The most bittere fruits of my [book] “Unequal Exchange” were the negative conclusions regarding the international solidarity of workers. Of course, it is not just a question of noting that the manifestations of this solidarity are weakening in the world–an assertion that is, moreover, very debatable–but rather of knowing whether the objective basis of this solidarity has disappeared or whether it is nothing more than a passing wave of opportunism that prevents the peoples of the rich countries from becoming aware of their true long-term interests.

It was from this second position that the critique of my book began. It is neither denied nor minimized that economic imperialism has allowed certain social reforms within the large industrial countries. But they object that those “immediate” advantages that momentarily differentiate the workers of poor and rich countries are nothing compared to the common long-term gains that they will gain from the destruction of capitalist relations worldwide. The divergence of “short-term” interests is not an objective basis for breaking the international “solidarity” of the workers; rather, it is the objective basis of nationalist opportunism.

It seems to me that interspersing the word “opportunist” between a first and a last cause does not save anything from what it is intended to save. If the objective situation determines opportunism, which in turn determines the lack of international solidarity, we can eliminate the intermediate proposition and say that the objective situation determines the lack of solidarity.

Apparently, in the reasoning considered, “opportunism” consists precisely in the lack of awareness of the other objective basis, which is long-term interests. They argue that a world socialist revolution will increase production in all countries to such an extent that in the long run not only will differences between nations be erased, but also the obligation to compensate rich peoples for losses arising from the fact that the current distribution of world wealth has come to an end. Lack of awareness does not mean that this reality does not exist.

Of course! But neither does it assure us that it exists. If the awareness of a given reality is historically impossible or inoperative, we have a situation there that differs in no way from its opposite reality. Awareness is also part of reality. In other words, if today’s workers refuse to take the long term into account, perhaps it will happen that the long term is too far removed from the normal perspectives of human consciousness…. And this constitutes an objective obstacle to internationalism. Also, in the long run, we will all be dead.

From worker aristocracy to aristocratic nations

This is not the first time that international reality has led Marxists to heartbreaking dilemmas. In general, in the past, they came out of this uncomfortable position thanks to the concept of “worker aristocracy.” The “imperialist” gains could only corrupt a thin layer of the proletariat of the advanced countries; this layer constituted the social basis of opportunism. The great proletarian masses always had “nothing to lose and everything to gain”.

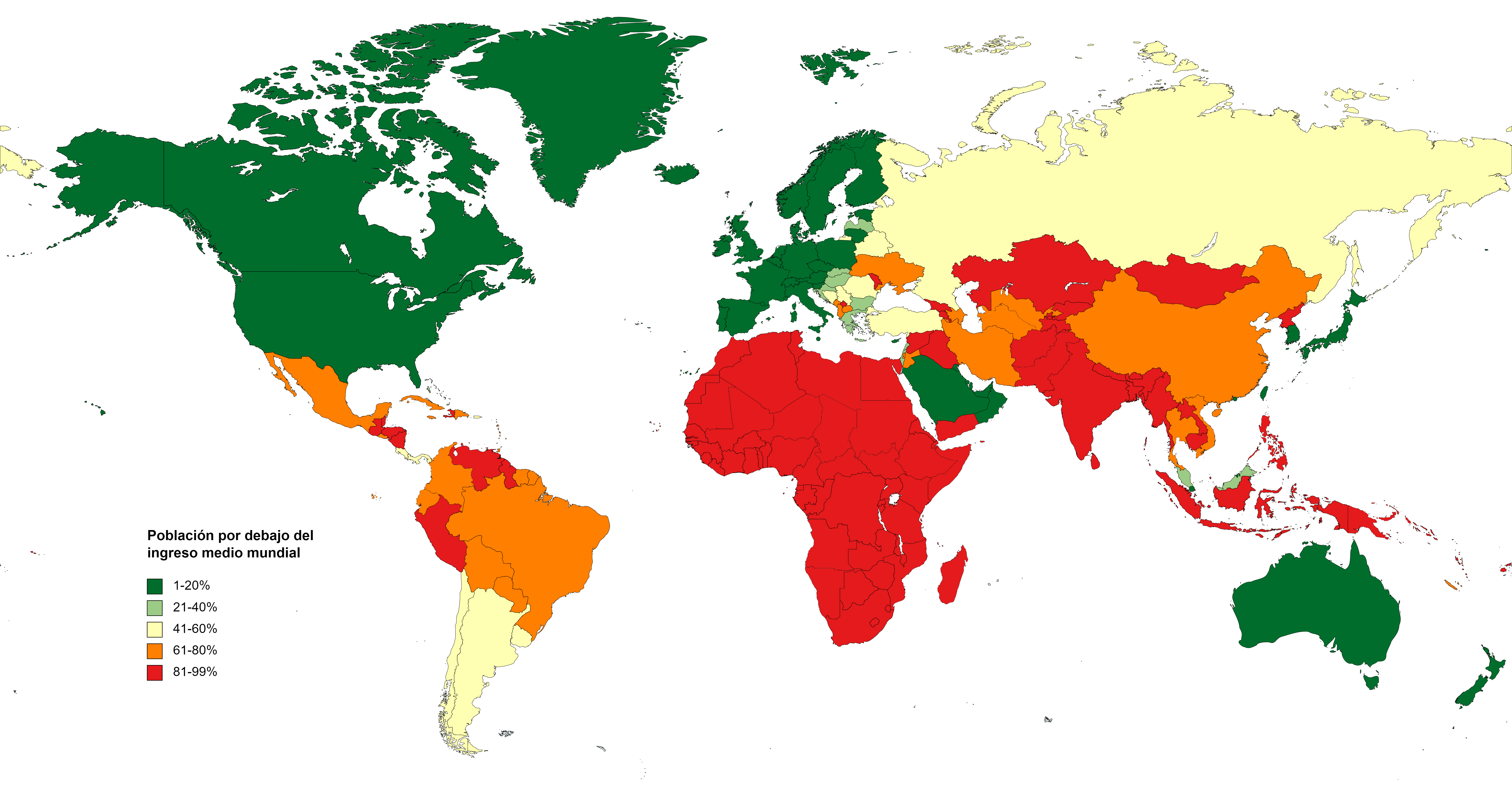

This simplistic and reassuring theory corresponded very well to a certain historical reality. In fact, the national bourgeoisies began to distribute with certain privileged layers of workers the cake of international exploitation. The difference in standard of living between a white collar and a worker was greater than that between workers in different countries. But in the second half of the 19th century things began to change. The trade union struggles in the large advanced countries led not only to a broadening of the distribution of the product of exploitation abroad among the classes but also to its redistribution among the different layers of the same class. With greater or lesser speed depending on the country, a situation arose in which the difference between the white collars and the workers of each rich country was minimal in comparison with the abyss that separated the workers of the advanced countries from those of the underdeveloped countries…. Unless it is regained at the international level, the category of workers aristocracy is perished.

This mutation did not cease to be reflected in the thinking of the classics of Marxism. In his last important text, before his death, Lenin expressed in these terms his deep disillusionment with the fate of the advanced countries: “Will we see… the day when the capitalist countries of Western Europe have reached their path to socialism? They will not arrive as we thought before… They will accede not through a natural ‘maturation’ of socialism, but at the price of the exploitation of certain states by others… The final outcome of our struggle depends on the fact that Russia, India, China, etc., make up the vast majority of the population of the globe. However much the internationalists then attacked the Stalinist theory of socialism in a single country, tens of years later, when revolutionary Marxism takes power over millions of men, it will never be “socialism-in-several-countries” but “several-socialisms-in-one-single-country”. Socialism became an internal affair. As such, it does not necessarily contradict exploitation and antagonisms between rich and poor nations.

Marx and Engels had already had their share of “lost illusions”. In the 1940s they expected the establishment of socialism and consequently the emancipation of the most backward nations in the most advanced countries, especially in England. To this is subordinated the national problem. The independence of Ireland went through the socialization of England. The revolution would go from the centre to the periphery. When England became immune to the revolutionary tornado of 1848; when chartism perished; when English capitalism overcame, without too much harm, the economic crises of 1857, 1864/66 and 1873 and continued its development by integrating the proletariat into it; when in 1870, 104,000 London workers signed a petition to the queen protesting against Glad-stone’s supposedly anti-imperialist policy, Marx and Engels looked to the periphery, to Poland and Russia to the East, Ireland and the United States to the West. “There is nothing to be done with the English workers,” Engels wrote in his letter to Marx of August 11, 1881, “so long as England’s monopoly subsists.

As soon as the distribution of the product of international exploitation (super-profit) becomes more and more important, if not preponderant in the dynamics of the class struggle within the same nation, this struggle ceases to be a real class struggle in the Marxist sense of the term and becomes a settling of scores between partners around the common booty. The national pact ceases to be questioned in its essence, and national loyalty transcends opposing interests on the one hand, and is fortified by international antagonisms on the other. National integration in the large industrial countries was possible at the price of the international disintegration of the proletariat.

Colonialism has produced both supersalaries and super-profits, but its long-term effect on the metropolises, whether desired or not, was to favour the proletarians more than the capitalists. Because of the tendency to equalize the rate of profit worldwide, the super-profits are only temporary. Supersalaries are automatically and eventually converted into normal wages, ending up constituting that “moral and historical element” of the value of the labor force, of which Marx spoke to us.

As I maintain in my book, when the relative importance of the exploitation that a working class suffers by the fact of its belonging to the proletariat, diminishes continuously in relation to that which it enjoys by its belonging to a privileged nation, there comes a moment in which the objective of the increase of the national income in absolute terms is superior to that which pursues the improvement of the part of each one. That is what the workers of the advanced countries have understood so well, that for half a century they have progressively become social-democratic, either by adhering to the existing parties of that tendency or by inculcating it in the communist parties themselves.

If capitalism could give each working family a home and a car, while raising above wages a surplus value that would ensure their extended reproduction without major crises, as it is in a position to do in the richest countries, certain Marxist theorems would need serious revision. But capitalism itself is not capable of such exploitation. It was only able to shift pauperization and unemployment from the national framework to the world framework. But this profoundly modifies the nature and constitution of the revolutionary fronts.[1]

Arghiri Emmanuel

- Rosa Luxemburg, op. cit., capítulo XVI. ↑