1. First of all, thank you for the interview. We hope the Turkish anti-imperialist audience will be able to learn from the past and current experiences you can share with us from the perspective of a long-term activist from, what’s especially important, a country which belongs to the Global North. Living in an industrialised Scandinavian country, how did you turn towards revolutionary activism and anti-imperialist struggle? What were the main theoretical influences on you at that time?

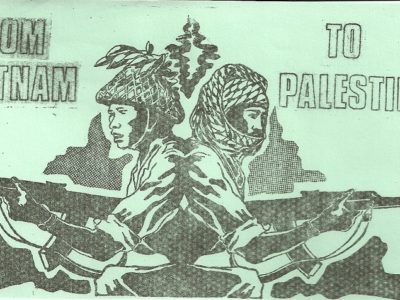

I was mobilized in the late 60s by the resistance against the Vietnam War, like so many others of my generation. In 1969, I bought my first political book. Fittingly, it was War Crimes in Vietnam by the philosopher Bertrand Russell. Recently I glanced and found the following passage underlined:

“To some, the expression ‘US imperialism’ appears as a cliché because it is not part of their own experience. We in the West are the beneficiaries of imperialism. The spoils of exploitation are the means of our corruption.”

These words, which obviously made an impression on me at the time, combined with a sentiment of outrage at US napalm bombs and the hope of justice for the people of Vietnam. It probably also combined with a guilty conscience, since I lived such a comfortable life while people in the Third World did not. It is characteristic for anti-imperialism in the Global North that is it something you can choose to engage in and then leave it again when it does not interest you any more or is not compatible with your career.

In the late 60s, I was introduced to the “Communist Working Circle,” a small organization based in Copenhagen. They were Marxist-Leninist-Maoist but with a twist. CWC had updated Lenin’s “parasite state theory” in terms of the modern social democratic welfare state. This corresponded to my everyday experiences. It explained that there was a direct connection between the wealth in our part of the world and the poverty elsewhere. The connection was imperialism. The parasite state theory also explained why the working classes in our part of the world were not interested in revolution but only in changes to the ruling system that would grant them a bigger share of imperialist plunder. Consequently, CWC developed an anti-imperialist and internationalist praxis. When I became member of CWC my individual, uncoordinated, and emotional political approach gave way to an organized and strategic one.

I went on study trips to the Third World and gathered resources to support Third World liberation movements, legally as well as illegally. Third World liberation movements were no longer abstract political entities but now consisted of real-life people and comrades who I felt accountable to. We wanted to be a little wheel in a big machine fighting for a different world order.

Our emotions, experiences, and actions led to constant questioning of our politics and ourselves. Theory was very important to us. Our practice was always informed by theoretical, strategic, and tactical reflections. Emotion, theory, organization, practice — everything was connected: emotions were the driving force, theory provided guidance, organization brought structure, and practice gave concrete results.

2. The 1970’s and 1980’s were periods of widespread revolutionary activity in the Western countries, especially within the framework of the autonomist movement and parliamentary opposition. How would you evaluate movements such as the Red Brigades in Italy, the RAF in Germany, Action Directe in France, the CCC in Belgium or November 17 in Greece? Do you think they made an important contribution to the struggle and brought about change? Do you think we could learn something from them in a theoretical and organisational sense? (That is, something that can be applied to the anti-imperialist struggle today either in the neo-colonies or in the imperialist countries.)

Well, the groups you mention are different: The Red Brigades had connections and influence in the working class, Greece’s November 17 operated in what I consider the semi-periphery, and so on. I am not so familiar with these groups. The only one we analyzed more carefully was the RAF and we developed quite a different praxis.

The praxis of CWC was to provide Third World liberation movements with direct material support. They were the foremost revolutionary force. However, at the same time, by this activity, we wanted to build and maintain an organization, and acquire practical and theoretical skills, which would be necessary in a future revolutionary situation in our own country.

We were in it for the long haul and therefore chose to work undercover, not underground. Had our illegal practice been openly political—with communiqués about expropriations and the like—we would have been chased down in no time. Our actions had to look like ordinary crimes. This made it possible for us to operate for almost twenty years.

The Red Army Faction in Germany attacked US army bases to support the anti-imperialist struggle in the Third World. In principle, there is of cause nothing wrong with that. Our goals were similar. However, their actions were openly politically motivated and intended to shake up imperialism’s hinterland, tear what they called the “democratic mask” off the German political system, and serve as an inspiration to the masses. However, the Red Army Faction were not “fish swimming in the sea.” They did not have mass support. The German working class did not have any sympathy for anti-imperialism or socialism. So the RAF were quickly forced into a defensive underground struggle, which they were destined to lose and which diverted them from anti-imperialist actions. We thought their strategy was based on a wrong analysis of the ’68 rebellion’s political depth and the possibilities of broad anti- imperialist resistance in Western Europe. This was not a dry prairie where you could spark a fire — to paraphrase Mao — but a damp meadow.

3. From today’s perspective, while looking back at your activities in the 1980’s and supporting the anti-imperialist struggle in the developing world, how would you assess the achievements and failures? That is, what lessons can you draw from that struggle that would be important for today’s activists to bear in mind?

Our anti-imperialist strategy was based on supporting national liberation struggles in the Third World. We believed that they would establish socialism in the periphery, end imperialism, and cause a crisis in the imperialist countries that would rekindle revolutionary unrest in the First World. If I ask myself today, forty years later, how much of this has proven accurate, the answer is clear: not much.

It seems obvious that we were too naive and optimistic. But this is a simplistic interpretation of the times. First, revolution was on the agenda in the 1970s. Millions of people in the Third World were willing to fight and die for it. The US was defeated in Vietnam. There were reasons to be optimistic. Therefore, I object to our being painted as “revolutionary romantics.” The real romantics were those who thought that the working masses of the imperialist countries would rise in rebellion. Yet, it is true that decolonization and the success of several national liberation movements brought about neither socialism nor an end to imperialism.

We were in close contact with the liberation movements we supported. Their socialist convictions were definitely genuine. In analyzing the legacy of the liberation struggles, it is too easy to simply focus on how power corrupts. There were other reasons for socialism not becoming a reality. Each struggle had its unique features, but I will focus on three that affected them all: the structure of the global economy; the question of power in a nation state; and the lack of socialist examples.

Concerning the global economy, the most important obstacle to the development of socialism in the newly independent countries was the rise of neoliberalism. The neoliberal doctrine was all about free trade and integration into the capitalist world system. The newly independent countries did not have the power to change these dynamics. Nor could they simply increase wages and world market prices for coffee, copper, and so on. They stood in competition with one another, forced into a race to the bottom. Detaching themselves from the world market—delinking—risked throwing their national economies into ruin. They had not been able to lay the economic foundations for the countries they were now governing. They had inherited the economic structures established by their former colonial oppressors—these were not designed to serve their interests but those of the colonizers. They were stuck with monocultures and industries limited to processing a few raw materials. Any major transformation of the economy demanded capital. But where was capital to come from if not from selling the only products they had on the only market that was available, that is, the capitalist world market controlled by the old colonial powers and their economic allies? No matter their aspirations, the economies of the newly independent countries were determined by capitalist realities.

The poor countries were still drained of value through unequal exchange. The national liberation of individual countries did not change the dynamics of the global market. Theorists of imperialism have given much thought to the question of socialism in the newly independent nations. They agree on the obstacles: the world market, unequal exchange, the ongoing divide between center and periphery, etc. They do not necessarily agree on the medicine. Amin suggested the strategy of delinking, while others have demanded a New International Economic Order and increased South–South cooperation.

The second problem was the limited power of the national state. The history of the socialist movement is, in many respects, a history of national movements operating within the boundaries of modern nation states. The idea of revolution has mainly revolved around seizing state power and the control of governmental institutions. The term “internationalism” indicates that, on the global level too, nation states have been regarded as the main political actors. On the one hand, this focus made national revolutions possible. On the other hand, it stood in the way of socialism because socialism is difficult to establish in isolation and under outside pressure. Most of the newly independent countries of the Global South found themselves in such circumstances.

Global capitalism limits the autonomy of the individual nation state. Anticolonial movements were faced with this once they gained (partial or total) state power. This made it often difficult, or impossible, to realize their original goals. Today, it is easy to say that this was inevitable and that the anticolonial movements should have known better. But they had little choice. Seizing state power was necessary in order to at least change the balance of international relations. The various attempts to strengthen the political position of the former colonies and newly independent nations show that, at the time, it seemed possible to collectively make a difference.

A third problem was the lack of positive real socialism.

The tensions between the individual nation state and the world system did not just affect the relationship between the newly independent nations and the imperialist countries, but also affected the state socialist camp. In the early years of the socialist movement, it was commonly understood that socialism could only be established globally. Lenin was convinced that the survival of the Russian Revolution depended on revolutions succeeding in Western Europe, especially Germany. When revolutions in Western Europe failed to materialize, he was deeply concerned. In March 1923, shortly before his death, he stated: “We are confronted with the question—shall we be able to hold on with our small and very small peasant production, and in our present state of ruin, until the West-European capitalist countries consummate their development towards socialism?” As we know, revolutions in Western Europe did not materialize. In the 1930s, the Soviet Union adopted the maxim of “socialism in one country.”

The revolution that had never come in the West came in the East. In 1949, the Communist Party of China proclaimed the People’s Republic of China. During the 1950s, the Soviet Union heavily supported China. This occurred at a time when the Soviet Union was still recovering from World War II and facing an increasingly hostile USA. However, the relationship between China and the Soviet Union was not perfect.

The reasons for the conflict were manifold. One was simply the question of who was the rightful leader of the international communist movement. There were also differences in the approach toward the USA. Due to economic and military pressure, and with the possibility of a nuclear war in mind, the Soviet Union had entered a period of “peaceful coexistence” with the West. One of the consequences was that the Soviets would no longer sponsor China’s nuclear program. In China, sentiments were very different. The Chinese had fought US troops from 1950 to 1953 in Korea, and the US protected the dissident Chinese Republic of Taiwan. This was not the only foreign policy issue where Moscow and Beijing didn’t see eye to eye. There were also ideological reasons for the dispute. Within the Communist Party of China, two factions stood increasingly in opposition to one another. Mao stood for the Party’s left wing, Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping for the right wing. Mao’s economic program, known as the Great Leap Forward, had not brought the hoped-for results, and the right wing used this to its advantage. For Mao, the right wing consisted of Soviet agents. Mao’s main ideological critique of the Soviet Union was that it denied that class struggle continued under socialism. The Soviet leadership claimed that class society had ended and that the state belonged to the people. In Mao’s view, a new bourgeoisie had risen to power in the Soviet Union. He feared the same was about to happen in China under the leadership of Liu Shaoqi. There was also concern over provoking the USA, given the possibility of a nuclear war. In a 1956 interview with the American journalist Anna Louise Strong, Mao famously described US imperialism as a “paper tiger,” stating: “In appearance it is very powerful but in reality it is nothing to be afraid of, it is a paper tiger. … Strategically, we must utterly despise US imperialism. Tactically, we must take it seriously.” Eventually, the conflict between the communist leaders of the Soviet Union and China reached a point where reconciliation no longer seemed possible. This caused a major split in the international socialist movement that had negative consequences for socialists everywhere.

The national interests of socialist states often weighed more heavily than international solidarity in the fight against imperialism. This contributed to the decline of the anti-imperialist movement at the end of the 1970s. But there were exceptions. The Cuban government under Fidel Castro supported numerous anti- imperialist struggles in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. The Palestinian organization PFLP also put international solidarity into practice. In their training facilities in Lebanon, they welcomed members of numerous liberation movements from the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. This made a big impression on us. It was one of the reasons why we saw true revolutionary potential in the worldwide collaboration among liberation movements.

None of this, however, could prevent the fading of socialist hopes in the 1980s. The capitalist world system and the modern nation state certainly played their part, but problems in the socialist camp itself cannot be denied. State socialism did not provide the example of a better world we had hoped for; both democratic structures and economic progress were lacking. We did not have examples of viable socialist societies. It is not enough to say, “Well, state socialism wasn’t real socialism. Let’s try again!” There were numerous genuine attempts to create socialism over a period that spanned almost a century. The fact that none of them delivered the goods requires serious reflection. It is not surprising that people lost faith in a socialist future.

But socialism did not fall out of favor with the masses of the Third World because the capitalist system was suddenly able to meet their needs. The global distribution of wealth is still unjust, leading to social unrest and violent conflict, but many of today’s resistance movements lack visions of freedom, equality, and solidarity. The disillusionment with socialist liberation movements has led many to embrace forms of right-wing anti-imperialism, often represented by religious fundamentalists who were originally trained and equipped by the imperialist powers as counterrevolutionary forces, as for example in Afghanistan, Iraq, or Syria. On the other end of the spectrum, we find the naive belief that liberalism and formal democracy would instantly turn the entire world into Europe. In the Middle East and North Africa, there once prevailed a socialist, pan-Arab vision that united people from Iraq to Morocco; today, political dissidents either demand an Islamic state or a parliamentary system and free markets.

There is a need for concrete visions of socialism; visions that are both attractive and attainable. There is also a need for strategies to get us there. Actually existing socialism—and, with it, the anti-imperialist movement of the 1970s and 80s—vanished with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The window of opportunity had been opened by the two global superpowers trying to neutralize one another; it was now closed. Material support for liberation movements was no longer forthcoming, and for the former colonies that had become independent countries, it was now more difficult than ever to pursue a socialist course. Neoliberal capitalism set the agenda and integrated the newly independent countries into the capitalist world market on its own terms. To delink and build self-reliant economies was a herculean task that the newly independent countries were unable to accomplish.

This also meant that they were constantly drained of resources that would have been vital to building strong national economies; they were destined to remain poor. Any attempt at implementing socialist policies despite the difficult circumstances was met with opposition from the US and, if necessary, simply crushed. The revolutionary movements of the twentieth century made huge sacrifices in their attempts to topple the dominant order. Still, they failed, being met with brute force as well as cunning strategies of cooptation.

It is important, however, to remember that each of these movements forced capitalism to adapt. Capitalism has gone through enormous changes in the past hundred years. The national liberation struggles did not lead to world revolution or even produce individual socialist nation states, but it would be wrong to say that they achieved nothing. They brought an end to colonialism in Africa and Asia. They brought an end to the apartheid regime of South Africa. Dictators in Latin America were toppled. The fate of the Palestinians entered the global consciousness.

What is the situation today? The former colonies have not been able to escape imperialism, despite independence. The ruling elites of the newly independent countries constitute—more or less willingly— a class of compradors. Workers and peasants have largely lost faith in socialism and now put their hopes in either Islamism or liberal democracy. This has extended the life of global capitalism. The crisis of 2007, however, was an early sign that it is nearing its end. The causes underlying the crisis went much deeper than irresponsible financial speculation, and they will not go away. The next thirty years will see many windows of opportunity for radical change. If the 1970s were characterized by too much optimism, then the present is characterized by too much pessimism.

4. Most of the revolutionary organisations around the world, not only in the developed countries but in general, have not evolved theoretically past the classics of Marxism-Leninism (or even Maoism) so that their analysis of the global political and economic relations did not catch up even with the theories of unequal exchange of the 60s, much less with the changing relations in the world today. Do you consider Arghiri Emmanuel’s analysis still valid for the analysis of the world today and as a guide to chart the strategy of the global anti-imperialist movement? If not, what do you see as an alternative?

Yes, for sure. Emmanuel’s main contribution was that within a classic Marxist value analysis he explained the value-transfer in international trade. Marx had plans to investigate foreign trade more closely in a fourth volume of Capital, but never got to write it. Emmanuel picked up this loose end. According to Emmanuel, the historical basis for unequal exchange was laid by colonialism between 1500 and 1800. The unequal relationship between center and periphery had been cemented by the 1880s. While only subsistence wages were being paid in the latter, wages were significantly higher in the former. According to the theory of unequal exchange, wages are key to assessing a country’s position in the imperialist order. With regard to their actual value, goods produced in the Global North are sold for a relatively high price, and goods produced in the Global South for a relatively low one. The notion of unequal exchange in trade between Global North and South is based on a Marxist understanding of value insofar as this trade implies value hidden in the low prices of goods produced by cheap labor.

What has happened since is that production itself has been globalized in the form of transnational production chains. As Emmanuel’s unequal exchange was a critique of Ricardo’s comparative cost, unequal exchange in Global Chains of Production is a critique of the mainstream theory of price formation, the so-called “smiley curve.”

In neoliberal economic theory, the formation of the market price, for example of a computer, is described as a chain, in which each step adds value to the product. The chain typically starts in the North, from where it heads South, before returning to the North and its consumers. A curve illustrating “value added” along this chain looks like a happy-face smiley. In the beginning, when financing, management, development, and design are handled in the North, there is much value added; then there is little value added when workers in the South, for low wages, actually produce the product; and, finally, there is again much “value added” when the product returns to the North and requires branding and marketing to be sold. “Hot air” is one of the few products whose production has not yet been outsourced to Asia. A characteristic feature of global chains of production is that they pass through very different labor markets. According to the happy smiley curve, the biggest part of the product’s “value” is created in the North – but it is the difference of wages along the chain of production that shapes the curve.

If we apply Marx’s conception of value, the curve looks different. If you draw a curve for value added during the production of a computer or a pair of sneakers following Marx’s theory, it will look like a sad-face smiley, the exact opposite of the curve drawn by neoliberal economists. This does not mean that their curve is “wrong.” It simply illustrates the creation of price, while the sad-face smiley illustrates the creation of value. The reason for labor in the Global South being much cheaper than labor in the Global North is not that labor in the South creates less value. The reason is that laborers in the South are more oppressed and exploited.

This is what Zak and I try to explain the article “Imperialism and the Transformation of Values into Prices.”

5. In the article “Imperialism and the Transformation of Values into Prices,” published in Monthly Review, that you co-authored with Zak Cope, you point out the issue of how the countries of the periphery (or Global South) got industrialised but still remain in the subordinate potion due to the technological dominance of the Global North. Do you think this shift also dictates a change in the anti-imperialist strategy either in the South or in the North?

The industrialization of the South was not introduced to create a more equal world. It was an escape route for capital out of the economic crises of the mid-70s. A way to maximize profit, which gave capitalism a new golden age from the end of the 70s until the financial crises in 2007. Nonetheless, it changes the dynamics of global capitalism. For the first time in the 500-year history of capitalism, a country of the periphery has risen to be the world’s leading industrial producer.

So in this new dynamic we have on the one hand a continuing transfer of value and thereby a tendency to polarization, and on the other hand we are witness to an hitherto unseen development of productive forces in the Global South, which has in many way turned the tables.

Until recently, it seemed hard to imagine that neoliberalism would come to an end. But the presidency of Donald Trump and the decline in US hegemony, Brexit, the erosion of the EU and the G-7, and the rise of right-wing populism have changed the political landscape drastically. The industrialization of the South begins to backfire and creates new political problems for capitalism in the South and the North.

Three decades of outsourcing and privatization eventually affected wages in the Global North. The initial victims of the crisis were the least flexible workers in industrial production. But soon part of the middle class felt the effects as well. In the US and Europe right-wing populist parties seized the opportunity with nostalgic appeals to an era of national sovereignty where none of the fatal consequences of neoliberalism could have ever occurred: the outsourcing of jobs, the deterioration of living standards, the dismantling of the welfare state, and the arrival of way too many foreigners.

This put a lot of pressure on the political system. When grievances are expressed within this system that the ruling parties have no answer to – for example, to establish control over the economy again – it, too, hits a crisis with no certain outcome. The traditional parties of all stripes – conservative as well as social democratic – are desperately looking for possibilities to bridge the gap between the demands of neoliberalism and the rise of nationalism. So far, they have not been very successful. The Brexit referendum and Donald Trump’s astonishing victory demonstrate just how deep the neoliberal crisis has become.

We must be clear on national right-wing populism: It does not challenge capitalism, but it throws capital into confusion. The global situation is complex and unstable. Economic power lies with globalized production and a financial sector whose legitimacy is under fire. The political order is threatened. The leadership of the Triad shows signs of disintegration as the recent G-7 meeting in Canada showed. Russia is eager to be a global player again, and China has become both an economic and a political heavyweight. Meanwhile, the new proletarians of the Global South become increasingly aware of their own power. The regimes of the region that proved unable to translate political independence into economic sovereignty have lost popular support and rely increasingly on authoritarian measures to stay in power.

While the anti-imperialism of the 70s focused on national liberation, anti-imperialism in the future will focus more on anti-capitalism.

6. Beyond any doubt the fall of the socialist bloc has dealt a death blow to many anti-imperialist movements. How do you see the global struggle from that perspective given there is no financial and political support for the liberation movements? What would be the strategy to link isolated anti-imperialist movements in the world and keep them going?

The decline of US hegemony, the erosion of the EU, the return of Russia as a global player, the rise of China, but also of India, Iran, Brazil and so on, all indicates that we are moving towards a multipolar world system, which can give anti-imperialist movements more room to maneuver.

7. Talking about the death of many movements, how do you evaluate the “peace processes” around the world such as that of the FARC where another socialist country, Cuba, acted as a mediator? Having in mind that many similar attempts ended up in either the demise of the movement or its ideological shift to opportunist positions, that is, their integration in the imperialist world order, do you think it will spell an end to the liberation struggle?

Yes, as mentioned above, I think we are moving from national liberation to “economic liberation” – anti-capitalism.

8. The global anti-imperialist movement is anything but homogeneous and there are heated debates about the issue of collaboration with the imperialism. For instance, in one of the current focal points of imperialist intervention, the Middle East, the Kurdish nationalist movement has placed itself under the US, allowing it to establish military bases on the territories under SDF control. There are many revolutionary organisations that support the Kurdish movement, and yet many others that criticise it for collaborating with imperialism. How do you see this cooperation? Does it strengthen the position of the imperialist powers in the Middle East or does it create an opportunity for the anti-imperialist forces to build an independent alternative to globalisation? What outcome should anti-imperialist activists expect and how do you think they should approach this issue?

The Kurds fighting in Turkey and Syria are certainly progressive forces. But they are not a major player in the region. They rely on allies, which implies great dangers. The big players in the region remain the imperialist powers, and they can easily turn their allies into pawns. To follow the logic that my enemy’s enemy is my friend might be inevitable under certain circumstances, but it is a dangerous game and it never delivers long-term results. At the same time, it is easy to insist on a primary correct political line from a safe distance; if you are active on the ground, things can look very different.

9. The previous question brings us to another important issue: given the increasing role of Russia in imperialist conflicts and interventions, do you consider Russia an imperialist country (for example, according to the theory of unequal exchange what would be the proper characterisation of Russia) or a country which is weakening global capitalism while introducing a multi-polar world? How should activists regard Russian politics and actions?

Russia is a national capitalist semi-peripheral country, which is trying to regain some of the global influence of the Soviet Union. Russia has returned as an important player in global politics, eager to push back US and EU influence in the former Soviet republics and regions with strong historical ties to the Soviet Union. Its involvement in the conflicts in the Ukraine and the Middle East attests to this. But even if Russia aims to establish a national economy independent of the US and the EU, it is largely dependent on an oligarchy of private monopolies, established under the first post-Soviet government led by Boris Yeltsin. The oligarchs have no interest whatsoever in socialism. The conflict between Russia and the US/EU alliance is a classic conflict between (actual or aspiring) imperialist powers. This inter-imperialist competition can give anti-imperialists some room for maneuver, but Russia is not an ally.

10. Although China is not intervening in political struggles as much as Russia, it’s heading towards becoming a growing economic and military imperialist power. What do you think about China’s development and its future contradictions with US and EU imperialism? Also, how do you evaluate China targeting Third World countries as a dominant power?

I think China’s role is far more complex than Russia’s. China’s integration into the global economy is a conscious national strategy controlled by the government. Faced with the neoliberal offensive after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Communist Party of China chose neither passive submission nor rigid opposition to the neoliberal project. The Chinese government wanted to catch up with the rich countries and restore China’s global might. In order to achieve this, the nationalist wing of the Party decided to copy the technology and management of the imperialist countries and enter the global market. At the same time, there are still factions within the Party committed to building socialism. This situation has led to the current form of Chinese state capitalism.

China was keen to avoid unconditional integration into global capitalism. The government defended its sovereign economic planning and forced global capital entering the country to adapt to it, not vice versa. China’s aim was to develop a strong and diversified industrial sector on the basis of joint ventures with transnational corporations. Conditions in China are, of course, unlike those in any other country of the Global South. Industrialization is controlled by the government. Certain regions are developed first according to a strategic plan. China has strong national banks and a strong national currency with increasing international importance. Agriculture has been modernized, and remains under strict government control. Land cannot be privately owned. Finally, the country is not engaging in an arms race to the detriment of the national economy, as happened with the Soviet Union. But questions remain. Can the influence of the transnational corporations be contained? Will China develop a strong national bourgeoisie that will seize power and turn China into a regular capitalist country? Will the appeal of consumer society be stronger than socialist convictions? Can state capitalism actually develop into socialism?

China is sometimes referred to as “sub-imperialist.” Those who use this category cite China’s investments in Africa, where it extracts raw materials and has become a player in the lucrative mining industry. But I think the term “sub-imperialist” blurs the fundamental differences that exist between these countries and the imperialist powers. China is looking for resources in Africa, but the net result is a massive value transfer to the Global North. Most of the imported raw materials are used by China’s export-oriented industries. What we see, therefore, is Northern consumption disguised as Chinese consumption. China’s policies in Africa (and elsewhere) certainly do have an exploitative character, and this would remain so even if China were to delink from Western imperialism. This will only be exacerbated if China continues to prioritize the comprador capitalist aspect of its economy over the national one. Some analysts suggest that China will replace the Triad as the world’s hegemonic capitalist power, thereby becoming the savior of capitalism.

The current Chinese model of capital accumulation is based on the exploitation of cheap labor. The source of cheap labor is about to run dry, however. The industrialization of China has led to the massive exploitation of the country’s natural resources and to enormous environmental problems. China’s industrial cities are plagued by pollution, not least because China is dependent on coal for about 75 percent of its energy consumption. Yet air pollution is only one of several ecological crises that China is facing. According to the International Finance Corporation, China is expected to have a water deficit of 25 percent in 2030 due to the constant increase in water usage by agriculture, industry, and the urban population. As a result of both climate change and the lack of water, China’s corn production risks falling by 18 percent by 2040. If China is not going to introduce fundamental reforms, then converging economic, political, social, and ecological crises promise to put enormous pressure on the regime. Currently, China’s capital accumulation relies on increasing exports to capitalist core countries. But is this possible in the long run?

China’s industrialization led to overproduction and unsustainable exploitation of natural resources and energy consumption. In times of economic recession—and not least in light of Trump’s “America First” policies—China’s export markets will shrink. One possible solution is to raise wages and strengthen the domestic market. The latter is something that the Chinese government is already trying to do; since the financial crisis of 2007, the Communist Party has passed a number of resolutions that indicate a shift from prioritizing exports to strengthening domestic consumption. But this inevitably implies higher wages, which raises concerns for both Chinese and transnational capital, for which low wages in China are essential. While China’s rise as a global economic power went hand in hand with the rise of neoliberalism, China’s long-term national interests are not identical with the long-term interests of global capital. China is trying to reshape international politics; it is challenging the hegemony of the Triad and wants to see a polycentric division of global power. The Chinese government increasingly represents the interests of the Global South in international debates. Its influence in Asia, Africa, and South America is growing; it invests heavily in infrastructure projects, sets up alternative development banks, and seeks to create a new kind of Bandung Alliance to counter the dominance of the Global North. To be credible, though, it will eventually have to abandon its pragmatic alliance with capitalism and develop an economic model that promises a true alternative to it.

11. As pointed out in “Unequal Exchange and the Prospects of Socialism” by the Communist Working Group (that is, as per Arghiri Emmanuel) the Western working class has no interest in global socialism given that they enjoy privileges of the current world order (also according to Johan Galtung’s “Structural Theory of Imperialism” where he points out the disharmony of interests between the working class of the center with the working class of the periphery), How can Western activists increase support for the movements in the countries of the periphery? Is there anything that can be done in the West to change the current balance of power?

Anti-imperialists in the West are a minority, but an important minority. The priority must be to support anti-imperialist forces in the Global South; forces that have a radical anticapitalist profile and a popular base. These can be revolutionary political organizations, labor movements, or the remnants of the national liberation struggles in Palestine, Kurdistan, Western Sahara, and elsewhere. We must support them materially, practically, and politically. Solidarity is action and it must be concrete. However it also includes analysis and contributions to the development of strategy.

Another important aspect is to make the imperialist hinterland unsafe. We must oppose political and military interventions in the Global South. We must also fight racism and demand citizenship for refugees and migrants. We must support the free movement of people across borders. Solidarity is not based on citizenship but on class.

Finally, we need to develop viable forms of organization, practical skills, knowledge and tactics for the struggles that lie ahead. We must think strategically – this means to think several years ahead, not just until the next election. But we must also be prepared for the repression we will face by an increasingly authoritarian state.

12. The Anti-Imperialist Front, based in Turkey but international in character, is trying to bring together anti-imperialist organisations around the world and coordinate common actions. How do you think the roles between the organisations belonging to South and the organisations belonging to North should be arranged?

As mention above, at the moment the South is on the frontline and the North is the “hinterland”. However, the coming years will be dramatic. Things can change quickly. There will be uprisings in response to severe economic depression. There will be widespread unrest because of ecological devastation. Moreover, there might be revolutionary struggles as a consequence of inter-imperialist wars. We are at a historical threshold. A new world order will emerge from brutal conflicts between progressive and reactionary forces. The stakes are high. Will the system self-destruct and take the whole world down with it? Will it revamp itself in the form of a global apartheid system? Will it be replaced by socialism?

We certainly need to coordinate our struggle both between South and South and between North and South.

13. Anti-imperialism itself is not a standalone ideology but rather a strategy of a variety of movements that has traditionally been dominated by the forces following the Marxist-Leninist tradition. With the inaction, opportunism or plain inability to adapt to the new circumstances, the dominance of ML forces is being challenged by various ideologies, very often nationalist or even religious in character. Do you think they are able to bring and drive the necessary change? What should activists do to make sure that anti-imperialism remains principled and uncompromising rather than being subordinate to the political interests and objectives of non-communist movements?

There have been many forms of anti-imperialism, often including reactionary ones. Historically speaking, American independence was anti-colonial and the Ian Smith regime in Rhodesia was anti-imperialist. Today there is a mix-up between anti-imperialism and anti-Americanism. In that way, Iran becomes seen as anti-imperialist. For me anti-imperialism is linked to anti-capitalism and vice versa. The two struggles are inseparable.

14. Finally, Turkey has long and ongoing tradition of militant anti-imperialist struggle. Do you have a message to Turkish anti-imperialist militants?

Well I think we have ground for optimism. Maybe we were too optimistic in the 70s, but I think there is too much pessimism today. The objective conditions for change are favorable. The capitalist system is in a structural crisis. The power of the US and the EU is declining. They are split and confused. In that situation activists become important, actions matter. The problem is that the subjective forces of revolution are weak; however, this is up to us to change. There is no reason to be pessimistic. Rather we need to start to organize and prepare for the dramatic changes to come.

Source: https://kesintisiz.org/interview-with-torkil-lauesen/