An evaluation of:

“Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine”

by

Torkil Lauesen

My perspective

I am well aware that it is easier to criticize and offer advice writing from a desk, safely located in Copenhagen, than it is when you are taking part in the struggle in the Middle East. I do not feel the oppression. I do not live in a war zone, where I have to worry about my safety, how to get a roof over my head, or where my next meal is coming from. However, I have been a supporter of the Palestinian liberation struggle for half a century and have followed its development over the years. The declining influence – let us be frank, the crisis – of the Palestinian Left worries me. My intention is not to point fingers or assign blame for “mistakes”. Much of the cause for the decline of the Palestinian Left is to be found in global trends beyond the responsibility of individuals.

In the 1970s and 80s, I visited Lebanon and Syria as a member of the Communist Working Circle and discussed the situation with members of the PFLP. The Communist Working Circle’s praxis was to provide material support to liberations movement by both legal and illegal means.[1] When I sometimes write “we” in this text, it is a reference to my old organization.

Furthermore, I am not Palestinian; I write from the perspective of an international communist. For me, the socialist perspective of the struggle is more important than establishing a national state, regardless of its nature. The decolonization and establishment of new national states in the Third World in the 1950s and 60s was, in most cases, just a prelude to new forms of imperialist exploitation and oppression. Even worse, if the result of a national struggle would be an Islamic Palestinian state, then this state would be my enemy. For Islamists, communists can only be temporary useful idiots, to be gotten rid of once you are in power.

This is a text about strategy. Political practice is often the result of rather spontaneous reactions to economic hardship and social oppression. But without a proper analysis of the world we live in and an adequate strategy, one’s political practice is unlikely to bring about change. Analysis requires a constant back and forth between empirical study and theoretical reflection. Strategy requires a constant back and forth between the results of our analysis and their practical application.

There have been numerous Intifadas and uprisings over the past fifty years –which all petered out in the end. The Palestinian masses have risen up in anger and desperation against oppression and the material conditions of life under occupation. The problem has been developing a strategy that can transform this revolutionary energy into change. There has been an intense and ongoing debate on the Palestinian Left over the past fifty years, as to the strategy for liberation. However, no strategy has succeeded in bringing about liberation.

This text is also about method. It is important to be conscious of what method we use to interpret the world. What we see depends to a large extent on the glasses we wear. I do not have the detailed information and knowledge about the situation in Palestine that one can acquire living in the region and participating in the day-to-day struggle. Instead, I look for answers by lifting my eyes from internal Palestinian affairs to the global perspective. What is the principal contradiction on the global level? How does it relate to contradictions on the regional and national levels? Can we change, or at least influence, such factors in a direction that can advance the struggle in Palestine?

My safe and far-away position allows me to take a longer and global perspective on the Palestinian struggle. Intense conflict often makes immediate local contradictions the most important for the participants. Yet the outcome of these struggles often depends on global contradictions. An effective strategy requires a specific analysis of the local actors within the regional and global framework.

The development of strategy is a collective task, one which requires reflection and discussion. This also applies to this contribution. I am thankful for all the comments I have received on draft versions of this text.

In the first part of the article, I will look at the PFLP’s 1969 program, Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine, examining it in a global perspective. What were the international conditions for the emergence of the program? How was the strategy implemented, and with what results? In the second part of the article, I will examine the current global contradictions, which set the scene for the Palestinian struggle. What do these contradictions imply for the development of a strategy for the liberation of Palestine?

Part 1

The PFLP in the revolutionary wave of “The Long Sixties”

In 1956, at its 20th congress, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union did away with its Stalinist past, but it also lost much of its former revolutionary spirit. By embracing peaceful coexistence, the Soviet Union chose to compete with the capitalist system on its terms, instead of pursuing a qualitatively different road and the promotion of extending the socialist world revolution.

The consequence of a full-scale nuclear war during the “Cold War” would have been the end of the world as we know it – and such a catastrophic event was a real possibility, as the historical record has shown. In that sense, the Soviet policy may have saved the world millions of casualties and a devastating nuclear winter.

However, that is another story. The main point here is that the revolutionary spirit did not vanish, it just moved to The Third World, where imperialist and colonialist exploitation and oppression made rebellion imperative. Throughout the ’60s and into the early ’70s, with its zenith in the 1968 uprising, a revolutionary wave washed over the world.

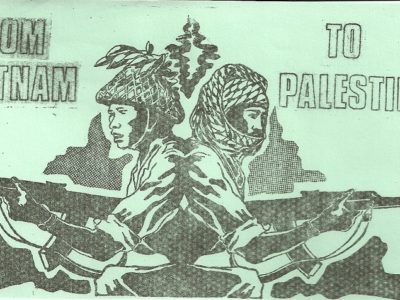

The struggle against colonialism and imperialism had been a significant force since the end of the Second World War. The Chinese communists proclaimed the People’s Republic in 1949, the Vietnamese defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the Cuban revolution prevailed in 1959, and the Algerian war of liberation against France was victorious in 1962. For the first time, the Third World came together in a conference in Bandung in 1955, manifesting a new unity. In these post-colonial societies, the revolutionary spirit continued to be high. The Chinese, the Cubans, and the Algerians supported new revolutionary movements in Africa, Asia, and Latin America – the movements of the three continents. Up through the ’60s, there was a new wave consisting of around forty powerful revolutionary socialist movements, which challenged imperialism from Vietnam to Palestine to Angola, from Mozambique to Chile. If one had put red pins on a world map to mark these struggles in 1968, the future for a socialist world revolution would have looked bright. It was in this context that Che Guevara declared that we must create:

“…the Second and Third Vietnam of the world. We must bear in mind that imperialism is a world system, the last stage of capitalism — and it must be defeated in a world confrontation.”[2]

I will assert that in the decade from 1965-75, the principal contradiction on the world level was between imperialism, led by the US, and the numerous anti-imperialist movements and progressive Third World states that were trying to build socialism. The guerrilla fighter was the new revolutionary subject. From revolutionary practice, theory itself was being generated in the Third World, by Mao, Ho Chi Minh, Guevara, Fanon, Cabral, and others.

The Chinese Cultural Revolution of 1965-69 was a part of this new revolutionary spirit. China itself was in a revolutionary tumult. Mao said, “It is right to rebel” and called on the masses to “bombard the headquarters”. The Chinese Cultural Revolution also had a global dimension. The Chinese Communist Party promoted people’s war in the global countryside to encircle the imperialist metropoles. China’s attempt to combat bureaucratization and thereby renew the construction of socialism, and its uncompromising attitude toward imperialism, were an inspiration for revolutionary movements around the world. The global revolutionary spirit and the success of the Vietnamese struggle also ignited a new wave of militant struggle with a socialist perspective in Palestine.

This new movement had its roots in the pan-Arab nationalist movement of the ’50s, which was generated by a century of European colonialism and, to top it all off, the proclamation of the Israeli settler state in 1948. The class foundations of the movement were the petit bourgeoisie, young military officers, and other educated technicians and teachers. They were not communists but had a strong desire for national development independent of imperialism. In 1952, Gamal Abd al-Nasser came to power in a military coup in Egypt, Abd al-Karim Qasim became president in Iraq in 1958 by similar means, and the Ba’ath Party came to power in Syria that same year. They all pursued the creation of secular states in opposition to conservative Islam and shared a dream of Arab unity from the Persian Gulf across North Africa to Morocco.

The roots of the PFLP

A Lebanese offshoot of this political trend was the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), founded by George Habash and Wadi Haddad while the two were studying medicine in Beirut in 1955. The aim was to create a united Arab nation in line with Gamal Nasser’s thinking. The ANM managed to establish small sections in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, South Yemen, Egypt, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Libya. After finishing their studies, Habash and Haddad moved to Jordan to work in the Palestinian refugee camps there, both as doctors and politically. At the beginning of the 60s this Palestinian section of the ANM, which turned out to be the only viable section, began to change. In 1964, the ANM decided that socialism should be the guiding line for the movement and armed struggle part of its praxis. In 1966, the ANM established its first guerrilla group, called “The Heroes of Return”.

The June war in 1967, in which Israel defeated the surrounding Arab countries and occupied the West Bank of the Jordan River, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai desert, became a turning point in the history of the Palestinian resistance. It became clear that the Arab nationalist regimes and their conventional warfare strategy were not capable of liberating Palestine and securing the return of the refugees.

The Israeli settler state was of quite another caliber than the French settler state in Algeria. The Israeli settlers were dedicated, determined, and equipped with sophisticated weapons, and they had the full support of the US. The strategy of the Pan-Arab nationalist movement was in crisis; from 1968, the ANM ceased to really exist. However, the mood was not one of resignation. On the contrary, the revolutionary “spirit of ’68” was all about taking matters into our own hands. On the ruins of Pan-Arab nationalism, new revolutionary movements were founded by adding Marxism and guerrilla warfare to the strategy.

Habash and his comrades from the ANM united a handful of the new organizations that had emerged in the wake of the Six-Day War, establishing the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) on December 11, 1967. Yasser Arafat’s Al Fatah declined an invitation to join, as they had their own plans to lead the struggle within the overall framework of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Al Fatah wanted to include progressive forms of Islam, similar to what had occurred in the Algerian liberation struggle. Al Fatah was not Marxist but was a broad nationalist organization with many different factions, ranging from Maoist sympathizers to Nasserists, all held together by the charismatic Yasser Arafat.

In autumn 1969 the PFLP was a rather broad Marxist organization inspired by the “New Left” of ’68 and with sympathies for Maoism, especially the idea of Protracted People’s War. George Habash visited Beijing in the autumn of 1970; however, the only material support the PFLP received from China was a bag full of copies of Mao’s Little Red Book. Habash later traveled to Moscow where he met with more success in terms of promises of material support. The PFLP was also inspired by Che Guevara’s “foco theory”, according to which the party is simultaneously both a military and a political organization, with the guerilla struggle creating a focus, which then mobilizes the masses.

From the start, the history of the PFLP was full of internal struggles over ideology and strategy. While Habash was imprisoned by the Syrian government, charged for sabotage of the Trans-Arabian oil pipeline running through Syria, a faction lead by Hawatmeh called for a conference in August 1968, which adopted a statement with harsh criticisms of Nasserism and proclaimed that proletarian revolution was the road to the liberation of Palestine. Habash was liberated from prison by a daring action by Waddi Haddad and escaped to Jordan, where he resumed the struggle for the leadership and the political line of the PFLP.

The conflict ended with a split in which the minority Hawatmeh faction left to form the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DPFLP) in February 1969. The main disagreement concerned the role of the petit bourgeoisie, both in terms of the character of the neighboring Arab regimes Syria and Egypt and in terms of the Palestinian petit bourgeoisie. The DPLFP thought that the PFLP was too preoccupied with cooperation with petit bourgeois elements to be able to develop into a proper Marxist-Leninist organization. The PFLP for their part, borrowing from Lenin, labeled the DPFLP an “infantile left-wing disorder”.

This was not the only split, however. In October 1968, the Palestine Liberation Front (PLF), under the leadership of Ahmed Jibril, left the PFLP to form the PFLP-General Command. Jibril was tired of all the ideological discussions; the PLF’s focus was on national unity and armed struggle here and now.

Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine

As a result, there were fierce debates in the organization leading up to its Second Congress in February 1969. The congress ended with the adoption of Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine.[3] The congress also buried the idea of the PFLP being a broad national front – although the name was maintained – instead, the aim was to build a Marxist-Leninist communist party.

The Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine document was influenced by the younger generation attracted to the PFLP in the late ’60s, among them its spokesperson Ghassan Kanafani. The document was groundbreaking in the Middle East context at the time. It not only presented a radical alternative to Arab Nationalism, Western-style liberalism, and political Islam, but also to the traditional Arab communist parties, which were linked to Soviet Marxist orthodoxy, which at the time prescribed that “backwards” Third World countries had to go through a national capitalist period before socialism could be developed.

The title of the first section is “Importance of Political Thought”. The program is explicitly socialist in its discourse; the categories and concepts employed and its method of analysis are Marxist. The Palestinian struggle is seen as part of a global struggle for socialism. It is not just a struggle for a national state, which might as well be a petit-bourgeois, bourgeois, or an Islamic project. No, the goal is also a social revolution led by the working class and peasantry.

The title of the following section is “Who are Our Enemies?”, reflecting Mao’s influence:

Who are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance of the revolution. The basic reason why all previous revolutionary struggles in China achieved so little was their failure to unite with real friends in order to attack real enemies.” [4]

Who are Our Enemies?

The Israeli settler-state

In the struggle for the liberation of Palestine, the immediate enemy is the Israeli colonial settler-state and the Zionist movement. Settler colonialism originated in 19th century Europe. The settlers were often “surplus” labor from the countryside, people who could not find work in the cities and tried to find a way to make a living by emigrating to the European colonies. Emigration was a safety valve alleviating social unrest in Europe. Emigration reduced the size of the “reserve army of labor” in Europe, thus securing the remaining workers a better position in the struggle for higher wages. There are different kinds of settler colonies. There is the type in which the settlers constitute an upper class that exploits the indigenous population; examples include Algeria, South Africa, and Rhodesia. In another type of settler colonialism, the original population is displaced or more or less eradicated and the settlers grab the land and thus constitute the majority of the population; examples include the USA, Australia, New Zealand, and Israel.

Settlers claimed land and resources, displacing and dispossessing the original population in bloody conflicts. This created a racist hierarchy, embedded in the foundations of the settler-state, which positioned immigrants from North-Western Europe as an upper layer of the population. In North America, European settlers could climb up the class ladder by acquiring a share of the profits from land privatization and speculation and the benefits from the exploitation of the local population, slaves, and immigrants from Asia. The same racist ideology of white supremacy gradually took shape in Israel, penetrating the Middle East as an offspring of European and North American culture. Just as the emigrants from Western Europe were turned into racist settlers by the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, persecuted European Jews were turned into racist settlers through immigration to Israel and the expulsion of the Palestinian population. Israel was God’s own land to be ruled by his chosen people. In that sense, Israel shares many similarities with the former Boer apartheid state in South Africa. Racism and religious chauvinism blocked the development of any solidarity based on class consciousness between emigrant workers and peasants and the local population. The Israeli settler-state assumed some aspects of a “First World” character, in terms of culture and living standards, in a Third World region.

The Israeli settler-state was constituted under very special circumstances. Emigration to Israel was not primarily grounded in lack of work and poverty, as had been the case in emigration to North America in the 19th century. Emigration to Israel was the product of centuries of European antisemitism, which had culminated in the Nazi Holocaust. To solve this European problem, Zionism proposed establishing a nation-state for the Jews in Palestine, to be called Israel. What turned this idea into reality, however, was the support of the USA, the Soviet Union, and the majority of the European states in the wake of the Second World War. The settlers came from all sectors and classes. This common fate of the Jews during the war, across class lines, gave the new state a particular internal strength.

It is worth keeping in mind that the establishment of Israel had its origin in contradictions within Europe and the outcome of the Second World War, and not in contradictions in the Middle Eastern region.

From its birth, Israel was a “garrison state”. Old and young, men and women alike – all were drafted into the army. The civilian populations in the settlements were armed and part of an organized security force. As the Second World War came to an end, the Zionist movement managed to acquire some of the surplus weaponry. Soon after it was established, Israel developed an important advanced weapons industry. What it could not produce itself was delivered by the USA. Israel became the strongest military power in the region, possessing a fleet of fighter jets, advanced missile systems, and even nuclear arms. Today Israel is known as a pioneer in the use of new military and intelligence equipment, such as drones and surveillance equipment. The production and sales of arms and all kinds of security expertise and services has been an important part of Israel’s economy and foreign policy from the foundation of the state.[5] Israel has 1,600 licensed arms exporters, which employ 150,000 to 200,000 people. In addition, there is a large supply chain of subcontractors who provide software and other parts necessary for arms production. For example, Israel delivered arms to South Africa when all other states boycotted the apartheid regime. The Israeli weapons industry markets its products as “battle-tested”, meaning that they have been tested for effectiveness on Palestinians.

Zionism

There is irony and tragedy in the fact that one persecuted group of people – the Jews – has ended up expelling and oppressing another group of people – the Palestinians. The problem occurred when Zionism entered the Jewish community in Europe at the end of the 19th century. The Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) is considered the founder of Zionism. He saw the establishment of a settler state in Palestine as the solution to the persecution of Jews, in line with the colonial thinking in Europe at the time. Chaim Weizmann, later president of the World Zionist Organization and later still the first president of the State of Israel, told a Berlin audience in March 1912:

“Each country can absorb only a limited number of Jews if she doesn’t want disorders in her stomach. Germany already has too many Jews”.[6]

Prior to the 1930s, Zionism did not enjoy much support among European Jews. Religious leaders were skeptical because Zionism would subordinate religion to an alleged national unity. Others saw emigration as giving in to the rampant antisemitism in Europe. However, the intensified antisemitism in Europe up through the 30s caused a gradual change in attitudes amongst some Jews, as they did not get much support from the European population or state authorities against this racism. Outside of Jewish circles, the Zionist settler project did not have much support before the war. The colonial master in Palestine at the time, Britain, was not against Zionist settlement, but was opposed to the idea that all of Palestine should become a Zionist state. It was only when the Holocaust was revealed in the spring of 1945 that sympathies for the Jews, and guilty consciences, turned into support for the establishment of the Israeli state. Israel is, in its own peculiar way, a colony created by the darkest chapter of European history – Nazism. As an anachronism, Israel became the last European settler-colonial project, in an era when decolonization was on the agenda.

Zionism is still an important movement. In the USA, the Zionist lobby is an important factor in creating political, economic, and military support for Israel.

The fact that European antisemitism was the driving force behind the establishment of Israel, is used cynically by Zionism to label any criticism of the settler-sate as antisemitic. The sympathies for the tragic fate of the Jews in Europe during the war are still immensely significant for support for Israel. Therefore, criticism of Zionism from persons of Jewish descent is of great significance. Such people are courageously standing up to the pressure from their surroundings and are risking social exclusion, and as such should have our support.

Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine is well aware of this problem. In the chapter “The Aim of the Struggle”, the PFLP’s position is clear. Two paragraphs in particular merit being quoted in full:

“The Palestinian liberation movement is not a racial movement with aggressive intentions against the Jews. It is not directed against the Jews. Its object is to destroy the state of Israel as a military, political and economic establishment which rests on aggression, expansion and organic connection with imperialist interests in our homeland. It is against Zionism as an aggressive racial movement connected with imperialism which has exploited the sufferings of the Jews as a stepping stone for the promotion of its interests and the interests of imperialism in this part of the world which possesses rich resources and provides a bridgehead into the countries of Africa and Asia. The aim of the Palestinian liberation movement is to establish a democratic national state in Palestine in which both Arabs and Jews will live as citizens with equal rights and obligations and which will constitute an integral part of the progressive democratic Arab national presence living peacefully with all forces of progress in the world. Israel has insisted on portraying our war against it as a racial war aiming at eliminating every Jewish citizen and throwing him into the sea. The purpose behind this is to mobilize all Jews for a life-or-death struggle. Consequently, a basic strategic line in our war with Israel must aim at unveiling this misrepresentation, addressing the exploited and misled Jewish masses and revealing the conflict between these masses’ interest in living peacefully and the interests of the Zionist movement and the forces controlling the state of Israel. It is this strategic line which will ensure for us the isolation of the fascist clique in Israel from all the forces of progress in the world. It will also ensure for us, with the growth of the armed struggle for liberation and clarification of its identity, the widening of the conflict existing objectively between Israel and the Zionist movement on the one hand and the millions of misled and exploited Jews on the other.

The Palestinian liberation movement is a progressive national movement against the forces of aggression and imperialism. The fact that imperialist interests are linked with the existence of Israel will make of our struggle against Israel a struggle against imperialism, and the linking of the Palestinian liberation movement with the Arab liberation movement will make our struggle against Israel the struggle of one hundred million Arabs in their united national effort for liberation. The struggle for Palestine today, and all the objective circumstances attendant upon it, will make of this struggle an introduction for the realisation of all the aims of the Arab revolution which are linked together. It is a wide and vast historical-movement launched by one hundred million Arabs in a large area of the world against the forces of evil, aggression and exploitation represented by neo-colonialism and imperialism in this epoch of human history”[7]

It is of the utmost importance to keep this goal in mind: The struggle is for a secular state in Palestine, with equal rights for all, regardless of ethnic background or religion.

Imperialism[8]

The State of Israel is a distinct settler-colonial project with its own interests, while at the same time it serves a certain purpose for US imperialism. The founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, in 1896 was already writing in The Jewish State of playing this role vis à vis the the Ottoman Empire.

“There (in Palestine) we shall be a sector of the wall of Europe against Asia, we shall serve as the outpost of civilization against barbarism.”[9]

A way of thinking that parallels the American discourse about the “clash of civilizations”. A Western “Judeo-Christian” culture battling “Arab/Muslim international terrorism”. As such, the importance of the struggle for Palestine extends beyond its small geographic area and limited economic significance. The national struggle for an independent Palestinian state has a high symbolic value in the Arab world.

However, on the side of Israel stands imperialism – mainly the US, which through its support for Israel sustains its economic, political, and military interests in the Arab world. Israel serves as a “US battleship” situated in the landmass of the Middle East. It secures US interests in the vast oil resources in the region. Cheap oil was the energy resource that fueled the post-war development of capitalism. Furthermore, the Middle East is of geopolitical importance as the gateway between Asia and Europe. As Asia became the “factory of the world” over the past fifty years, the Middle East was turned into a permanent war zone to secure US global hegemony. The importance of geopolitical control of the region became obvious when the Suez Canal was blocked for six days in March 2021 when the Evergreen container ship ran aground. The disruption to global trade for only a short period had huge consequences for the supply of industrial goods from Asia.

Arab reactionaries

In its efforts to maintain control over the region, the USA also relies on the reactionary Arab states. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, all of which border the Persian Gulf, have served this role with increasing importance. As early as the mid-19th century, the industrialization of the imperialist center relied on the flow of cheap oil from the Middle East. It was first secured by the British Empire and after the Second World War by the US. “The Seven sisters” – Esso, Shell, BP, Mobil, Texaco, Chevron, and Gulf – ran the wells and got the profits. However, in the late 60s and 70s, in the context of the wave of Third World nationalism, the ruling elites of the Gulf State monarchies managed to win a significant portion of the oil revenues for themselves. This revenue increased significantly with the establishment of OPEC, which doubled the price of oil. For a short period, OPEC even played a progressive political role, supporting the Arab countries in their wars with Israel, by enforcing an oil embargo and raising oil prices. All this changed in the mid-70s. Oil revenues created a market for consumer goods in the region, especially luxury products. However, most of the revenues were invested in Europe and North America in everything from Mercedes to football clubs, which linked the interests of the Gulf States to the interests of imperialism. Later, the oil revenues were invested in opulent city development, constructed by importing cheap labor on contract from Bangladesh, Nepal, and the Philippines. Cities like Dubai have attracted wealthy people, often with shady backgrounds. The Gulf States have become an important hub for air transport of passengers and goods, both between the West and East and between the West and Africa. They have also invested in the tourist industry and have attracted major sports events to improve their image. Even though the oil money seems to have corrupted any opposition, the stability of Saudi Arabia has occasionally been threatened by contradictions between different factions of the royal family.

In spite of Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf States’ conservative Islamism, the USA and European arms producers have equipped them with the latest weaponry, in order to secure control of the Strait of Hormuz and put pressure on Iran.

In conclusion, in the battle for the liberation of Palestine, the immediate enemy is the Israeli colonial settler state and the Zionist movement. However, behind Israel stands imperialism – first and foremost the US, which through its support for Israel sustains its economic and political control of the Arab world. To this end imperialism also relies on the reactionary Arab states. The conclusion of the 1969 program, that “Our enemy in the battle is Israel, Zionism, world imperialism and Arab reactionaries” (p.38), remains true today.

Class Analysis

The next step in developing strategy is to determine who our friends are – the forces of revolution. According to conventional Marxism, the workers and peasants are defined as the main force of the revolution, its material basis, and its leadership. However, there is no specific description of the character and composition of the working class and peasantry in the 1969 program. What is the type and size of the different kinds of wage labor? How are the workers organized? What are the property relations in the agricultural sector? What is the role of wage labor in the agricultural sector? An abstract class analysis full of generalizations is difficult to translate into strategy and praxis. I am not able to present a useful class analysis here. What follows are some tentative preliminary remarks to such a future thorough class analysis.

The bourgeoisie

The Palestinian bourgeoisie is rather insignificant. Following 1948, many Palestinian capitalists moved, initially to Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt, and then later some became wealthy businessmen in the Gulf countries.

The Palestinian economy is integrated and dependent upon the Israeli economy. Israel has complete control over all external borders. Approximately 75 percent of all imports to the West Bank and Gaza originate in Israel and 95 percent of its exports are to Israel. This makes the development of an independent Palestinian bourgeoisie impossible. It is comprador in nature. The defining feature of the Palestinian bourgeoisie is its relationship to Israeli capital. Since the Oslo Accords in 1993, this bourgeoisie has fused with sections of the PA bureaucracy, forming a major pillar of its rule.

The Petit Bourgeoisie

The petit bourgeoisie is a more interesting class; historically, it has played a significant role, both in Palestine and in the surrounding Arab states. The petit bourgeoisie comprises artisans, students, teachers, junior employees, small shopkeepers, lawyers, engineers, medical staff, and various kinds of academics. Palestinians are well educated compared to citizens of other Arab countries. If you look at the class background of the leadership of revolutionary movements in general, you will see that the petit bourgeoisie is well represented. This is also true of the PFLP; Habash and Haddad were doctors, Kanafani was a journalist, and Ahmed Sadat is a teacher.

As a class, the petit bourgeoisie does not have an objective material interest in revolution. It shifts sides between the bourgeoisie and proletariat, both in terms of its living conditions and politics. It can be an ally to the forces of revolution during the stage of national liberation, but it can also turn against it. The relationship with the petit bourgeoisie as a class can be difficult and should be treated with care. This dilemma is discussed in detail in the 1969 program, as the petit bourgeoisie was leading the PLO and many Arab states in the late ’60s.

The vacillating character of the petit bourgeoisie has been revealed in developments in the Arab world since that time. In 1969 regimes like Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Libya, and Algeria were progressive, both in terms of national economic development and foreign policy, including support for liberation movements. However, from the late ’70s and up through the ’80s, their attempts to pursue national economic development independent of imperialism and for the benefit of the broad masses were penetrated by the global neoliberal offensive. The petit bourgeois national project was not rooted strongly enough in the popular masses to withstand the pressure from the surrounding capitalist world economy and the demands for structural adjustment from the IMF and the World Bank. They opened up their economies to neoliberal market forces, privatized the state-owned sector, shut down state subsidies for national industry, and cut back state welfare programs. As these developments led to a decrease in popular support, turning into opposition, the formerly progressive regimes became more and more despotic to retain power. I remember in the mid-’80s how my Palestinian friends in Damascus would look over their shoulders whenever our discussions turned to the situation in Syria.

The Working Class

This relationship between the Palestinian areas and the Israeli economy, along with the comprador nature of the Palestinian capitalist class, has divided the Palestinian workforce in three: workers in Israel and the settlements, employees in the PA public sector, and a private sector dominated by small businesses. There is virtually no industrial working class as such.

Israel has consciously delinked itself from any reliance on cheap Palestinian labor, replacing it with foreign workers from Asia and Eastern Europe. Reducing the Palestinian labor force in Israel to a second reserve army of labor alongside foreign workers.

Since the Oslo Accords, employment in the public sector has grown. The PA accounts for nearly 25 percent of employment in the local economy. Financed by foreign institutions, more than half of the PA’s budget is spent on public sector wages.

The private sector is dominated by small family-owned businesses. Over 90 percent of Palestinian private sector businesses employ less than ten people. The Palestinian territories lack any significant large industry. The structure of the Palestinian working class has implications in terms of political strategy. There is no large organized labor movement with sufficient economic weight to be a driving force in the struggle; this is unlike what had been the situation in the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, where the trade unions, particularly the mineworkers’ union, played such an important role.[10]

The Lumpen Proletariat

One class that is completely absent from Strategy for the liberation of Palestine – as in so many other class analyses – is the lumpen proletariat. This class has a significant size, especially in Gaza and in the refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. However, the omission is not surprising, as traditional Marxism has treated the lumpen proletariat with suspicion and sometimes contempt. Its contribution to the revolutionary process has been marginalized in much Marxist literature.

In textbook Marxism, we learn that class position is determined by people’s function in the sphere of economic production and distribution. But that is not the only way classes are formed in real existing capitalism.[11] Capitalism can give birth to classes by criminalizing and repressing them out of their old traditional socio-economic roles, or by destroying their basis of existence by war and expulsion, as in the case of the Palestinians. The lumpen proletariat is a growing class in North Africa and the Middle East in general, as people are separated from the land, unable to sustain themselves or find wage labor. This was made clear in the refugee crises in 2016, when millions migrated from war and poverty across the Mediterranean toward Fortress Europe and in caravans from South and Central America toward the US border on the Rio Grande.

The lumpen proletariat consists of people without a steady relation to the labor market. Unemployed people who live on casual work and are often supported by friends, family, and charity. It can include homeless people, beggars, petty criminals, gang members in organized crime, and sex-workers. In general, traditional Marxism has a negative attitude towards the lumpen proletariat.[12] The claim is that they lack a clear class position towards capitalism and are more apt to be mobilized by reactionary forces. However, if you look carefully into the history of uprisings, you will see that the lumpen proletariat has often been an important factor in the revolutionary process. This was the case in the first communist revolutionary attempt, the Paris Commune in 1870; however, one of the most important examples is the Chinese revolution. Mao wrote in his concise class analysis of Chinese society in 1926:

“Apart from all these, there is the fairly large lumpen-proletariat, made up of peasants who have lost their land and handicraftsmen who cannot get work. They lead the most precarious existence of all…. One of China’s difficult problems is how to handle these people. Brave fighters but apt to be destructive, they can become a revolutionary force if given proper guidance.”[13]

In China, the lumpen proletariat consisted of landless peasants, criminals from China’s many organized gangs, beggars, prostitutes, homeless, and wandering mercenaries. Mao knew these groups very well. In 1929, he stated, “that the lumpen proletariat constitutes the majority of the Red Army”, which was also scornfully called the “vagabond army” by the Kuomintang.[14] The lumpen brought combat experience and tactical knowledge from their gang activity, as well as an extreme toughness, to the Red Army. Here they were met with acceptance instead of prejudice. Several former gang members rose quickly to high ranks in the Red Army. A more recent example is the Black Panthers in the US in the late 60s, which was essentially an organization of lumpens who became revolutionary.

In a Middle East context, we have seen Islamic forces recruiting many fighters from this stratum, but the left has lacked a class analysis and an approach for mobilizing the lumpen proletariat.

The Palestinian Diaspora

Another group in need of a more thorough analysis is Palestinians in the diaspora. It is estimated that more than 6 million Palestinians live in a global diaspora. More Palestinians live outside of Palestine than in it. The diaspora can be divided into several categories. The ones living in the refugee settlements in neighboring countries: in Jordan 3.25 million, Lebanon 0.5 million, and Syria 0.6 million. Those working in the Gulf States, but who have some kind of base in Palestine or the surrounding countries. The Palestinians who have emigrated are in another category. There are Palestinians worldwide, especially in Latin America. Chile alone has 500,000, the largest Palestinian community outside of the Middle East. In Europe, Berlin alone hosts about 40,000 people of Palestinian origin.

People in these categories live under very different circumstances, belong to different classes, and have different hopes for their future life. Palestinians in Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan are in a difficult position. They are not fully accepted as citizens by their host countries, are often unemployed, and do not have access to a steady income. Most are born outside of Palestine and are second or third-generation refugees. Some see their future in their host country; others hope to return to Palestine. But how and when? Fundamental social issues affecting the Palestinian population in the diaspora have been neglected since the mid-’80s and they are kept marginalized from positions of influence in the organizational structure of the resistance.

The immigrants in North and South America and Europe still retain their Palestinian identity and still have family in Palestine or the neighboring countries; however, on a personal level, for most of them, their interest is in integrating into their new home country. Again, they have to be analyzed in terms of class position. However, many of them can still be mobilized to support the struggle, both materially and politically. They can be part of the international struggle against the apartheid state, for instance in the campaign to boycott goods produced in Israel, and the sports, cultural, and academic boycott of Israel. It is important that Palestinians in diaspora reach out to local left-wing groups in that endeavor. A mixed movement has a much greater potential.

In conclusion, there is a need to develop a specific class analysis of the Palestinian people. It is not enough to operate with abstract and general categories such as bourgeoisie, petit-bourgeoisie, workers, and peasants. To be useful in developing a strategy the analysis has to be specific and detailed. What is the potential of each class strata and how can this be used in the struggle.

We cannot limit our analysis to abstract definitions of classes. There are huge differences between the working classes of Germany, China, and Palestine. Differences we can only understand through a specific analysis of each society’s particular contradictions. As Mao did in China, we must study our own society at the particular stage of development we find it in. If we are content with only distilling commonalities, we won’t get any further than finding that, in terms of class, the principal contradiction in a capitalist society is that between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. To limit ourselves to defining common features and neglecting the study of the particular is what Mao called “theoretical laziness.”

The forces of revolution

Internationalism

From class analysis, Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine moves on to more specific strategies in the struggle. The first principle is “Internationalism”:

“The Palestinian revolution which is fused together with the Arab revolution and in alliance with world revolution is alone capable of achieving victory. To confine the Palestinian revolution within the limits of the Palestinian people would mean failure, if we remember the nature of the enemy alliance which we are facing.” (pp. 66-67)

“Internationalism” is not just a word to invoke when making a toast at a celebration, but is a practical strategic priority. The possibility of a successful and stable transition towards socialism will be limited if it only takes place in one country or global region. There has not been a socialist country, at any point in time. Not in the Soviet Union or China or elsewhere. A genuine and comprehensive transition from capitalism to socialism must involve the world majority. Capitalism is a global system and whenever any nation-state has attempted to escape from it, they have immediately been confronted economically, politically, and militarily by the surrounding dominant capitalist powers.

However, the road towards global socialism passes necessarily through national struggles. The national state is still the primary political framework in the world system. But any national struggle has to be fought with a clear understanding of the global perspective, therefore prioritizing internationalism, both in terms of economic and political cooperation. There have been many attempts to build socialism in the past. Their failure does not necessarily mean that the strategies were wrong, that the attempts were fruitless, or that the mission as such is impossible. The transition from capitalism to socialism is a long ongoing historical process of experiments, learning, and perseverance, as the capitalist mode of production runs out of options and enters into decline. We are approaching this phase.

Many liberations movements try hard to attract international support to their struggle but are less good at prioritizing practical international cooperation with other liberations movements. However, the PFLP has tried its best to practice real “internationalism”. It was in the DNA of the PFLP, a legacy of the ANM’s explicit pan-Arab goals. This was strengthened by the inspiration of Che Guevara and was put into practice in the camps in Lebanon.

We, in the Communist Working Circle in Denmark, did not support the PFLP primarily because it aimed to establish a Palestinian nation-state, but rather because the PFLP envisioned a socialist Arab world. In general, the PFLP had a strong internationalist outlook. It allowed liberation movements from around the world to use its facilities. The first FSLN guerrilla fighters, the Nicaraguan Sandinistas, were trained in a PFLP camp in Lebanon. During our visits, we saw Kurds, Turks, Iranians, South Africans, and Nicaraguans in PFLP camps. In other words, to support the PFLP was to support many liberation movements. This possibility of being an international revolutionary force was however severely limited by the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and the expulsion of the Palestinian organizations to Tunis and Syria.

National Unity

The establishment of national unity in the struggle has traditionally been a priority for liberation movements. However, the question of unity raises two questions: What should be the basis for this unity? And who should be the leading force in national unity? These questions have led the PFLP to change its practical position toward unity several times over the past fifty years, as different proposals for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have been accepted by the PLO. At times, the PFLP has established a “rejectionist front” towards the majority in the PLO. At times, they have expressed criticism but remained within PLO. The PFLP has never been in a position to lead the struggle. In the ’70s and the first years of the ’80s, the Palestinian Left constituted a significant opposition to Fatah’s dominant position in the PLO. However, with the move from Lebanon to Syria, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the general crisis of socialism, the PFLP lost much of its power base. As a result, the PFLP became more traditional nationalists in an attempt to muddle through these difficult times. To sustain the organization, they became more dependent on support from NGOs and the crumbs from the PLO. They became less the radical uncompromising socialist alternative to political Islam (in the form of Hamas), or to national liberalism (in the form of Fatah and its dominant position in the “Palestine National Authority” (PA) on the West Bank). Hamas had a growing influence, especially in Gaza, by virtue of the resources it provided to meet people’s immediate needs in terms of food, healthcare, etc. The PA could provide jobs.

National unity became the priority, at the expense of the ideas of socialism and a secular state, The PFLP has more or less stopped addressing labor issues, widespread youth unemployment and growing poverty, and the question of women’s rights in its political proposals.

When the left seeks national unity from a weak position, it risks becoming just the wagging tail of a dominant conservative nationalism. It is becoming more and more difficult to defend the dysfunctional institutional frameworks of the PLO, thus protracting the current crisis of the Palestinian socialist movement.

Military Strategy

The chapter “Facing Imperialist Technological Superiority” (p. 95) deals with military strategy against the superior Israeli military force. This superiority is expressed in the high standard of training and motivation of the soldiers, the high quality of its military leadership, and its overall superiority in arms and other military equipment. The Israeli victories over the Arab states in the wars of 1948, ’56, ’67, and ’73 are an expression of the strength of the Israeli army in conventional warfare.

The 1967 defeat was a wake-up call for the Palestinian resistance. They realized that the enemy could not be defeated in a conventional war waged by Egypt and Syria. To counter the Israeli superiority, people’s war and guerrilla strategy had to be implemented. This strategy had proven effective in China, Vietnam, and Cuba, and had been adopted by other liberation struggles in Africa and Latin America at the time. Ho Chi Minh’s claim, that the human factor – revolutionary determination – was more important than military technology, seemed to be have proven correct in Vietnam. However, there is also another “human factor” – both the Vietnam war and the Algerian war of liberation had cost more than one million lives.

It was impossible to copy Mao’s strategy of “people’s warfare” in the Palestinian context. Lacking vast forests or remote mountain regions, the “tight geography” made it impossible to establish secure base areas within Palestine. Nor could the neighboring weak states provide a secure base for the resistance movement. In addition, Vietnam had the full material and political support of both China and the Soviet Union, and the Vietnamese had a long fighting experience from the struggle against France.

The geography of Palestine and the surrounding countries was not well suited for people’s war. The Palestinian resistance forces were always within reach of Israel’s superior military technology.

The problem of a lack of a secure base area, in combination with an overestimation of one’s own strength, became clear in Jordan in September 1970. In the late ’60s, the Palestinian liberation organizations in Jordan operated very openly. The Fedayeen carried their weapons openly in refugee camps and on the streets of Amman. Jordan was used as a base of operations against the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. When the PFLP used an old British airfield in Jordan to land two hijacked airplanes, transferring the passengers to the Intercontinental Hotel in Amman and then blowing up the planes – all without any interference from the Jordanian authorities – it became obvious that the Palestinian resistance constituted a dual state power in Jordan. Palestinians comprised 60 percent of Jordan’s population and King Hussein perceived them as a threat to his rule. In September 1970, he ordered a full military attack on the refugee camps, to drive out the resistance movement. After heavy fighting – known as “Black September” – in which as many as 20,000 Palestinians died, the Palestinian organizations were forced to leave the country and relocate to Lebanon.

After their expulsion from Jordan, a discussion emerged within the PFLP between Secretary-General George Habash and his old comrade Wadi Haddad[15], head of the so-called “external operations” section of the PFLP. The guerrilla strategy that had been proposed in Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine was proving difficult to implement, as Black September confirmed. Instead of forests or remote mountains, the Palestinians were using the refugee camps in a weak state neighboring Israel as their rear base. Yes, they were like “fish in the water” in the camps, but the camps were easy targets for enemy attacks. Attacks that cost civilian lives. A humanitarian problem and a problem for the future support of the revolution.

Wadi Haddad argued that the lesson to be learned from Black September was that the “openly armed presence” of the resistance movement made them an easy target for the enemy. Had the Jordanian army failed to drive out the Palestinian organizations, the Israeli Army would have finished the job.

According to Haddad, the resistance should go underground until it reached sufficient strength to confront the enemy directly. George Habash acknowledged the problem but insisted that the resistance movement had to stay aboveground to remain in close contact with the mass movements. Besides, one needed to defend the refugee camps in Lebanon, especially given the right-wing forces operating in the country in the developing civil war.

The two lines existed parallel to one another for several years, with neither able to claim success. Haddad’s “PFLP-External Operations” became a small elite organization based in Iraq. It did not implement the underground tactic within occupied Palestine, but pursued the line of “international operations”. When Wadi Haddad had organized hijackings and similar high-profile actions as a PFLP member in the late sixties, the goal had been to put the Palestinian question on the world map. In this, he succeeded. A prime example is the aforementioned landing of two airplanes in the Jordanian desert.

However, Haddad’s operations became increasingly brutal and unsuccessful, both practically and politically. For example, the attack on passengers at Lod airport near Tel Aviv in May 1972, and the hijacking which ended at Entebbe airport in July 1976. The spectacular international operations were intended to make world opinion aware of Israeli atrocities, the Arab reactionary states (OPEC), and imperialism in general. Members of other organizations often participated in its operations: the Red Army Faction, the Japanese Red Army, and individuals such as Ilich Ramírez Sánchez. However, these operations did not have a positive international effect and did not have a mobilizing effect on the Palestinian people.

Furthermore, Haddad’s operations often involved contacts with state intelligence services: Iraqi, Lebanese, Syrian, Libyan – even the DDR STASI. For revolutionary movements, such contacts can be dangerous, as intelligence services might betray you. They have their own agenda, and it is often very different from yours. Haddad died in 1978 probably poisoned by Mossad and the PFLP-EO subsequently dissolved.

As for the PFLP, when it moved to Lebanon in 1970 it maintained an open military presence in contact with the masses in the refugee camps. This strategy allowed them to be a revolutionary force in Lebanon, working together with local communist and socialist forces in the civil war against Falangist forces. At the height of their strength, at the end of the ’70s, the PFLP and Lebanese progressive forces controlled the southern part of Lebanon, the Beqaa Valley, and the southeastern part of Beirut. The PFLP was a well-established organization. It had an armed wing with training camps and a military academy and party school; it ran clinics and children’s homes, and even had a pension system for families of fallen or injured Fedayeen.

However, the story of Black September in Jordan repeated itself in Lebanon. Israel could not tolerate the existence of a revolutionary Palestinian semi-state power at its border. As the Lebanese right wing was not able to crush the united front of left-wing Lebanese forces and Palestinian resistance movements, the Israelis had to do the job themselves. With no secure base, the Palestinian military and political organization was easy prey for the superior Israeli army, which invaded Lebanon in 1982 and laid siege to Beirut, resulting in massacres in the refugee camps and the forced expulsion of the Palestinian organizations to different Arab countries. The PFLP chose to relocate to Syria, so as to at least be in a country bordering Palestine. However, the PFLP’s position in Syria was quite different from its position in Lebanon. In Syria, the group could not be an internal revolutionary power; it was under the thumb of Assad’s Ba’ath regime.

The PFLP continued to insist on an aboveground presence, even in Palestine. In September 1999, as Habash’s health was deteriorating, Abu Ali Mustafa, the de facto leader of the PFLP, was allowed to return to the West Bank under a deal struck between Yasser Arafat and Israel’s prime minister, Ehud Barak. A very dangerous gambit, if the idea was that he should continue to lead the struggle. On 27 August 2001, Abu Ali Mustafa was killed as Israeli Apache helicopters fired rockets through the windows of his office. In an interview conducted shortly before his death, Mustafa had said:

“We all are targeted as soon as we begin to be mobilized. We do our best to avoid their guns, but we are living under the brutal Zionist occupation of our lands, and its army is only a few meters away from us. Of course we must be cautious, but we have work to do, and nothing will stop us.”[16]

Ahmad Sa’adat was elected Secretary-General of the PFLP to succeed Abu Ali Mustafa. He was accused by Israel of organizing the assassination of the Israeli minister of tourism, Rehavam Ze’evi, and took refuge in the headquarters of Yasser Arafat. As part of an agreement with Israel, Sa’adat was prosecuted by the Palestinian National Authority and imprisoned in Jericho prison in 2002. On 14 March 2006, Israeli forces broke into the prison and abducted Sa’adat and five other prisoners. On 25 December 2006, Sa’adat received a 30-year prison sentence from an Israeli military court. The insistence on an “aboveground” leadership in the West Bank had made it easy for Israel to cut off the head of the PFLP.

This aboveground military and organizational strategy cost the PFLP dearly. Perhaps Wadi Haddad had been right – not in pursuing “international operations”, but in that the PFLP’s military structure and leadership needed to be underground. Keeping the military organization underground is a proven strategy; for example, it was used by communist organizations in Nazi-occupied Europe during the Second World War, by the Algerian liberation movement in the ’60s, and by liberation movements in Latin America operating in an urban context.

The political strategy

The expulsion from Lebanon in 1982 also marked the beginning of an erosion of political strategy. The PFLP chose to go to Syria. However, their political role was limited under the Ba’ath regime of Hafez al-Assad, which was sliding from progressive nationalism towards neoliberal economics and more authoritarian rule. I remember from my trips to Damascus in the ’80s, how Palestinian comrades would lower their voices and look over their shoulder whenever we discussed Syrian politics. They could not play the revolutionary role inside their new host country like they had done in Jordan and Lebanon.

From 1982, the PFLP leadership was stationed in Damascus, away from the struggle inside Palestine, which from time to time flared up in Intifadas. The Intifadas were more or less spontaneous uprisings by the masses in response to the occupation. In fact, they often came as a surprise to the PFLP. The Intifadas were not part of any strategic planning by any organization. Without a strong organizational presence and a clear strategy, the Palestinian Left has been unable to lead these uprisings forward to any kind of success or to transform them into a new level of struggle. As a result, the uprisings were worn out over time, leaving the masses frustrated and in search of alternative leadership.

One option was Hamas, which combined social and health programs with rocket attacks on Israeli settlements from the Gaza Strip. The primitive rockets had a limited impact but were nevertheless met with brutal retaliatory force, which inflicted heavy civilian casualties and destruction in Gaza. Hamas’s military strategy – if they had one – did not seem to be succeeding in leading the struggle forward.

The other option, the PA, was literally born out of the Oslo Accords with the Israelis and turned out to be a kind of Palestinian self-management of the Israeli occupation.

The Decline of Socialism

However, this was not the only reason for the decline of the socialist perspective in the Palestinian resistance movement. The global neoliberal offensive was gaining in strength throughout the ’80s, putting liberation movements, progressive Third World states, and “real existing socialism” on the defensive, in economic, military, and political terms. In 1989, the Berlin Wall collapsed, and in 1990, the Soviet Union was dissolved by its own political elite. Even Communist Party leaders no longer believed in their project, so why should anybody else? We knew that the PFLP’s close ties to the Soviet Union were problematic for several reasons, but we also understood that the PFLP’s options were limited in the ’80s. They received concrete political and material support and a different kind of professional and political education from the Soviet Union and other East European countries. Especially in the 1982-83 period, when Yuri Andropov was general-secretary of the CPSU, the PFLP received support. The Soviet Union was the only power that, to some extent, could counterbalance the Israeli-US alliance in the region, providing the Palestinians with some room to maneuver. After the Soviet Union’s collapse, the geopolitical balance of power in the Middle East changed. Not only was the previous political and material support gone, but also the idea of “actually existing socialism” as a model for how a future state could be organized. The existence of a realistic and achievable alternative is important in the daily struggle. It is difficult to mobilize people for some vague socialist utopia. If a Palestinian state were to have been established at the time, it would have depended on the socialist bloc for material support and its security. The currently imprisoned leader of the PFLP, Ahmad Sa’adat, has summarized the lessons of the relationship between the PFLP and the Soviet Union in this way:

“The communist forces in the Arab world have applied the viewpoints of the Soviet Union by the book and have never developed their own theoretical and political ‘flavor’”.[17]

In other words, the Left should have developed its own realistic model of socialism, tailored to the specific economic, social, and cultural conditions in the Arab world.

The PFLP suffered from the general crisis of socialism in the ’90s. Its Moscow-orientated Marxism-Leninism seemed outdated, and it lost its former influence. The organization became to some extent economically dependent on affiliation with PLO institutions and international NGOs, which has tended to influence its political stand. The PFLP became less and less the radical uncompromising socialist alternative to Hamas and conservative and liberal nationalism in the form of Fatah and the PNA. National unity became the priority at the expense of the idea of socialism, a secular state, or concerns about the role of women.

Global neoliberalism and the dissolution of the Soviet Union made the US a hegemonic power in the ’90s. The US and NATO turned the Middle East into a war zone to seize control of the oil resources and secure its geostrategic position. The US also wanted to finish off the remnants of any nationalist Arab attempt to confront imperialism, by splitting Iraq, Libya, and Syria into small rival factional polities.

Criminalization of the PFLP

Another expression of US hegemony has been its “war against terrorism”. Under this banner, the PFLP was criminalized. Not only the organization itself, but also any support for the organization is to be considered a crime. It became illegal for solidarity organizations around the world to support the PFLP or organizations considered to be affiliated to it, either politically or materially.

The PFLP had already been designated a “terrorist organization” by the US as already as October 1997. The assassination of the Israeli minister of tourism, Rehavam Ze’evi, was the specific pretext for it being added to the list of terrorist organizations maintained by the US and EU. The killing was the PFLP’s response to the assassination of Abu Ali Mustafa. Ze’evi had been involved in the decision to kill Abu Ali and was the leader of the National Union, an alliance of ultra-right nationalist parties, which, after the terror attacks on the US on 11 September 2001, had advocated ethnic cleansing by demanding that all Palestinians should be forced out of Israel and the occupied territories.

Abu Ali Mustafa had been killed even though the offices of Palestinian leaders in Ramallah were supposed to be protected by the Oslo Accords, which Israel co-drafted and signed together with Arafat. According to the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem, Israel has killed 232 Palestinians in the 2000-8 period in so-called “targeted killings”; that is, assassinations executed by the state with no legal foundation. These assassinations have also caused the deaths of 154 civilians. This has been met with international indifference.

When the PFLP uses violence against the occupying state power, this is condemned and called terrorism. When the same state uses violence against the people living under its occupation, this is called retaliation and self-defense. The organizations that end up on lists of “terrorist organizations” are those of the people living under occupation.

After the liquidation of Abu Ali Mustafa, the abduction and imprisonment of Ahmad Sa’adat, and the criminalization of the organization, the PFLP leadership had to move back to Damascus. The ongoing civil war in Syria did not make things any easier for the PFLP, either politically or in terms of practical matters.

Organization building

The 1969 program is very attentive to the problems of the building of a Marxist-Leninist party. This is not surprising as the PFLP was in the process of changing its structure from a popular front to a party. Organization building and maintenance are still of immense importance. In the last decade, the crisis of neoliberalism has resulted in spontaneous rebellions against deteriorating living conditions, high fuel prices, unemployment, corruption, and lack of democracy. The rebellions spread around the world: Thailand, Indonesia, Egypt, South Africa, Iraq, Lebanon, Iran, Argentina, Chile – and the list goes on. These uprisings differed in many ways as to their specific context and immediate demands; what they all had in common, however, goes beyond a lack of a clear vision or strategy to reach it – they also lacked any organization capable of moving from demonstrations in the streets and squares to the kind of struggles and alliances that can lead to radical social change.

Such protest movements, despite the radical forms they take, often operate with a short-term perspective. They demand work, cheaper gasoline, a new government, another president, and political reforms. They represent the economic and political crisis of neoliberalism and the desperation of the people. It is not without danger that people participate in these revolts. They disrupt society and are uncomfortable for the system. Yet, without a clear anti-capitalist strategy, developed organization, and a diversity of forms of struggle, the powers that be can just wait for people to get tired or else can introduce some reforms and then continue to rule. These are the lessons of the Arab Spring of 2011.

Loose informal networks, mobilized and organized on smartphones via Facebook, Twitter, and SMS, are not enough. They are useful tools but an organization should be able to coordinate different forms of struggles from different sectors of society: armed struggle, civil disobedience, demonstrations, boycotts, political struggles, labor struggles, women, youth, and so on. A proper organization can develop strategies and plan for the medium and long term. It can evaluate and learn from experience in a conscious and structured way. No revolution has succeeded without a revolutionary party.

It is stated in the 1969 program that the party must be:

“an organization for the masses, emanating from them, living in their midst, fighting for their causes, relying on them and realizing its aims through and with them and in their interest.” (p. 125)

The revolutionary party is a school where its members learn to develop politics and practice it. Party members must be examples of conscientiousness, activity, sacrifice, and discipline. Without these qualities, the party loses its role as a revolutionary organization. In the past decade, it has been difficult for the PFLP to meet the task of organizing the struggle successfully.

Part 2

The Global perspective

On the method of analysis

The first part of this paper has been an evaluation and critique of Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine and its impact on the liberation struggle in Palestine. The question the second part focuses on is: How should we analyze the current situation, to develop a strategy that points towards specific practices? To answer this question, we need to go through the sequence of analysis/developing strategy/implementing strategy through various practices.

The PFLP adopted Marxism as its basis in 1969:

“Marxism [is] the science which enables man to understand the progress of societies and history and to direct and influence them.” (p. 111) “The correctness of any theoretical analysis is contingent upon its success on the field of practical application.” (p. 114)

The method is historical and dialectic materialism; however, I want to be a bit more specific on the method of analyzing the current stage of capitalism. First, I want to emphasize the use of the global perspective, which means understanding the world-system as one unified process. Capitalism was born in a long process from 1500-1900, by colonialism giving rise to the development of industrial capitalism in Europe. At the same time as colonialism connected the world, it also divided it into rich and poor countries – placing Palestine in the periphery. The integration of the world-system has been intensified by imperialism. Not only is there a global market for capital and commodities, but the production process itself has also been globalized through chains of production that stretch around the globe.

Adopting a global perspective for analysis might seem obvious, but it is not. Most political strategies take the local perspective as the starting point and then add the international perspective as a topping.

Secondly, as the development of global capitalism is all one process, then this process must have a principal contradiction. The principal contradiction determines the outcome of local contradictions, while at the same time being modified by them. Through this interaction, the principal contradiction changes over time.

The principal contradiction does not arise out of thin air. It emerges from contradictions in the capitalist mode of production, at its different historical stages. As the different classes react to these contradictions and try to give them a form that furthers their interests, the principal contradiction is expressed in political struggles.

The principal contradiction is not only an analytical concept; it is also a tool for developing strategy and practice. It is important to identify the principal contradiction as it has a huge impact on the Palestinian struggle. To identify the principal contradiction at a certain point in history, we must consider more than the general, abstract contradictions of “capital vs. labor,” “imperialism vs. anti-imperialism,” and so forth. Principal contradictions can be seen, felt, and traced very concretely. They are tangible in economic developments and political conditions. Actors can be identified in the form of governments, parties, corporations, and social movements.

This focus on the concrete and specific is important in terms of developing strategies. We cannot copy analyses and strategies from one time and place and simply apply them mechanically to other situations. We can learn from them, but the lessons have to be tailored to our local conditions.

Mao’s strategic focus on the peasantry in the 1930s challenged Leninism’s focus on the working class as the vanguard of revolutions. Mao demonstrated that “Leninism” was not a universal concept. Different movements have since tried to apply “Maoism” as a universal concept, but this is not a realistic approach either. The specific analysis of the specific situation is the living soul of Marxism. We must analyze the specific expressions of contradictions whenever and wherever we wish to be active. This is the only way to develop a worthwhile strategy. We cannot intervene on general concepts. If we know the specific character of the different aspects, then it is possible to intervene, to change the balance in contradictions, to move developments in our favor.

The Principal contradiction

The Inter-imperialist wars

Since the development of the world-system is a determining factor in peoples’ destinies, let us try to identify the principal contradiction during the past century and its interaction with regional and local contradictions in the Middle East.

The Second World War was the second round in the inter-imperialist showdown to decide who was to succeed Britain as the leading imperialist power. As we know, Germany, Italy, and Japan lost the war. The empires of Britain and France were weakened. The USA consolidated its position as the leading imperialist power. The Soviet Union, however, also came out on the winning side. The military power it had managed to amass in the 30s proved itself in its ability to overcome the German war machine.

In the transition from European colonialism to neocolonialism, which occurred under the leadership of the USA, it was possible for anti-colonial struggles with an anti-imperialist nationalist or even socialist perspective to gain strength. The Chinese revolution was victorious and proclaimed the People’s Republic in 1949. The People’s Republic of North Korea was established in 1948 and defended in a subsequent brutal war. The communist liberation movement in Vietnam defeated France in 1954. There were similar trends in the Middle East. The Iranian government under the socialist Mosaddegh nationalized its oil industry in 1951. The 1952 coup in Egypt by the Free Officers Movement, led by Nasser, took control of the Suez Canal in 1956. A revolution in 1958 in Iraq, led by Abd al-Karim Qasim, nationalized the oil industry. The Algerian war of liberation was victorious in 1962. On the Palestinian level, the ANM – the predecessor to the PFLP – was founded in 1955.

In the transition from colonialism to neo-colonialism, it was imperative for the US that the decolonization process lead to the establishment of national states open to US capital and trade. Therefore, in some instances (i.e., India) the US supported decolonization, while in situations where the anti-colonialist movement was led by socialist or communist forces, it opposed it.

The American World Order

In the years that followed World War II the USA was the dominant aspect in three important contradictions:

- The USA vs. the old colonial powers (England, France, Germany, Japan)

- The USA vs. the socialist bloc (Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China)

- The USA vs. the Third World

Let us take a look at these contradictions.

USA vs. the old colonial powers

With the USA’s hegemonic role in the world economy, European colonialism was replaced by neocolonial economics of transnational investments and a liberal world market, which expanded the significance of the unequal exchange between low-wage and high-wage countries.

Many international treaties were signed and related economic, political, and military institutions were founded. Their purpose was to administer the new neocolonial world order. The international finance and banking system was reorganized under the Bretton Woods Agreement, which made the US dollar the “world currency” and solidified the USA’s leading global position. The USA also established a global network of roughly 800 navy and air force bases in 177 countries. These allowed the US government to intervene militarily almost anywhere in the world at the drop of a hat. At the end of World War II, the USA had demonstrated the power of its nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After the war, the USA led the world’s most powerful military alliance, NATO.

In short, from the ’50s to the ’70s, the USA was the unquestioned leader of an increasingly globalized capitalism. Western Europe, Canada, Australia/New Zealand, and Japan acted as junior partners, subject to US interests.

The USA vs. the socialist bloc