, on the other hand, this is done based on the means of production being privately owned. This general contradiction has taken different forms in the history of capitalism, as the system attempts to find a way, to continue the development of the force of production, within the capitalist mode of production.

This leads us to the third pillar, “the principal contradiction” (Mao). If the development of global capitalism is one process, then this process has a principal contradiction. The principal contradiction determinate the outcome of local contradiction, but are at the same time modified by them. In this inter-action, the principal contradiction changes over time. The concept of principal contradiction takes us from the general level toward the specific level. It is a tool for developing strategy and practice.

Let us look at these three assumptions in detail.

The global perspective

First, I want to emphasize the use of the global perspective, the understanding of the world-system, as a multiplicity of cultures and political systems integrated into an extensive division of labor within a single world economy. Capitalism was born in a long process from 1500-1900, by colonialism giving rise to the development of capitalism in Europe.[2] Wallerstein has describes this process in detailed historical and political terms in his four-volume work: The Modern World System.[3] Wallerstein argued that capitalism is a historical system that has gradually built northwest Europe and North America as the core, other countries as semi-periphery, and most of the world as periphery. The process of colonialism connected and polarized the world into an imperial center and its exploited periphery, at the same time. The arrangement was necessary for the continued accumulation of capital. The extra surplus value generated by the exploitation of low-wage labor located in the periphery secured the profit rate; however, the realization of the profit was dependent on an ever-expanding market mainly located in the center.

Wallerstein’s theoretical framework originates from the “dependency theory” which was a response to the “development theory” in 1950ties, according to which the underdevelopment countries in the Third World had to develop in the path of the USA and Europe. A row of scholars turned this around and claimed that Europe has developed by the plunder and exploitation of the Third World. André Gunder Frank’s The Development of Underdevelopment (1966), Giovanni Arrighi’s The Political Economy of Rhodesia (1968), Samir Amin’s L’accumulation à l’échelle Mondiale, (1970), and Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1974) are examples of discussions within and between radicals of Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s.

Amin underlined that “transfers of value” (Amin 1970: 14) occur from so-called underdeveloped countries to so-called developed countries and these are the essence of capitalist accumulation on a world scale. Amin argued that Marx’s bourgeoisie and proletariat could be mapped to nations of the globe rather than merely as classes within nation-states. The generation of capitalism is not just enclosure. It is also the appropriation of wealth from the colonies.

Samir Amin was central in sparking world-systems analysis but also extended it into the political economy by describing the creation of global value.[4] The worldwide law of value operates through a truncated market that integrates goods and capital globally, but not the labor force and hence not the wage.

In today’s neoliberal capitalism, there is a global market for capital and commodities with globalized production chains linking labor-power in the North and South together. Furthermore, with the industrialization of the Global South over the last decades, the level of technology and management regimes are also becoming increasingly similar on a global level. The value of a commodity is no longer based on varied and isolated national conditions. The value is based on global conditions, and as such, labor-power has a globalized value. As Samir Amin explained:

“My major contribution concerns the passage from the law of value to the law of globalized value, based on the hierarchical structuring—itself globalized—of the price of labor-power around its value … this globalized value constitutes the basis for imperialist rent.” [5]

The seaport worker who loads containers in Shanghai creates as much value as the port worker in Rotterdam who unloads them, assuming that the work is of the same intensity and uses the same technology. The price of labor-power—the wage—varies due to the different histories, social relations, and political conditions, and the limited mobility of labor, as Samir Amin noted:

“Capitalism is not the United States and Germany, with India and Ethiopia “only halfway” capitalist. Capitalism is the United States and India, Germany, and Ethiopia, taken together. This means that labor-power has but a single value, that which is associated with the level of development of the productive forces taken globally. In answer to the polemical argument that had been put against him—how can one compare the value of an hour of work in the Congo to that of a labor-hour in the United States?—Arghiri Emmanuel wrote: just as one compares the value of an hour’s work by a New York hairdresser to that of an hour’s labor by a worker in Detroit. You have to be consistent. You cannot invoke “inescapable” globalization when it suits you and refuse to consider it when you find it troublesome! However, though there exists but one sole value of labor-power on the scale of globalized capitalism, that labor-power is nonetheless recompensed at very different rates.” [6]

The combination of globalized value and low wages in the South is the basis for the extraction of super-surplus-value, which generates super-profits for capital and relatively low commodity prices relative to Northern wage levels. The difference between the value of labor and its price, therefore, corresponds to a transfer of value from the South to both capital and labor in the North.[7]

Therefore, my global perspective is founded on the historical development of the world-system and the prevalence of globalized value in capitalism.

Productive forces and the mode of production

However, what is the driver of the development of capitalism? What is the contradiction that forces it to move ahead and constantly expand and change appearance? The conventional Marxist answer is the class struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. However, this answer has to be qualified.

Change depends on not only the wish, will, and organizational strength of the struggling classes – the subjective conditions. It also depends on the contradiction within the mode of production – the objective conditions. Marx and Engels write in The Communist Manifesto:[8]

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles…. Oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now ludden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large or in the common ruin of the contending classes.”

However, class struggle is just a manifestation of an underlying contradiction. What Marx and Engels discovered was the foundations on which class struggle takes place. With this, they laid the foundations of historical materialism.

If we look at society as a whole, the fundamental contradiction is between the development of productive forces and the relations of production. The productive forces stand for technologies, practical and scientific knowledge, logistics, and management. The relations of production stand for the relations that humans enter into when using the productive forces; first and foremost, they concern property relations. The contradiction between the productive forces and the relations of production exists in all societies. It defines societies and their classes. In capitalism, it takes the form of the contradiction between the social character of production and the private ownership of the means of production; or, as Engels puts it in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific: “the contradiction between social production and capitalist appropriation.”[9] This refers to the fact that, on the one hand, production creates the basis of our lives and develops society with the help of an extensive division of labor between workers as well as between corporations, while, on the other hand, this is done based on the means of production being privately owned.

Concerning class, the contradiction of productive forces versus relations of production are expressed in the contradiction proletariat versus capital. The state of this contradiction determines when class struggle takes on a revolutionary form. This happens when the development of the productive forces is in direct conflict with the existing property relations. Marx formulated this as follows: [10]

“At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or – this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms – with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces, these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.”

However, it is important to underline what Marx writes in the next sentence:[11]

No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient

have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older

ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework

of the old society.

I the last two hundred years there have been several severe crises in capitalism, creating local national attempts to develop socialism within the surrounding dominant capitalist world-system. However, capitalism has shown an extraordinary ability to roll back these attempts and to adjust, to incorporate criticism, and to find new escape routes out of the problems. The capitalist mode of production has developed the productive forces at a speed and to an extent never seen before in history. Creating growth in the earth’s population from 0.9 billion in 1800, 1.65 billion in 1900, and 7.8 billion in 2020. Fueled on fossil energy and constant innovations of new teleology, capitalism has developed an enormous variety and amount of products for sale with profit. However, also hunger and misery for the huge part of the world population who cannot afford to buy the goods they need. The contradiction in the system is coursing wars and the development of weapons of mass destruction, able to destroy humanity. Finally, the capitalist mode of production has polluted the environment and disturbed the ecological balance of the earth. To secure the continued development of the force of production in balance with humans’ needs and nature, a change in the mode of production is needed.

The historical development of capitalism is determined by the interaction between the economic laws of the accumulation of capital and class struggles entailed by the consequences of these laws. Certain conditions must be fulfilled to secure the accumulation of capital. The laws of accumulation can even be expressed in a mathematic formula – the rate of profit. However; “actually existing capitalism” is not a machine that functions exclusively through laws and rules of accumulation. Nor is it a system in balance and harmony. Quite the opposite: it is characterized by the constant struggle between the different aspects of its contradictions. For capitalism to function, it must constantly seek a specific historical form that allows it to secure profits and continue to accumulate capital. This form is determined by the class struggle. The economic laws create class struggles, which affect these laws; struggles that thereby develop the productive forces and modify the relations of production. This happens not only on the national level but also in the world system of states.

The class struggle on the national level shapes the economy and policy of the state, which is part of world-system of national states. The states interact and compete to secure their development. The national class struggle affects the world-system, which in turn affects the national class struggle.

The contradiction between the development of the productive forces and the mode of production had to find different historical forms of existence, in which capital accumulation could continue. In the 19th century wealth and raw materials were sucked from the colonial periphery into the center to develop industrial capitalism and the imperial mode of living. In the first half of the 20th century, it led to inter-imperialist wars over the succession of the British Empire. In the second part of the 20th century, new forms of imperialist relations had to be developed to maintain the profit rate, introducing massive outsourcing of industrial production to the periphery to take advantage of the low wage level. China has become the “factory of the world”, changing the balance of power in the world system.

The dialectical process between the economic laws of capitalism, their political and social consequences, and the related class struggles, is the force that drives the development of capitalism; a development that is not linear, but takes devious roads and is characterized by ruptures. During certain periods, the economic and political system appears relatively stable. Even when revolutionary movements try hard to change it, they keep their balance. However, the system will always be affected by revolutionary efforts; it does not remain the same afterward. During other periods, the system finds it selves in a crisis. It is no longer able to keep its balance and become unstable. At which point revolutionary efforts take on special significance and revolutionaries turn into butterflies who flaps with wings can cause a storm.

The division of the world system into different political entities means that the transformation of capitalism into a new mode of production will require many revolutions and can be subject to reversal as we have seen. The transition will continue to be characterized by class struggle on the national level and by the interstate conflict between pro-capitalist and pro-socialist states. The transformation from one mode of production to another is a long process. Capitalism first took shape over several hundred years, from the Italian city-states of the fifteenth century to the industrial revolution in England 400 years later. The transformation from capitalism to socialism will be a long process as well. There have been devious roads and blind ends. However, at this point in history, it seems that capitalism is running out of humans and nature to exploit.

The principal contradiction[12]

In the third pillar in my method, I move from the abstract and general to the specific and concrete. When analyzing a specific revolution as the Russian or Chinese is not enough to know the general contradictions in capitalism. When we study a particular society, it is necessary to consider its concrete contradictions, both their development and their relationship to other contradictions in the world-system.

Take a general statement such as: “Revolution is the result of the contradiction between the productive forces and the relations of production.” History shows that the development of this contradiction does not follow a straight path. If it did, revolutions would only occur in the most developed capitalist countries. If we look at history, we see that the path to revolution twists and turns. The major revolutions of the twentieth century did not occur in developed capitalist countries but in the periphery of the world system. The revolution in Russia and China and the numerous revolution in The Third World were the results of complex interactions between the particular contradictions inside the countries and the principal contradiction in the world system at the time.

If we have a capitalist world-system in the historical sense of Immanuel Wallerstein and the economic sense of Samir Amin. If we consider the world-system as one process, then at any given point in time, this process has a principal contradiction emerging from contradictions in the capitalist mode of production, and which drives its development forward.

The principal contradiction affects all national regional and local contradictions decisively. Like other contradictions, the principal contradiction changes during the course of history. The interaction between the principal contradiction and other contradictions is not one-sided. Particular national and local contradictions affect the principal contradiction. The feet back affects the struggle between the aspects in the principal contradiction and can change the direction of its development.

Mao says about the principal contradiction: [13]

“If in any process there are a number of contradictions, one of them must be the principal contradiction playing the leading and decisive role, while the rest occupy a secondary and subordinate position. Therefore, in studying any complex process in which there are two or more contradictions, we must devote every effort to finding its principal contradiction. Once this principal contradiction is grasped, all problems can be readily solved.”

The expression “readily solved” should be taken with a grain of salt, not least when talking about social problems and revolution in a country the size of China. What Mao means when he says “readily,” is that you have a reliable guide for further analysis once you have identified the principal contradiction. In other words, the critical problem in defining useful strategies, policies, means of propaganda, and military efforts are solved.

To identify the principal contradiction at a certain point in history, we must consider more than the general, abstract contradictions. Contradictions such as “productive forces vs. relations of production,” “proletariat vs. bourgeoisie,” and “imperialism vs. anti-imperialism” usually do not cause much controversy among Marxists. Disagreements begin when we move from the general to specific contradictions. When we need to identify the most important contradiction, at a given time and place, the contradiction with the highest revolutionary potential. Note that Mao speaks of “finding” the principal contradiction in the quote above. This cannot be done by theoretical speculation. Contradictions are concrete phenomena, they reveal themselves in economic developments in political action and popular movements.

We cannot understand the developments in a particular country without considering how the global and national contradictions interact. All this might sound self-evident and trivial. However, to study the world and develop strategies from a global perspective and the principal contradiction is anything but easy or common. Many analyses and proposed strategies are developed from the local perspective and neglect the global perspective and its principal contradiction influence on the situation.

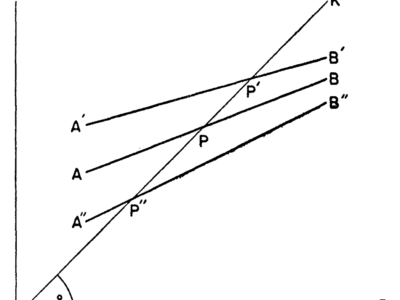

As I emphasize the global perspective and the principal contradiction, it is important to underline the dialectic. The world-level theory and universal trends consist of all the particularities. It is through the particular and local we can act. We need to see how the principal contradiction is created and formed by the multitude of particularities and how the principal contradiction determine the outcome of particular contradictions

This is not only a theoretical issue. The grand theory of the global perspective without the dialectic understanding of the relation to the peculiar is of no practical use. It may give you some academic pleasure of “understanding how the world works” and a platform from which to voice how unjust and unequal the world is, and it needs to be changed. However, “grand theory” alone offers no viable path toward an effective theory or praxis.

The meaning of seeing things as a whole and interconnected lies in the ensuing capacity to act in line with reality thus understood. The ultimate purpose in identifying the principal contradiction is to intervene in it. It is the conscious capacity of seeing the world system as a process and of understanding the direction and the eventual goal of that process. We cannot create contradictions, but we can influence the aspects of existing ones so that the contradictions move in a way that serves our interests. Identifying the principal contradiction tells us where to start.

To sum up. In the following analysis of the historical transitions process from capitalism towards socialism, I will examine how the general contradiction: productive forces versus relation of productions, manifests itself in the specific revolutionary process on the national level. Moreover, how do these national and regional contradictions interact with the changing principal contradiction on the global level. Dialectics analyze the world as an interconnected, contradictory, and changing totality. Change is an important notion.

Historical changes happen in qualitative leaps. The productive forces change constantly and with the power relations between classes. Eventually, this leads to tensions that shatter the framework of the old society and make way for a new one. However, there is no historically guaranteed outcome either.[14] No law makes socialism the historical stage that necessarily follows capitalism.

- ? Frederick Engels (1882), Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, chapter 3.” In: Marx/Engels Selected Works, Volume 3, page 95-151. Progress Publishers, Moscow 1970. marxists.org. ↑

- ? Lauesen, Torkil (2018) The Global Perspective. Page 29-94. Kersplebedeb. Montreal ↑

- ? Wallerstein, Immanuel (1974) The Modern World System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World Economy in the Sixteenth Century. Academic Press. New York. ↑

- ? “The world-wide law of value” (Amin 1991: 352-353). ↑

- ?. Amin, Samir (2010) The Law of Worldwide Value. Page 11. Monthly Review. New York. ↑

- ?. Amin, Samir (2010) The Law of Worldwide Value. Page 84. New York: Monthly Review Press. ↑

- ? I am aware that elements of the cost of reproducing labor power are cheaper in the Global South than in the North—for instance, food and certain services. Others are more expensive, such as education and healthcare. Some elements are difficult to compare, such as housing. A simple flat in a slum is cheaper than an apartment in a European city. However, a flat that is up to European standards, with hot water, heating, or air conditioning, is often more expensive in the Global South than in the North. Yet concerning most consumer products, there is a tendency towards the formation of one global market price. ↑

- ? Marx, K and Engels, F (1848), The Communist Manifest. Selected Works, Volume I, p. 33. Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977. Online: marxist.org ↑

- ? Frederick Engels (1882), Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, chapter 3.” In: Marx/Engels Selected Works, Volume 3, page 95-151. Progress Publishers, Moscow 1970. marxists.org. ↑

- ? Karl Marx, (1859), A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Preface. Progress Publishers, Moscow 1977. Online: marxists.org ↑

- ? Marx, Karl (1859), A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Preface. Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977. Online: marxist.org ↑

- ? Lauesen, Tokil (2020) The Principal Contradiction. Kersplebedeb. Montreal. ↑

- ? Mao Tsetung (1937), On Contradiction. Part IV.” In: Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Volume I, p. 332. Peking: 1969. Foreign Languages Press. marxists.org ↑

- ? Frederick Engels (1892), “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Introduction: History (the role of Religion) in the English middleclass.” In: Marx/Engels Selected Works, Volume 3, pp. 95–151. Moscow 1970. Progress Publishers. marxists.org ↑