Introduction[1]

Dialectical materialism is a philosophy, but not just for intellectual pleasure in ivory towers. Dialectical materialism has found its philosophers everywhere: among activists on the street, guerilla fighters, in workers’ and peasants’ movements, among politicians and academics. The use of dialectic materialism has spread globally, which makes it distinct from other philosophies. The purpose of dialectic is to analyze the world and to use the theory to guide the practice of revolution.

In times of crisis and turmoil, it can be wise to take a step back and consult dialectical materialism. Not as an escape from reality, but in order to get a basic grip on how to analyze a difficult situation. When Lenin, in his exile in Switzerland in 1914, experienced the split in the Second International between social democrats and communists concerning the attitude to take toward inter-imperialistic war, he turned to the study of dialectical philosophy to develop his method of analyzing and describing what was going on.[2] The result was a stream of groundbreaking analyses of imperialism, war, and their effects on the socialist movement.

When the Chinese communist movement was in a difficult and crucial situation after “The Long March” and the Japanese invasion in 1973, Mao – like Lenin – turned towards dialectic materialism. He studied and lectured the cadres in the camps in Yanan in dialectic philosophy. The purpose was to give them the capability to developed strategies for the decisive coming struggle.[3]

In the current situation, where the capitalist crises present a complex mixture of interrelated conflicts, I feel a need for sharpening the Marxist tools in order to analyze capitalism and develop strategies to overcome it. Dialectic materialism focus is on change. Actually, it can only be properly studied when you are committed to action. Dialectic’s core concept of contradictions builds a bridge between theory and practice. It is not just a valuable tool for the analysis of complex relationships; it also tells us how to intervene.

In this essay, I will shortly explain the concept of contradiction, and then give a summary of world history through the lens of the principal contradiction. Finally, I will try to map out the interactions of the main contradiction today.

The Principal contradiction

My basic position is that the capitalist system is a world-system in the sense of Immanuel Wallerstein.[4] Capitalism has one global division of labor. The transnational company’s chains of production globalize production and consumption. The law of value is thus globalized as stated by Samir Amin.[5] If the world system is one “thing” and thereby one process, then this system according to dialectic materialism has a principal contradiction, which drives the system forward.

Mao’s contribution to dialectics is his development of the concept of “principal contradiction”:[6]

“If in any process there are a number of contradictions, one of them must be the principal contradiction playing the leading and decisive role, while the rest occupy a secondary and subordinate position. Therefore in studying any complex process in which there are two or more contradictions, we must devote every effort to finding its principal contradiction. Once this principal contradiction is grasped, all problems can be readily solved.

The principal contradiction and the other contradictions interact in a continuer process, where the hierarchy of contradiction never are totally fixed. To locate the principal contradiction is to pinpoint a contradiction, which at a certain time and space contains energy or force of ideas, practical methods, technologies, and actions that influence the broad field of contradictions.

When we talk about the principal contradiction, in the Maoist sense, is not the general and abstract contradictions inherent in the capitalist system, like productive forces versus relation of production, it is the specific historical contradictions, driven by class struggle and interstate competition for hegemony. The globalized capitalist system has developed by successive and changing principal contradictions, which have decisively influenced regional, national and local contradictions. This exposure has created feet-backs, which interact and change the principal contradiction.

Why is it important to identify the principal contradiction?

When Mao states: “Once this principal contradiction is grasped, all problems can be readily solved.” The expression “readily solved” should be taken with a grain of salt, not least when we talk about social problems and revolution in a country the size of China. What Mao means when he says “readily,” is that you have a reliable guide for further analysis once you have identified the principal contradiction. In other words, the decisive problem in defining useful strategies, policies, means of propaganda, and military efforts are solved. The ultimate purpose of identifying the principal contradiction is to intervene in it. We cannot create principal contradictions, but we can influence the aspects of existing ones so that the contradictions move in a direction that serves our interests. Identifying the principal contradiction tells us where to start.

Discussions on general contradictions such as “productive forces versus relations of production,” “proletariat versus bourgeoisie,” and “imperialism versus anti-imperialism” usually don’t cause much controversy among Marxists. Disagreements begin when it comes to specific contradictions; for example when we must identify the most important contradictions at a given time and place, the contradiction with the highest revolutionary potential. Note that Mao speaks of “finding” the principal contradiction in the quote above. This cannot be based on speculation. Theoretical knowledge about dialectical materialism cannot replace concrete studies. “Contradiction” is an abstract concept, but real-life contradictions on the ground are very concrete. Moreover, we cannot simply copy the analysis of one country and apply its results to another; we convolute their respective particular contradictions.

The Two Aspects of the Contradiction: Unity and Struggle

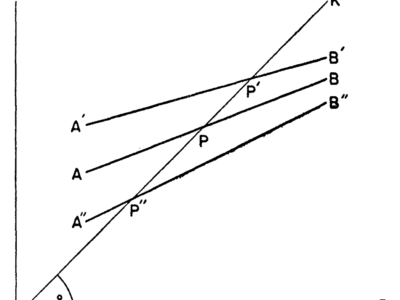

Once we have identified both the principal contradiction and the particular contradictions it interacts with, we have to take the next step and study both the struggle and the unity of the contradictions’ two aspects. In particular, we have, as Mao states to identify the principal aspect:[7]

Of the two contradictory aspects, one must be principal and the other secondary. The principal aspect is the one playing the leading role in the contradiction. The nature of a thing is determined mainly by the principal aspect of a contradiction, the aspect which has gained the dominant position.

On the one hand, the two aspects form a whole. They influence, complement, and are dependent on one another. Without the bourgeoisie, there is no proletariat. On the other hand, the aspects exclude one another. Power relations between the aspects change constantly. Sometimes, the aspects appear to be in balance. However, this is temporary and relative. The change, the imbalance, and the struggle are absolute.

It is the struggle between the aspects, which drives the development of capitalism forward. The struggle entails two forms of motion: one is smooth and unremarkable, and the other is characterized by sudden change. During the former, there are quantitative changes; during the latter, qualitative leaps. When a contradiction appears to be in balance, we go through a phase of quantitative change. When things change abruptly, we have entered a phase of qualitative change.

What is unique about dialectical materialism is that it is an analytic method, which can be used with the goal of changing the world. To do this contradictions need to be studied concretely, both in their historical and geographical context. We need to identify the central forces and actors in order to intervene in a way that makes the contradiction develop in the direction we want it to. It does not suffice to remain on the abstract level. Principal contradictions can be seen, felt, and traced very concretely. They are tangible in economic developments and political conditions. Actors can be identified in the form of governments, parties, corporations, and social movements.

The history of the principal contradiction

In the following pages, I will present a concentrated version of the history of capitalism through the lens of the changing principal contradictions. To analyze and develop strategies for a specific time and place, much more thorough studies of the complexity of how the world’s many contradictions interact are needed. However, the principal contradictions are necessary departure points allowing us to zoom in on the specific location.

The Establishment of the Capitalist World System

The perspective of the principal contradiction recognizes that global capitalism ties all developments in the world to one another. If we look at world history, this has not always been the case. Although traders and pilgrims were sailing across the Indian Ocean, to and from East Africa, Arabia, India, and China, the Vikings sailed to both Russia and Canada around the year 1000. These expansionist tendencies were the result of local contradiction. Up until 1500, there existed different societies across the world that had little interaction. The Maya of the Yucatán Peninsula were traveling as far north as the Mississippi River Valley and as far south as Colombia, however, the American continent had only had sporadic contact with the rest of the world. The territories today known as Australia and New Zealand had hardly any. The societies of China and India were the most developed. Cities in the Middle East served as important trading centers along the routes between Asia, Africa, and Europe. Besides the North Italian city-states, Europe’s importance was limited.

There were repeated attempts at various places to introduce a capitalist mode of production, reaching from China’s Song dynasty to the Arab-Persian Abbasid Caliphate. The increase in international trade during medieval times gradually shifted focus from use value to exchange value. The Italian city-states developed extensive trade in the Mediterranean in the fifteenth century and established advanced banking and finance systems. Venice sponsored expeditions to China. The world had previously known empires that covered vast geographical areas: that of the Egyptian pharaohs, the Roman Empire, The Chinese Empires the Ottoman Empire, and others. But no principal contradiction affected the entire world. If we need to name a year that stands for the beginning of such a process, 1492 is a good choice. That year Europe, personified by Christopher Columbus, began its military, economic, political, and cultural domination of the world. At the same time, the contradictions within feudalism, as well as the contradiction between feudalism and merchant capital, sharpened in Europe. Both the absolute monarchs and merchant capitalists had an interest in “discovering” the world in order to expand their powers and wealth.

Colonialism and the development of European capitalism are inseparable. As capitalism conquered the world, its contradictions became ever more central for societies everywhere. Capitalism had always had a global dimension; it is fitting that Immanuel Wallerstein described its development from the fifteenth century to the end of the nineteenth century under the title The Modern World-System.[8]

Capitalism originated in the triangle London-Paris-Amsterdam. From there, it spread to the entire world. Military might – not least naval military might – was crucial. Many wars had been fought in Europe during the feudal era and both the technology and the art of war were highly developed. European history knows of the “Hundred Years’ War” (1337-1453) and the “Thirty Years’ War” (1616-1648). No military power outside of Europe was a match for the professional European soldiers and their weapons. Unsurprisingly, the first colonies were established by Europe’s leading naval powers at the time: Portugal and Spain. What took them out into the oceans were their powerful fleets. Portuguese warships stood behind Portuguese dominance in the Indian Ocean, and Spanish swords and armor were behind the annihilation of the Inca and Maya in South America.

Conquering the “new world,” blending trade with plunder, gave a boost to capitalism in Europe. The Spanish colonies’ most important assets were silver and gold, which fueled manufacturing in Europe and were used as payment for goods from Asia. Europe had no goods in the 17th and 18th centuries that would have been of interest to the Asian powers. Spanish and Portuguese colonialism did not give rise to capitalism in Spain in Portugal. Their silver and gold were used to trade with the Netherlands, England, France, and Germany. Only there are they invested in capitalist development. Spain and Portugal sponsored the bourgeoisie in Western Europe, while their own aristocracies indulged in feudal overconsumption.

Colonialism did not just strengthen capitalism in Europe; it also broke down traditional relations of production in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. This created new contradictions: first, between the colonial powers and the colonized; later, between the colonial powers and settlers.

The emergence of the capitalist world-system was a polarizing process. It divided the world into a center and a periphery. Colonialism was a catastrophe for the colonized: the destruction of African societies and the near extinction of the indigenous societies of the Americas only took a few decades to complete.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the European merchant capital pulled formerly isolated cultures and economies into a world system. Through political quarrels and war, the Netherlands, Britain, and France began to divide the world outside of Europe between themselves. They established strategic trading posts along the world’s main shipping routes. With the help of naval military power and the forts they had established in the colonies, they kept competing nations’ traders from the territories they controlled. With the use of slaves and coerced labor, much of it from oppressed indigenous populations, plantation economies were established and raw materials extracted to support industrialization in Europe.

Capitalism’s Contradictions and Colonialism (1850–1900)

Marx and Engels describe the establishment of the capitalist world system in The Communist Manifesto:

“Modern industry has established the world market, for which the discovery of America paved the way. This market has given an immense development to commerce, navigation, to communication by land. This development has, in its turn, reacted to the extension of industry; and in proportion as industry, commerce, navigation, and railways extended, in the same proportion the bourgeoisie developed, increased its capital, and pushed into the background every class handed down from the Middle Ages. … The need for a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere. … The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilization. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, in pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.”[9]

As continent after continent, country after country was brought under the control of the European powers, capitalism’s contradictions gradually became central for economic and political development across the globe. The manufacturing of machines and textiles characterized capitalism between 1800 and 1870. England developed almost a world monopoly on industrial production. The productive forces developed rapidly and an enormous amount of goods entered the market. However, the exploitation of the working class put a limit on buying power. On the one hand, the capitalists wanted to keep wages low to ensure high profit rates; on the other hand, they relied on the working class to buy their products. By 1850, the dilemma became urgent. The capitalists rejected higher wages, overproduction came, capitalism entered its first crisis, and social contradictions increased. In 1848, The Communist Manifesto was written against this background: “A specter is haunting Europe – the specter of communism”. However, it remains a haunt. The capitalists’ solution was to search for new opportunities for investment, raw materials, and markets overseas. The “production versus consumption” contradiction shattered national economic frameworks and drove capital out into the world. The British Empire was the most significant manifestation of this.

Colonialism solved both the problem of falling profit rates and the lack of buying power. It brought profitable investment opportunities in the plantation economies and raw materials for industrial production in the home countries. It created the basis for growing shipyards and railway lines that could transport goods. Colonialism also strengthened buying power in England. Superprofits from colonial investments and cheap colonial goods allowed for a gradual rise in wages. These developments were replicated in France, Germany, Holland, and the Netherlands.

The contradictions in European capitalism were solved by colonialism, which in turn dissolved old contradictions and created new ones in the rest of the world. Marx described the consequences of British rule in India: [10]

“However changing the political aspect of India’s past must appear, its social condition has remained unaltered since its remotest antiquity until the first decennium of the 19th century. … England has broken down the entire framework of Indian society, without any symptoms of reconstitution yet appearing. This loss of his old world, with no gain of a new one, imparts a particular kind of melancholy to the present misery of the Hindoo, and separates Hindostan, ruled by Britain, from all its ancient traditions, and from the whole of its past history.”

Mao Tse-tung gave a similar description of China: [11]

“Chinese feudal society lasted for about 3,000 years. It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century, with the penetration of foreign capitalism, that great changes took place in Chinese society. … The history of China’s transformation into a semi-colony and colony by imperialism in collusion with Chinese feudalism is at the same time a history of struggle by the Chinese people against imperialism and its lackeys.”

But it wasn’t only in the world’s two most populous nations, India and China, where contradictions that originated in the capitalist West increasingly affected national ones. By 1900, the whole world had been divided between imperialist powers.

At first European colonization meant that the contradiction between the colonial powers and the colonized people became dominant in the periphery of the capitalist world system. However, a new important contradiction soon emerged between European settlers and the governments of their home countries. In North America, this contradiction soon led to serious strife. In 1776, the USA declared itself independent from Britain. Several South American colonies followed suit soon thereafter, cutting themselves loose from the declining Portuguese and Spanish empires.

Colonialism also mitigated the contradiction between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat at home in the center. The “specter of communism” was tamed by reformism and the institutionalization of the working-class movement. Political power was divided between the bourgeoisie and the working class through common suffrage and parliamentarism. The trade union movement accepted the capital’s right to control and administer labor. In exchange, capital accepted the trade union movement as a legitimate political counterpart. An increasingly “social” state reflected this compromise.

But the way, in which the contradiction between production and consumption was solved in the center, created new contradictions. Partly between the European powers and the colonized people in the periphery of the world system, but especially between the European powers. The necessity to act as an imperialist power to secure both the accumulation of capital and social peace at home increased inter-imperialist rivalries.

Inter-imperialist Rivalry I (1880 – 1917)

Based on the superiority of its industrial production, Britain built an empire “on which the sun never set.” The British Empire contributed to increased global integration in economy, transport, communication, culture, and administration. However, already in the late nineteenth century, Britain was challenged economically and politically by continental powers such as Germany and France and by the USA. In the 1890s, the USA overtook England as the world leader in industrial production. The twentieth century brought intense national rivalry and capitalism became more fragmented.

No one can doubt that the principal contradiction during World War I was the inter-imperialist contradiction between Britain, France, and the USA on one side, and Germany on the other. Lenin observed that there was no escape from the ramifications of this contradiction anywhere:

“… it is seen how most of the nations [in Europe] which fought at the head of others for freedom in 1798-1871, have now, after 1876, on the basis of highly developed and ‘overripe’ capitalism, become the oppressors and enslavers of the majority of the populations and nations of the globe. … The peculiarity of the situation lies in that in this war the fate of the colonies is being decided by the war on the Continent.” [12]

Lenin also stated that World War I created the external conditions for the Russian Revolution. The inter-imperialist contradictions amplified Russia’s national contradictions and opened up a “window of opportunity” for revolutionary change in the semi-periphery of the capitalist world system.

The Russian Revolution, in turn, affected the contradictions in Europe. It inspired revolutionary uprisings in Germany, Hungary, and Finland, and it created a new crucial contradiction between “actually existing socialism” and the imperialist countries. The first consequence was foreign intervention in the Russian civil war. Mainly France and England, but also the USA, Canada, and Japan supported the counterrevolutionaries. In 1920, there were about 250,000 foreign troops on Russian soil. Winston Churchill stressed the importance of “strangling Bolshevism in its cradle.”[13] The fear of a Bolshevik revolution also influenced the relationship between capital and labor in Europe. It brought further reforms and capital’s acceptance of Social Democrats’ participation in government and therefore in capitalism’s administration.

Capitalist Crisis and the State (1918 – 1930)

While it is easy to identify the principal contradiction during the inter-imperialist war, it becomes more difficult when contradictions are less pronounced in times of peace. One thing that was evident was that the USA had become the leading power, illustrated by President Woodrow Wilson’s central role at the Versailles Peace Conference of 1919-1920; a conference that sought to establish a new world order.

The USA economy was as big as that of Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Russia, and Japan combined. The dominant position created contradictions for both allies and enemies. European colonialism still stood in the way of the USA’s global ambitions. Japan was a serious contender for the control of Southeast Asia and the Pacific region. In 1923, Lenin expressed the hope that the contradiction between Western and Eastern imperialism (the USA vs. Japan) would provide a bit of breathing room for the Soviet Union. In 1928, Mao described how the contradictions among the landlords in China reflected the contradictions among the imperialist powers, and how this created the conditions for “Red power” to emerge in the country:

“The long-term survival inside a country of one or more small areas under Red political power completely encircled by a White regime is a phenomenon that has never occurred anywhere else in the world. There are special reasons for this unusual phenomenon. It can exist and develop only under certain conditions. First, it cannot occur in any imperialist country or in any colony under direct imperialist rule, but can only occur in China which is economically backward, and which is semi-colonial, and under indirect imperialist rule. For this unusual phenomenon can occur only in conjunction with another unusual phenomenon, namely, the war within the White regime.” [14]

In 1929, the Great Depression came with the Wall Street stock market crash. The USA now experienced what England had experienced the century before: a crisis of overproduction. The USA had come out of World War I as the big winner. All fighting had happened on European soil and damaged their industry, while the demand for war material had boosted US industrial development. US capitalism experienced a boom that created a consumer society in the 1920s, thirty years before it was established in Europe. New industries were thriving, producing cars, airplanes, and appliances. Automobilization in the USA in the 1920s was at a level it reached in Europe only in the 1960s. The term “Fordism” was used to describe the parallel development of mass production and a consumer market. US capitalism enjoyed the “Golden Twenties,” but the market could not keep up with the acceleration of production. This ended in a financial crisis that spread like wildfire to the rest of the world. But a solution to the imbalance between production and consumption was on its way. Paradoxically, it was the labor movement and its rising political influence on the working class that saved capitalism.

The governments of the industrialized capitalist nations initiated state-sponsored infrastructure programs that increased employment and thereby buying power. They also regulated the capitalist market through specific economic policies, following the propositions of British economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynes saw the reason for capitalism’s crisis in demand being too low to secure full capacity utilization and employment. According to Keynes, production did not create an adequate market by itself, contrary to what the old economists had claimed. It was the opposite: demand determined adequate production.[15] In the USA, these reforms were exemplified by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” of the 1930s. The Social Security Act of 1935 introduced better pensions, an unemployment insurance system, and various welfare programs. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 introduced a minimum wage and regulations for overtime pay. Similar programs were introduced in Western Europe, where social-democratic parties had risen to power. They invested in transport, housing, and social welfare, which created jobs and strengthened the domestic markets. The markets were regulated by monetary policies. These were the first steps toward the capitalist welfare state.

However, the solution that was found to contain the contradiction between production and consumption lay the basis for the future contradiction between the national welfare state’s need to regulate and control transnational capital. A condition for the establishment of the welfare state and increased buying power of the working class in the capitalist center was the continuation of imperialism to secure the profit rates and thereby the accumulation of capital.

Inter-imperialist Rivalry II (1939 – 1945)

In the mid-1930s, the inter-imperialist rivalry became yet again the principal contradiction in the world system. Germany sought, once more, to become a major global power based on the strength of its industrial production. The rivalry escalated when Germany invaded Poland, and Britain declared war on Germany. It became a world war when Germany attacked the Soviet Union, and Japan the USA, in 1941. The principal contradiction during World War II was expressed in the “Axis Powers” (led by Germany, Japan, and Italy) fighting the “Allies” (led by the USA, Britain, and the Soviet Union). This conflict affected all other contradictions worldwide.

Germany intended to become Europe’s strongest power and break the old colonial powers’ grip on Africa and Asia. Japan intended to turn all of China into a Japanese colony. Had the Axis Powers won the war, Germany, and Japan would have probably divided the Soviet Union between them. Like World War I, World War II was a fight over control of the world’s territories. As in World War I, the fate of the colonized peoples in World War II was entirely in the hands of the imperialist powers. But compared to World War I, there was much more fighting in the colonies. This played a role in the era of decolonization that followed.

As we know, Germany, Italy, and Japan lost the war. The empires of Britain, France, and Nederland were weakened. The USA consolidated its position as the leading imperialist power. The Soviet Union, however, was also a winner. The military strength it had built since the Russian Revolution proved powerful enough to overcome the German war machine. Despite the war’s immense human and material costs, the Soviet Union had established itself as an important political player in the world system.

The principal contradictions that determined the world’s development under capitalism up to World War II could all be located in and among the imperialist powers. They affected all others, reshaped old ones, and created new ones.

The American World Order

In the fifty years that followed World War II, the USA was the dominant aspect in three important contradictions:

- The USA vs. the old colonial powers (England, France, Germany, Japan)

- The USA vs. the socialist bloc (Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China)

- The USA vs. the Third World

In order to determine which one of the three was the principal contradiction at a given time, we first need to look closer at each of them and at how they interacted with one another.

1. The USA vs. the old colonial powers

In this contradiction, the dominance of the USA was clear. Industrial production had grown and been modernized during World War II (not least because of economic planning), while western Europe’s and Japan’s industrial infrastructure lay in ruins. Europe’s recovery was dependent on US aid in the form of the Marshall Plan, which came with American conditions. Europe was to become a coherent lucrative market for US capital.

With the USA’s hegemonic role in the world economy, the tendency to globalize (evident during the formation of the British Empire) returned with a vengeance. Capital became significantly more transnational. Following the end of World War II, many international treaties were signed and related economic, political, and military institutions were founded to administer this increasingly global capitalism. The “United Nations,” with the Security Council and numerous subsidiaries for everything from development and culture to labor and health, was the most important. The international finance and banking system was reorganized under the Bretton Woods Agreement, which made the US dollar the “world currency” and solidified the USA’s leading global position. The USA also established a global network of about 800 navy and air force bases in 177 countries. These allow the US government to intervene militarily almost anywhere in the world at the drop of a hat. “No beach out of reach”.[16] At the end of World War II, the USA demonstrated the power of its nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After the war, the USA led the world’s most powerful military alliance, NATO, founded in Washington, DC, in 1949. US capital demanded “free enterprise” and put pressure on the European colonial powers to give up their colonies in Asia and Africa and open them up for US capital. (Latin America had already been treated as the USA’s exclusive backyard since the Monroe Doctrine in 1823.) In short, from the 1950s to the 1970s, the USA was the unquestioned leader of increasingly globalized capitalism, while Canada, Western Europe, Australia/New Zealand, and Japan acted as junior partners, subject to US interests.

2. the USA vs. the socialist bloc

The contradiction between the USA and the socialist bloc led by the Soviet Union increased after World War II. As expressed in the Winston Churchill quote above, the Soviet Union was considered an opponent of the West since its inception. But the victory over Nazi Germany had strengthened the Soviet Union’s position. Communist resistance movements – both in Europe and in the colonies – had played an important part in fighting the Axis Powers. The countries of Eastern Europe had been wrestled from German control, and East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania have declared people’s republics under communist-party leadership in the late 1940s. Yugoslavia and Albania were also countries that were, at least originally, friendly with the Soviet Union. The Chinese Revolution came in 1949 and the country became another people’s republic under communist-party leadership. That same year, the Soviet Union conducted the country’s first nuclear tests, which strengthened the socialist bloc’s geopolitical position. Essentially, the socialist bloc barred Western capitalism from roughly a third of the globe.

The contradiction between the imperialist countries and the socialist bloc was expressed in the division of Europe, the Berlin Crises leading to the Wall, the establishment of the military alliances NATO and Warsaw Pact, the Korean War, and the so-called Cold War with its nuclear arms race. Despite the socialist bloc’s strengthened position in the aftermath of World War II, the USA remained the dominant aspect in this contradiction. Any closer study of the Cold War reveals that the Soviet Union was the reactive (defensive) part (aspect).

3. the USA vs. the Third World

Finally, there was the contradiction “USA vs the Third World.” This contradiction was not new. The USA had since its foundation played an imperialist role in Central and South America, the Caribbean, the Philippines, and islands in the Pacific Ocean. However, with decolonization and neocolonialism, this contradiction became more pronounced. The global network of US navy and air force bases was not only established to combat communism but also to increase the USA’s influence in the Third World. At the same time, the situation in the Third World was changing. This was the beginning of the era of decolonization, with national liberation movements. At the Bandung Conference of 1955, many Asian and African countries stressed the importance of independence from both East and West and the development of national economies. Iran nationalized its oil industry in 1951; Egypt took control of the Suez Canal in 1956; Iraq experienced a nationalist revolution and the nationalization of its oil industry in 1958. In countries ranging from Vietnam, Indonesia, Burma, and Malay, to Cuba, and Guatemala, anti-imperialist liberation movements were on the offensive. Had they been victorious, imperialism’s reach would have shrunk even further, then a third of the globe already lost to the socialist block In other words, they had to be fought.

Let us look at the interaction of the three contradictions sketched above to identify the principal contradictions during different phases between 1945 and 1975.

Europe (1945–1949)

The USA and the Soviet Union were the victors of World War II, militarily and politically. The American president Roosevelt and Stalin wanted the colonial era to end and that the colonies should be granted independence. This position was first and foremost directed against Britain and France, but also against other colonial powers such as the Netherlands and Belgium. But Roosevelt and Stalin strongly disagreed about the political order of Europe. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the importance of these contradictions shifted several times, but what remained constant was that the USA was the dominant aspect of both contradictions.

The Red Army ensured that Eastern Europe remained under Soviet influence. In Western Europe, the economic challenges of the postwar period and the prestige gained by pro-Soviet communist parties in fighting the Nazis raised the specter of a turn toward socialism. That’s why Winston Churchill announced an “Iron Curtain” in Europe during his visit to the USA in 1946. One year later, the US Marshall Plan was passed to help rebuild Western Europe, undermine the wish for socialism, and create new markets for US goods, all at the same time. In the first years after the war, Europe was the USA’s priority. This allowed the communists in China to defeat Chiang Kai-shek and imperialism and establish the People’s Republic. Mao Tse-tung described the situation as follows:

“The U.S. policy of aggression has several targets. The three main targets are Europe, Asia, and the Americas. China, the center of gravity in Asia, is a large country with a population of 475 million; by seizing China, the United States would possess all of Asia. … But in the first place, the American people and the peoples of the world do not want war. Secondly, the attention of the United States has largely been absorbed by the awakening of the peoples of Europe, by the rise of the People’s Democracies in Eastern Europe, and particularly by the towering presence of the Soviet Union, this unprecedentedly powerful bulwark of peace bestriding Europe and Asia, and by its strong resistance to the U.S. policy of aggression. Thirdly, and this is most important, the Chinese people have awakened, and the armed forces and the organized strength of the people under the leadership of the Communist Party of China have become more powerful than ever before.”[17]

As early as 1945, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander in the Southwest Pacific Area, argued for US military intervention in China on the side of Chiang Kai-shek, but the US government limited itself to sending money and weapons to the Kuomintang. This, as we know, was insufficient. The People’s Liberation Army won the civil war and proclaimed the People’s Republic of China. The contradiction between the communists and the Kuomintang in China was solved nationally, without direct foreign intervention, because, globally, other contradictions were dominant: the USA vs. the Soviet Union, and the USA vs. Europe.

The USA vs. the Soviet Union and Decolonization (1945–1956)

India did not attain independence in 1947 because of a successful liberation movement or Mahatma Gandhi. India became independent because the USA wanted to dissolve the colonial empires of the European powers. This was not out of sympathy for the colonized, but because the USA themselves wanted to reap the benefits of exploiting them.

However, communists across East Asia inspired by the Chinese success tried to use the vacuum created by the Japanese defeat to gain independence. Sukarno, leader of the nationalist movement in Indonesia, declared the country independent in 1945. Also in 1945, Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam independent, liberating vast areas of the country. There were also guerrilla wars against Britain in Burma and Malaya, and against the US in the Philippines.

The USA’s position on decolonization was characterized by two things: (1) the demand for decolonization in the context of the “USA vs. the old colonial powers” contradiction; (2) the governments of the newly independent countries had to fit in with the USA’s economic, strategic, and political plans in the context of the “USA vs. the socialist bloc” contradiction. The British led a barbaric colonial war against Malaya and got full US support because the Malayan liberation movement was led by communists. The same applied to the French fighting anti-colonial movements in Indochina. On the other hand, the Netherlands was forced by the USA to grant Indonesia independence because Sukarno’s vision for the country had become acceptable to US interests. The USA got militarily involved in the Indochina conflict when the French seemed incapable of defeating the communists after the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

The USA also fought a bloody war in Korea from 1950 to 1953. Korean communists were an important force in the resistance against the Japanese. In order to prevent them from seizing power after independence, the US army pushed them to the north. China entered the war and drove the US forces back to the thirty-eight parallel.

The contradiction between the West and the socialist bloc also impacted power relations between capital and labor in the West. Capital’s fear of communism led to cooperation with social democracy. Social-democratic parties formed governments in several European countries, expanding the capitalist welfare state. Wealth was redistributed via taxes and the public sector was strengthened, while the class struggle was mitigated and institutionalized. Transnational corporations and finance capital, growing forces in global capitalism, were, however, staunchly opposed to “paternalistic” state control and regulation. A contradiction, which became dominant a few decades later.

The “USA vs. the socialist bloc” contradiction took on a new form after the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956. Slogans such as “peaceful coexistence” and “peaceful transition to socialism” transformed the contradiction between the USA and the socialist bloc from one between two conflicting economic and political systems to a more traditional national contradiction between two superpowers and their spheres of interest.

Decolonization (1956–1965)

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, decolonization took big steps, but not primarily because of the success of liberation struggles. In various colonies, Madagascar and Malaya among them, communist liberation movements were brutally repressed before they could get to that point. Instead, US-friendly regimes were installed. In Africa, decolonization happened either without any liberation movements or with liberation movements whose influence on independence was very limited. Africa’s destiny was, once again, decided without Africans. The decisive factors were economic developments in capitalism’s center and the contradictions between imperialist powers, first and foremost between the USA and the old colonial powers of Europe.

Most of the newly independent countries in Asia and Africa were under petty-bourgeois leadership and tried to position themselves as the “Third World” between the West and the East. This was the message of the 1955 Bandung Conference. But there were exceptions: in Algeria, the National Liberation Front seized power in 1962 after many years of fighting against France and European settlers, at the cost of one million lives; in the Congo (Zaire), independence only came after a violent conflict between factions representing the economic interests of different foreign powers. In both cases, significant settler populations wanted to defend their privileges. The Cuban Revolution of 1959 took the US entirely by surprise; the attempt to correct this misjudgment through the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1959 failed.

The Third World on the Offensive (1965–1975)

As the Soviet Union downplayed the “revolutionary socialist” element at the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party in 1956, China upped its revolutionary rhetoric, especially with the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1972. The conflict between the world’s two biggest communist powers affected the communist movement worldwide and weakened the socialist bloc vis-à-vis the USA.

The Sino-Soviet split paradoxically coincided with a radicalization of anti-imperialist movements in the Third World. Inspired by the anti-imperialist victories in Cuba and Algeria and the successful resistance in Vietnam, strong revolutionary movements appeared in numerous countries, among them Cambodia, Laos, India, Nepal, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Palestine, Lebanon, South Yemen, Oman, Bissau Guinea, Angola, Mozambique, Rhodesia South Africa, South West Africa, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Mexico, Brazil, Uruguay, and Chile. In some of these countries, socialist movements came to power.

However, the economic liberation from imperialism and the transition to an economy serving the people’s interests proved much more difficult than attaining political independence. Most of the newly independent countries in the Third World had economies that had been exclusively adapted to imperialist needs during colonization. They remained dependent on exports to the global market in order to survive. Political independence led, in most cases, to capitalist applications of “development economics.” But, there were also attempts to unite Third World countries with shared export industries, based on oil, bauxite (aluminum), copper, or sugar, in order to strengthen their position on the world market. The most were the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). OPEC demanded a bigger share of the profits made by the “Seven Sisters” Exxon, Shell, Gulf, Mobil, BP, Texaco, and Chevron. With the Israeli-Arab Six-Day War of 1967, OPEC also became a political player. In order to put pressure on the West which supported Israel, OPEC raised the price of oil. During the Israeli-Arab Yom Kippur War of 1973, OPEC introduced an oil embargo against the USA and Western Europe and then doubled oil prices, which resulted in an economic recession. Politically, Third World countries united in the Non-Aligned Movement, which raised the demand for a “New International Economic Order.”

The USA vs. Europe (1965–1975)

During the Vietnam War, the “USA vs. Europe” contradiction flared up again. France used the USA’s problems to launch a campaign against the USA’s gold reserves and the US dollar’s status as the “world currency.” In order to finance the war in Vietnam, the Federal Reserve System lets the money printing machines run wild, and there was no correlation between the amount of US dollars in circulation and the USA’s gold reserves. With the dollar rate falling, the banks began to exchange their dollars for gold, which led to the end of the so-called gold standard. This had far-reaching consequences for international finance. Ironically, it was the 1968 youth uprising in France, with its strikes and factory occupations that put a halt to the French crusade against the dollar.

The Principal Contradiction in the World (1945-75)

Let us now try to identify the principal contradictions from the end of World War II to 1975.

In the years following World War II, the “USA vs. the socialist bloc” contradiction was the world’s principal contradiction. With American consumer society firmly established, it was now time to conquer the European market and the rest of the world. As a result of the war, Western Europe was forced to open its markets and accept the process of decolonization that the USA demanded.

The biggest barrier to world domination for the USA was the socialist bloc. The Soviet Red Army had liberated Eastern Europe and significant parts of the Balkans from Nazi Germany, putting these regions beyond the reach of the US. The Chinese Red Army had defeated US ally Chiang Kai-shek and proclaimed the People’s Republic of China, blocking US access to the world’s most populous nation. The contradiction between the USA and the socialist bloc was expressed in the military alliances of NATO and the Warsaw Pact and in the nuclear arms race, which extended all the way into space. It also found expression in the Korean War, in which China acted as the USA’s counterweight, and in the Cold War which included the Berlin Crisis of 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Another consequence of this contradiction was the capital’s acceptance of social-democratic governments in the West as a lesser evil than would, hopefully, contain communism. Anti-communist sentiments were rampant. The USA established and sponsored a secret anti-communist network in Europe for “stay-behind” operations under the codename “Operation Gladio.” In the USA, McCarthyism stood for an anti-communist crusade aiming to remove everyone with communist sympathies from public office, institutions of learning, and the cultural world. The “USA vs. the socialist bloc” contradiction also affected the entire decolonization process.

This contradiction remained the world’s principal contradiction until the mid-1960s. By then, the socialist bloc had been weakened by the hostilities between the Soviet Union and China and by economic problems in both countries. The “USA vs. Europe” contradiction was relevant but remained secondary because of the USA’s clear dominance. The “USA vs. the Third World” contradiction became increasingly important, with the USA being confronted with ever more radical and socialist-leaning anti-imperialist movements. At the same time, there was a new important contradiction taking shape, namely, the one between increasingly powerful transnational corporations and the welfare state.

The imperialism vs. anti-imperialism” contradiction was nothing new. It had existed since the late nineteenth century, but its importance grew with neocolonialism and US hegemony. US President Dwight D. Eisenhower presented the world with his “domino theory,” according to which a communist victory in Vietnam would lead to all Southeast Asian countries becoming communist, one by one. The domino theory was also applied in the Middle East, where there were strong anti-imperialist movements in Iraq, Iran, Palestine, and Yemen. In Africa, it was cited with regard to South Africa and the Portuguese colonies and in South America with regard to the socialist government of Salvador Allende in Chile. Che Guevara presented an anti-imperialist version of the domino theory when he called for “one, two, many Vietnams.”[18]

The alliance between anti-imperialist movements in the Third World and the socialist bloc threatened to cut off even more territories from the capitalist world market, along with their raw materials and cheap labor. This was a major reason for the USA escalating the war in Vietnam. In 1969, there were 545,000 US troops stationed in the country; during the war in Indochina, more bombs, including chemical and biological weapons, were dropped than during World War II. The fact that both the Soviet Union and China had nuclear weapons deterred the USA from using theirs. The resistance of the Vietnamese people inspired the entire Third World, while anti-war sentiment grew in the USA as more and more soldiers returned home in coffins.

From around 1965 to 1975, the contradiction between imperialism headed by the US and the anti-imperialist movements was the principal contradiction in the world. The demands for a New International Economic Order and the establishment of OPEC and similar organizations were institutional results of this contradiction. The contradiction was also crucial for the worldwide uprisings of 1968. Even in the USA, politics were dominated by the war in Vietnam and the resistance against it. The struggles of African Americans were explicitly tied to the fight against US imperialism, not least in the Black Panther Party. Economically, the contradiction was expressed in the dollar crises of 1967-1968 and 1971. In Europe, the oil crisis of 1973 was a result of OPEC raising the price of oil by 400 percent.

But history would show that economic liberation from imperialism did not follow political independence in the Third World. The capitalist world market was too strong and the anti-imperialist movements too fragmented, unable to become the dominant aspect in the “imperialism vs. anti-imperialism” contradiction.

Despite the contradiction imperialism vs anti-imperialism was only the principal contradiction in the rather short period between 1965 to 1975, has imperialism been a necessary aspect of capitalism throughout its history. Access to raw materials cheap labor and markets were necessary to solve the problem of overproductions, which first became evident in Britain in the nineteenth century.[19] Lenin described how the necessity of imperialism leads to inter-imperialist rivalry and war. The US hegemony after World War II was based on colonialism replacement by neocolonialism. The need for imperialism has been a constant driver in capitalism.

By the mid-1970s, anti-imperialism began to wane despite the victories in Vietnam and in the Portuguese colonies in Africa. Anti-imperialism had reached its peak and a new imperialist offensive was on the way. First, however, the right conditions had to be established “at home” in the West.

Capital vs. the State

The following decades saw a new principal contradiction emerge: one between capital, now in the form of ever more powerful transnational monopoly capital, and the nation-state. This contradiction had been growing steadily since the “social state” saved capitalism in the 1930s; it was amplified by the development of the welfare state in the 1950s and 60ties.

The “capital vs. the state” contradiction is inherent in capitalism. Capital hates the state but it cannot live without it. The state is the necessary “super-capitalist” that administers the system to prevent it from crashing.

The state is also the central political entity in capitalism’s transnational institutions. Transnational capital is therefore not detached from the nation-state. The US government will always look after the interests of US corporations first, the German government after the interests of German ones, and so forth. Nation-states provide the political and military means for the national bourgeoisie to compete with one another in the struggle over global market shares and investment opportunities. The state also maintains “social peace” – if necessary, with violence and coercion. In its liberal parliamentary form, the state administers the relationship between the classes.

The social state had pulled capitalism out of the world crises in the 30ties and capital and state was successful tandem in the preparation and execution of the Second World War. In the postwar period, the social state and the development of the “consumer society” in parts of the Global North, providing capital with an expanding market. Yet both state and capital were build-ups for conflicts to come.

Monopoly capitalism developed with the revenue of some corporations exceeding that of smaller nation-states. These corporations operated more and more transnationally. However, the state’s role was strengthened, too: rebuilding Europe demanded central planning by the state, which lay the foundation – in terms of both infrastructure and administration – for the welfare state. The public sector grew, in health, education, and childcare as much as in transport, communications, housing, and elsewhere. To regulate capitalism, the welfare state relied on Keynesian financial and trade policies. The “social state” also promoted a redistribution of wealth via income and profit taxes, and it functioned as a mediator between capital and labor. This was most pronounced in Sweden, where the trade union movement, emboldened by the 1968 uprisings, proposed an “economic democracy” in which workers would gradually take over the means of production through employee funds.[20]

The pressure on capital culminated in the early 1970s. Besides the USA vs. the Soviet Union contradiction, the contradiction between imperialism and the socialist forces in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Southern Africa, and Latin America came to a head. Meanwhile, social democracy and the trade union movement became more and more demanding in Western Europe as a result of the “New Left” of 1968. There were even anti-capitalist currents in the USA as part of the anti-racist struggle and the resistance against the Vietnam War. In terms of the economy, “the oil crisis” erupted in 1973. There was high inflation in the West and stagnation in both production and consumption, a phenomenon referred to as “stagflation.” The West experienced its first serious recession since World War II. It also became clear that Keynesian methods were no longer effective in keeping global economic forces in check and protecting the nation-state from economic crises.

Capitalism was vulnerable and radical change seemed possible. But the revolutionary movement was too fragmented: the Soviet Union and China were divided by political and ideological quarrels, the national liberation struggles were not able to unite, and the newly independent countries of the Third World could not break the monopolies and escape the world market, and the New Left never mobilized broad popular forces against imperialism, only sections of youth and minorities. A common front against the system, which would have been necessary to topple it, was never built. Most importantly, however, capitalism was not out of options yet. If millions of people in the Third World and the socialist bloc could be integrated into the global labor and consumer markets, imperialism could be revived and the “window of opportunity” closed. This, however, required a weakening of the nation-state in the center.

Neoliberalism (1975–2007)

The “social state” was no longer part of capitalism’s solution but part of the problem. Not only that: it had now become its main opponent. Partly because welfare programs demanded a share of the capitalists’ profits via taxes, but mainly because the nation-state was a barrier to transnational capital’s global ambitions, which was key to a revived imperialism. The “social state” regulated financial flows and trade and, in collaboration with the trade union movement, determining wages, and labor conditions.

If transnational monopoly capital wanted not only to invest and trade globally but also to relocate production to countries where low wages and labor standards promised high accumulation rates, it had to free itself from state restrictions. This was the reason behind neoliberalism’s attack on the nation-state and trade unions. It was also the precondition for a new form of imperialism, the breakdown of the socialist block, and thereby a renewed global accumulation of capital.

Neoliberal political leaders such as Ronald Reagan in the USA and Margaret Thatcher in Britain launched an all-out attack on government regulations, public welfare programs, and the redistribution of wealth via taxes. They ensured capital’s free mobility, privatized the public sector, and limited trade union power. They demanded a shift from the “social state” to the “competition state”. This meant that the state’s main task was to compete with other states to create the best conditions for capital. From regulating and controlling transnational capital, the state now moved on to serve it.

The transfer of millions of industrial jobs from the Global North to the low-wage countries of the Global South increased the profit rate and the accumulation of capital. The Third World’s prior demand for a New International Economic Order was ignored. Instead, there were demands for “structural adjustments”: no restrictions on capital’s mobility, no protection of national industries, and no trade barriers. Any resistance against these new imperialist policies was crushed by modern military strategies, developed after the USA’s defeat in Vietnam. Neoliberalism also dealt a final blow to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, while China opened its borders for industrial production and trade. The European Union (EU), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the G-meetings are some of the transnational organizations, treaties, and events responsible for the political administration of global, neoliberal capitalism.

The principal contradiction in neoliberalism is that between transnational monopoly capital and the nation-state. Transnational monopoly capital became the contradiction’s dominant aspect. Even social democrats turned into neoliberals, as exemplified by Tony Blair’s “New Labour.”

Neoliberalism and Imperialism

Neoliberalism brought global economic integration. Investments, currency trading, and securities trading multiplied. The production itself was globalized in chains of production stretching from North to South and back again for consumption. Neoliberalism renewed and intensified imperialism to sustain the rate of profit. Imperialism became a fully integrated and necessary part of the globalized capitalist system. The intensified globalization of capitalism means that the principal contradiction no longer has to be geographically located in the center as it has been in the 19th and 20th centuries. The principal contradiction itself has become global. The outsourcing of industrial production to China was a result of the contradictions between transnational capital and the national welfare state in the center. Thirty years later, we witness a contradiction between the USA and China that is of great significance for the entire world. The ongoing economic crises are tied to contradictions in global capitalism. This applies not only to economic and political contradictions but also to the contradiction between capitalism and the ecosystem.

The State Makes a Comeback

Neoliberalism gave capitalism thirty golden years. However, contradictions develop and change and their aspects are in constant struggle. In short, it was unavoidable that neoliberalism would encounter resistance. The outsourcing of industrial production to the Global South brought cheap goods to the Global North but also meant the loss of many jobs and stagnation in wages. Privatization eroded the capitalist welfare state. Global inequality and imperialist wars led to millions of refugees, who, in the Global North, were seen as competitors for both wages and social services, not least by the social groups that had been most affected by the erosion of the welfare system.

As social democrats were compromised by their attraction toward neoliberalism, right-wing populism became the political trend to win, by the opposition to the consequences of neoliberal globalization. It became particularly strong with the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Tax deductions for the rich and the greed of finance capital and the big banks fueled the fire. The social contract that had long been seen as guaranteeing capitalist stability seemed torn apart.

Even if neoliberalism had weakened the trade unions and the workers’ movement in general, and even if the state no longer acted as a mediator between capital and labor, the working classes of the Global North were not powerless yet. They still had the weapon of parliamentary democracy, which they had been granted in the early twentieth century after a long struggle. The market might have been globalized and many transnational institutions established, but nation-state parliaments were still operating and making political decisions. Government power was not dead yet – and it was electable.

For a large section of the population in the Global North, neoliberalism’s pressure on wages, the erosion of the welfare state, and the “migration problem” provoked nostalgia for the strong nation-state as a bulwark against globalization’s damaging forces.

We are in a period of growing tensions and changes in the contradiction between neoliberalism and the nation-state. Neoliberalism’s political crisis has divided both capitalists and ordinary people between those who want a return to nation-based capitalism and those who want to see continued globalization. Some of the world’s biggest companies such as Google, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft are advocates of neoliberalism. They have established global chains of production and distribution that not easily can be rolled back. But the nationalist forces rallying against neoliberal globalization grow stronger. They have gained momentum in the working and middle classes of the Global North, entering governments in alliance with the national-conservative factions of capital. Nationalists in power use the nation-state mechanisms to undermine neoliberalism’s transnational institutions. We have entered a situation where economic power lies firmly with global capital, while political power is increasingly slipping into the hands of nation-based capital.

The contradiction between neoliberalism and –nationalist governments has been the world’s principal contradiction since the financial crisis of 2007-2008. The position of the nation-state has grown steadily stronger. It expresses itself in the USA with Donald Trump, in Britain with Boris Johnson, in Italy with Matteo Salvini, in Hungary with Viktor Orbán, and in Australia with Scott Morrison.

Trump’s promise to “Make America Great Again” rests on economic protectionism and military might. But Trump cannot just roll back thirty years of neoliberalism. Apple electronics, Nike shoes, and Levi’s jeans will not be produced in the USA as long as US wages are ten times those of Chinese or Mexican wages. Tariffs can slow down the neoliberal machine, but they cannot stop it. Trade wars just fuel the economic crisis.

In the European countries, the traditional political parties desperately try to define a middle ground between the demands of neoliberal capital and the growing popular demand for a stronger and nationalistic state. An impossible task. There are also left-populist parties in Europe trying to reinvent old social-democratic positions. However, in a world in which neoliberalism has removed many of the state’s economic tools, it is difficult to reintroduce Keynesian policies.

The nationalists seek to strike a new compromise between capital and labor, not based on a social-democratic mediation between the classes, but on national unity between the conservative factions of capital and the right-leaning sectors of the working classes. Politically, this unity finds expression in the authoritarian state that is also able to respond to an increasing level of conflicts in the world. The power that is geographically located (power over “territories”) regains importance vis-à-vis the power of the free, borderless market.

The contradiction between neoliberalism and nationalism is not confined to the Global North. There are several expressions of it in the Global South: Narendra Modi in India, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey. How the contradiction between neoliberalism and nationalism is going to play out in China is crucial for the future of the world system. China’s opening to the world market has created a class of capitalists strongly tied to neoliberalism; at the same time, China still has an important state-capitalist sector, and Chinese agriculture mainly satisfies national interests. Continued neoliberal globalization might fully integrate the Chinese bourgeoisie into capitalism, and therefore China as a whole. But neoliberalism’s crisis also means that Chinese export rates are falling, which creates economic problems and sharpens the class struggle between the neoliberal bourgeoisie and the country’s “new proletariat.” Increasingly, Chinese workers themselves are demanding the goods they produce for consumers in the Global North. An intensification of the class struggle in China will have significant global consequences, not least because strong left-wing working-class movements in China would inspire similar movements across the Global South. It would also amplify the contradiction between China and the USA. A new “Cold War” might be in the cards – and someone might very well turn up the heat.

The “neoliberalism vs. nationalism” contradiction creates many additional problems for capitalism. The institutions that were established to regulate global capitalism have been weakened. Donald Trump has criticized the WTO, NAFTA, and many other free trade agreements. The most recent G-meetings were fiascos, mainly because of Trump’s lack of “global leadership.” Even within NATO, there is growing discord between the USA and the European powers concerning strategy and the question of who is going to pay the bill for imperialism’s security. The EU, which was hailed as a symbol of Europe’s unity, shows signs of disintegration. Brexit is not an isolated example. “EU skeptics” are on the move everywhere, from Italy, France, and Germany to the Netherlands, Denmark, and Hungary.

Future Contradictions

Thirty years of neoliberalism have altered the world balance of power. At first, US hegemony was solid following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, it is challenged in various ways. The center of industrial production has moved to the Global South, predominantly to China. China no longer belongs to the periphery of global capitalism; it has become its motor. The principal contradiction of neoliberalism vs nationalism could “spill over” into the USA vs China as the principal contradiction.

Even if such a rivalry remained a “cold war,” or if armed confrontations remained geographically limited, it would have enormous consequences, as it would entail the danger of nuclear weapons being deployed with catastrophic outcomes.

More nationalist capitalism means imperialism that is strongly based on territorial dominance, akin to the situation before World War I. This is where the USA’s interest in buying Greenland comes from; climate change means that the shipping routes north and south of Greenland will be of great strategic importance. Another example of this trend is that Trump has made “space” itself into a new potential battlefield.

Apart from these major geopolitical confrontations, the world is full of regional conflicts. Parts of the Arab world have been plagued by war for half a century. Whole nations are in ruins, from Iraq and Syria to Libya and Yemen. New wars are on the horizon: Iran vs. USA/Saudi Arabia, USA/EU vs. Russia (primarily over Ukraine and Crimea), the USA vs. North Korea, the powder keg in Afghanistan, and so forth.

On top of all this, there are environmental problems whose consequences become ever more pressing for humanity. The exploitation of raw materials, the depletion of the earth, and the burning of fossil fuels – all to satisfy capitalism’s need for accumulation – steadily sharpened the contradiction throughout the twentieth century. To this day, the USA, Canada, Europe, Japan, and Australia/New Zealand have contributed a total of 61 percent of global carbon emissions; China and India combine for 13 percent; Russia is responsible for 7 percent, and the rest of the world for 15 percent. International shipping and air travel account for the remaining 4 percent. The obvious global inequality becomes even more pronounced if we calculate emissions based on consumption rather than production.[21] China, for example, uses plenty of energy and raw materials, but most of what China produces is consumed in the USA, Europe, and Japan.

Environmental and climate problems are linked to imperialism. The global chains of production transport not only cheap smartphones, T-shirts, and sneakers from the Global South to the Global North. All of these goods entail energy and raw materials. The unequal exchange between the Global South and the Global North is not just economic but ecological as well. With the relocation of industrial production, industrial pollution of land, water, and air has also moved South. Environmental problems cannot be solved independently from imperialism. “Capitalism vs. the earth’s ecosystem” could quite likely be the world’s principal contradiction in the near future. It could take the form of armed confrontations over access to energy, raw materials, and water, “climate migration,” and a further increase in natural disasters as a result of centuries of abuse.

Demands for stronger efforts to combat climate change have been raised worldwide in the past decade, not least among the youth. But even the most radical wings of the climate-justice movement seem to appeal to capitalism’s political institutions, in the apparent belief that they could steer capitalism in a greener direction if they only wanted to. It will be a rude awakening when people realize that the problem cannot be solved within capitalism’s framework. Competition for jobs, greed, and inter-state rivalry make an effective fight against climate change within capitalism impossible.

Along with the late Immanuel Wallerstein, I think that globalized capitalism is in a structural crisis economically, politically, and in its relationship with nature. The system is out of balance, conjunctures do not come in regular waves, but in sudden and uncontrolled swings. For the time being, it seems that the principal contradiction is between a continuation of neoliberal globalization on the one side and different forms of nationalism on the other – the struggle goes on.

I do not think the capitalist mode of production will survive the 21st century. Like other modes of production, it had a beginning and it will have an end. What will replace it is not pre-ordained. It could collapse into a chaos of violent rivalry and ongoing nature catastrophes or it could be replaced by a system based on a more democratic and egalitarian world. In structural crises, it all depends on the “actor” which means our struggle.

There are however some rather unpredictable factors in this transition process, which can complicate the struggle in the coming years: catastrophic impacts of climate change, nuclear warfare, and as we experience now pandemics. They can suddenly enter the scene as a principal contradiction, however, the timing and the global extent of these dangers are unpredictable.

The growing ecological and climatic problems, as well as the scramble for the earth’s natural resources, can trigger revolutionary situations, in the context of sudden changes in living conditions, natural disasters, and refugee flows. A “lifeboat socialism” may well be the only thing that can solve climate change.

The same goes for pandemics, which I consider a special manifestation of the contradiction of capital versus nature. COVID-19 will pass. However, what will be the next pandemic? Furthermore, these kinds of disasters slide into world economic crises.

Finally, there is the danger of nuclear war. The change from neoliberal globalization under US hegemony towards a world of growing nationalism is reflected in increasing rivalry between states, primarily between the United States, China, and Russia. The interstate national rivalry can very well become the principal contradiction in the world. Even if the contradiction between the USA and China remains a “cold war”, possibly with regional “deputy” conventional wars, a growing rivalry can have major consequences. On the one hand, nuclear weapons are essentially defensive weapons; the risk of retaliation, with huge consequences, is high and therefore reduces the likelihood of interstate nuclear wars. On the other hand, the actual use of nuclear weapons is in the hands of individuals and they are not always rational. The struggle for peace, when the ruling class calls for war, is of decisive importance and may have a revolutionary perspective.

This kind of catastrophe will not put a stop to the transition process but will accelerate it and determine its direction. The interactions between global capitalism’s economic contradictions, the political contradictions between neoliberalism and nationalism, and the contradiction between capitalism and the earth’s ecosystem will intensify. Our task is to identify the principal contradiction, intervene in it, and try to resolve it by moving toward a more equal and democratic world. In order to create change, we must mobilize, organize, develop effective practices, and form alliances across social movements and national borders. In short, we need to develop an adequate strategy. We are entering a dramatic and crucial epoch in the history of capitalism, where the contradictions are sharpened and where the outcome of the struggle is not simply about the victory of one class or another, but of the future of humanity and the globe. The outcome will be decided within this century.

Bibliography

Amin, Samir (2010) The Law of worldwide value. Monthly Review Press. New York 2010.

Che Guevara, Ernesto (1966), “Message to the Tricontinental Conference, in January 1966,” Tricontinental Magazine no. 2 April 16, 1967. Havana, Cuba 1967.

Churchill, Winston S. (Author), Langworth, Richard M. (Editor) (2012), Churchill by Himself, Churchill in His Own Words. Ebury, London 2012).

Hobson, John (1902), Imperialism, A study. London: Allen and Unwin, 1948. Luxemburg, Rosa (1951), The Accumulation of Capital. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1951.

Keynes, John Maynard (1936), The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge 1973.

Lenin, V.I. (1914), Conspectus of Hegel´s book: The science on logic. In Collected Works, Vol. 38. Page 85-237. Progress Publisher. Moscow 1968.

Lenin, V.I. (1914), On the Question of Dialectics. In Collected Works, Vol. 38. Page 357-61. Progress Publisher. Moscow 1968.

Lenin V.I (1915), Socialism and war, Chapter I: The Principles of Socialism and the War of 1914–1915 In: Lenin, Collected Works, Volume 21, pages 295-338. Foreign Languages Press, Peking 1970.

Lauesen, Torkil (2020) On the Principal Contradiction. Dialectical Materialism as a Tool for Analysis and Strategy. Kersplebedeb, Montreal, Canada, 2020.

Mao Tse-tung (1928), Why is it that Red Political Power can Exist in China? In Mao: Selected Works vol. I, pages 65-72. Foreign Languages Press, Peking, China.1969

Mao Tse-tung (1937), “On Contradiction. Part IV.” In: Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Volume I. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1969. marxists.org

Mao Tse- tung (1939), The Chinese Revolution and the Chinese Communist Party, Selected Works, vol. II. Foreign Languages Press, Peking, China 1969.

Mao Tse-tung (1949), “Farewell, Leighton Stuart.” In Mao: Selected Works, Vol. IV. Foreign Languages Press, Peking.1969.

Marx, Karl (1848), “The Communist Manifesto”. In: Marx/Engels Selected Works, Volume I, page 98–137. Progress Publishers, Moscow 1969. marxists.org