Preface: the following article began as an informal report to my supervisor explaining different theories of trade imperialism that were to be mentioned in a dissertation on the history of New Zealand trading relationships. I decided to clean up that report into this article after a friend noted that it may be helpful to readers who are unsure about the distinctions between several quite different theories going by the same name: unequal exchange.[1]

The following is a critical review of the different interpretations of unequal exchange including:

- Unequal exchange due to differences in OCC.

- Unequal exchange due to monopoly rents.

- Unequal exchange due to differences in productivity.

- Heterodox theories, value transfer, and superexploitation.

- Unequal exchange due to differences in wages.

Unequal exchange caused by differences in Organic Compositions of Capital (OCC).

Unequal exchange, in its original “narrow” meaning, refers to exchanges in the context of a distortion of prices by wage disparities. Some authors instead use unequal exchange in reference to exchanges in the context of any distortion of prices. Other authors use it in a very “broad” sense to mean any exchange wherein prices are different to values, sometimes called nonequivalent exchange.[2]

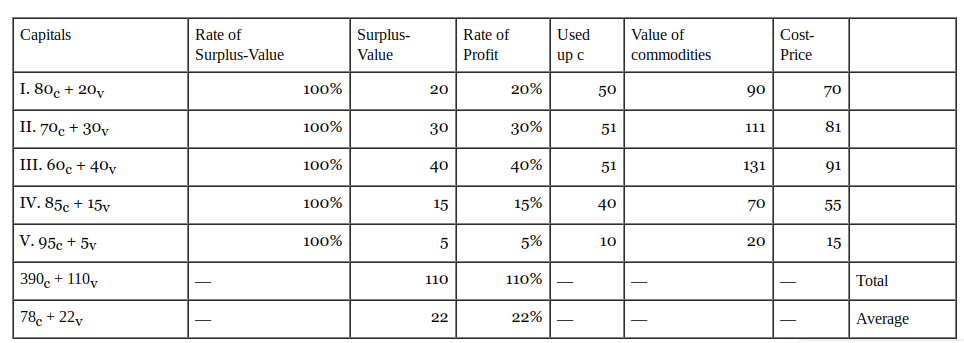

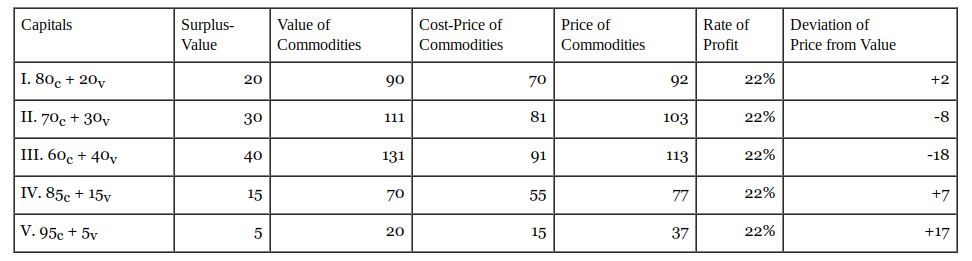

This is the view of unequal exchange advocated by Michael Roberts, Guglielmo Carchedi, Murray Smith and various other orthodox Marxian economists, based on an interpretation of Marx popularised by Henryk Grossman. They argue that the predominant form of unequal exchange is that described by Marx in part II of Capital vol. III. That is the preponderance of different individual rates of profit in different branches of production that, in the process of being equalised, shift prices away from values in such a way that the most competitive branches benefit at the expense of less competitive branches (indeed according to these authors there is a transfer of value between them). This is best explained in reference to the tables used by various authors to explain the formation of “prices of production” (prices around which market values fluctuate, equivalent to total cost-price plus profit), and since I’m too lazy to type out my own tables, let’s take some from Marx:

Here we see that unequal rates of profit have formed between different branches of production with different organic compositions of capital (c/v ratios). If the capitalist didn’t have to take account of competitive pressures and was only concerned with realising the maximum amount of value, then each branch would sell at their commodity value (c+v+s). But these branches are in fact in competition with one another, and as a result the entire sector will arrive at prices that strike a balance between maximising profits while undercutting competitors. After some jockeying and shifts in investment patterns, each branch arrives at a rate of profit equivalent to total surplus value divided by total capital invested (22%, in our example). So long as total capital investments are the same, the final prices realised will be the result of a completely even apportionment of the total surplus value produced in this sector, with each capitalist receiving 22 money-units:[3]

Here is the same sector after an average ROP has formed. Some branches have benefited from competition while others have not. The most capital-intensive have achieved prices higher than the value of their commodities. That is, they started out with a lower individual rate of profit due to the lower labour content of their goods, but through competition they have benefited from the higher sectoral rate. By contrast, all of the uncompetitive capitals had to lower their prices below their commodity values in order to maintain their profit rate. This doesn’t mean that these uncompetitive capitals are going to bankrupt themselves, on the contrary, they still have exactly the same profits as their competitors relative to their capital advanced. What makes them uncompetitive is not a difference in profitability, so much as a reduced market share resulting from their higher prices.[4]

Regardless of whether we agree that capital III is “transferring value” to capital V, there is a clear winner and loser in this arrangement, when we compare real profits to those of a hypothetical scenario without competition. Capital V is the biggest “winner” and will go on to have the largest market share while this situation holds.[5]

But it will not hold indefinitely. Over time competitive pressures will force the uncompetitive branches like capital III to raise their rate of exploitation, or invest in more cost-saving machinery where possible. They may be aided in this endeavor by investors able to see the potential increase in market share that would result. So there’s an overall tendency for more uncompetitive capitals to accumulate investments in productive machinery to offset their wage costs, although there are plenty of countervailing factors (greenfield investment costs, a smaller initial mass of profit, etc.). This is allowed by the mobility of capital – it will leave uncompetitive branches for competitive ones (if the competitive branches’ market is not already saturated, that is), or else it will make uncompetitive branches competitive over time. Capitalists are also generally aware of sectoral norms and will take steps to bring their enterprise in line. So in addition to the short-term transformation of unequal individual rates of profit into equalised sectoral rates through competition, there’s also a long-term, secular tendency towards the equalisation of those individual, pre-competitive rates of profit, derived from organic composition.

When we are talking about the equalisation of rates of profit going forward, I’m referring to the short term phenomena. The longer term trend has taken place over a matter of decades or even centuries, whereas the shorter term trend occurs wherever capital’s movement is not restricted, and branches are in competition with one another. Recent rate of profit data suggests that the average, country-wide ROP in peripheral countries has taken a very long time to match the same rates in core countries.[6] On the other hand, the rate of profit for specific goods in competition with one another suggests a much smaller difference in ROP. It stands to reason that both are in fact true: average, country-wide ROP takes a longer time to equalise because not every sector is engaged in international competition at any given time. Only those branches engaged in highly competitive, international free trade will find their individual rates of profit evening out to a global average. Another complicating factor is the almost certain possibility that there are a significant number of peripheral sectors (perhaps in the most specialised or competitive sectors) where the local rate of profit is lower than the global average.

If that is the case, then there’s not much reason to follow authors like Roberts, Carchedi, and Smith in ascribing all of the effects of unequal exchange (structural iniquities in trade between rich and poor nations) to unequal OCC. There are clearly some cases where this kind of nonequivalence might take place with dramatic effects, such as when previously protected uncompetitive branches of production are opened up to free trade, but on a global scale this is less of a unidirectional exploitative factor than a relatively mundane, persistent and omnidirectional force governing capital mobility.[7] Unless additional factors are incorporated into our analysis, the overall tendency of this kind of nonequivalence would be towards the erosion of differences in development, making for a very benign theory of global trade.

It’s also worth noting that this is the only form of unequal exchange that is inherent to free, competitive, factor-mobile capitalism, without any extra-economic influences or distorting factors. In a sense it’s not really a separate phenomenon, it’s just capitalism working in accordance with its natural laws of motion in order to form prices of production, that is to say prices that are more equal than they otherwise would be. As such I agree with those authors who describe this exchange as “nonequivalent” rather than “unequal”, instead reserving that term for cases where the prices of production are themselves distorted in some way.

Unequal exchange due to monopoly rents

This was a school of thought I initially approached with some suspicion, since I’m wary of a certain tendency for Marxists to say of any severe problem “a monopoly did it.” This is how Emmanuel treats this school (see his dismissive account in section 2.2 of “Unequal Exchange Revisited”). But I have also been swayed by arguments that there’s more to this line of thought than just “a monopoly made it so.”

Barry Finger argues that the means by which monopolies set prices is a bit more complicated than that they simply take hold of a resource and force everyone to accept their prices via state collusion and price fixing.[8] Instead, after taking hold of a sector, monopolies create artificial scarcity by letting quantities of surplus labour go unrealised as value. This might take the form of limited releases, dumping, planned obsolescence and more. By doing so the monopolised sector effectively creates a second set of prices of production, above the standard price.

From here, in addition to the monopoly gaining a greater mass of profit via higher prices, it’s also free to profit from exploiting the unequal exchange between monopoly prices and standard prices. The non-monopoly sectors are forced to accept higher prices for monopolised goods, which are exchanged for comparatively cheap elements of constant capital. This analysis also underlines how monopolies benefit from thoroughly inefficient practices, over and above the normal inefficiencies of the anarchy of production. The monopoly limits the degree to which the capitalist system expands by appropriating part of the surplus product and then underutilising it.

While I’m not convinced that monopolies account for all or even many of the effects of unequal exchange, I can see no reason why they aren’t an additional factor distorting prices.

Unequal exchange caused by differences in productivity.

There have been multiple attempts to explain the effects of unequal exchange through reference to supposed “productivity” differentials between working classes. One version of this explanation comes from the East German Economist Gunther Kohlmey, later taken up by Ernst Mandel. Workers in developed countries are simply more productive of use values (this is true enough of some industries but not others), and the value of commodities produced is inversely related to labour productivity. The world is thus split into less productive nations with a high level of value, and more productive nations with a low level of value. When goods are traded, they exchange somewhere in-between the two values, at an international rate. When the more productive country trades its goods, it gains in value the difference between its national value and the international rate. The less productive country loses in value the difference between its national value and the international rate. There’s little more to this theory than a childishly simplified version of the “UE is all about differences in OCC” theory, so I’ll move on.

Another version of this account is that given by such authors as Michael Kidron and Charles Bettelheim. Their argument is that the average worker in the core is vastly more “exploited” than those in the periphery, not in the technical sense of the word but rather in the sense that the gross money-value of the commodities produced by core workers is higher due to an enormous variable capital cost. Unlike the typical argument about OCC differentials, their argument is that core production actually has an extremely low organic composition, and the amount of variable capital invested is extremely high compared to constant capital consumed. Bettelheim’s example of a core capital is 100c, 1440v, 200s, while peripheral production is 900c, 260v, 200s. The output per worker in money-value is $17.4 and $0.5 respectively. Interestingly the actual rates of exploitation (assuming all surplus labour is realised) in this example suggest the opposite to Bettelheim’s conclusion: the rate of surplus value for core workers would be 13.8%, and for peripheral workers, 76.9%. This accidentally reveals an interesting point: under many conditions there’s a negative correlation between degree of exploitation and value produced per worker. On the other hand, Bettelheim is correct that there’s usually some positive relationship between variable capital cost and total value realised, something that, as we will see, other authors struggle with.

Kidron and Bettelheim should be recognised for at least attempting to reckon with the enormous differences in wages common in the global economy, even if their account is not particularly believable due to unsupportable claims about constant capital cost. But this whole line of thinking is still caught up in questions of who transfers value to whom, questions that I think are misstated. Even if Bettelheim’s example – which seems ludicrously exaggerated and divorced from reality to me – were true, he didn’t demonstrate that the core transfers value to the periphery.

Heterodox value transfer and superexploitation theories

“Value transfer” and superexploitation theories of unequal exchange are most commonly advocated by the recent “heterodox” school including John Smith, Zak Cope, Jason Hickel, and (to an extent) the late Donald Clelland.[9] I have referred to this school as heterodox or eclectic because it tends to mix aspects of the monopoly school with aspects of Emmanuel, Marx, Ricardo and others, in a somewhat freeform manner.

A typical heterodox argument goes like this: first we assume that the quantity of labour performed around the world is relatively equal (concrete? abstract? often it’s unclear), and so is the contribution of labour power to value realised. But because of the unequal development of political struggle, wages have become utterly detached from the real amounts of labour being performed: peripheral workers can be paid $1 to create the same quantity of value as a core worker paid $25 (unions were simply more successful among working classes that didn’t have to contend with colonial repression, imperialist wars, or racial violence). As such the labour-values imputed into a traded commodity bear little relation to the variable capital cost. The contribution of peripheral workers to the global economy in labour hours is very high compared to their wage cost, while the wages gained by core workers are actually greater than the money-value of the labour hours contributed. The different wage costs have an effect on pricing due to unequal exchange, with the higher wage cost leading to higher prices of production in core countries, and lower wage costs to lower prices of production in the periphery (this is the main aspect these heterodox theories share with Emmanuel). When the commodities produced by these two very different working classes are exchanged (their values piggybacking on them as they cross oceans), the set of goods produced in the high-waged country has a price much higher than the money-value of its labour content, while the set of goods produced in the low-waged country has a price much lower than the money-value of its labour content. And so there’s an enormous transfer of labour hours from low to high-waged countries at bargain prices. This can then be quantified in various ways, usually by measuring against a counterfactual world of equal exchange, and so we arrive at a final figure for “values transferred” somewhere in the trillions per year.[10]

Note also that the above account has certain implications for the rate of exploitation (which normally refers to the ratio of surplus labour contributed to variable capital advanced, but in these heterodox accounts seems to be treated as identical to the rate of surplus value, the ratio of surplus value realised to variable capital advanced). If core workers are contributing very few labour hours relative to their wage, then their rate of exploitation is very low, or even (Cope’s words) “a negative rate of exploitation”. Conversely peripheral workers are contributing many labour hours relative to their wage, meaning their rate of exploitation is very high, and their wages are lower than some (independently determined) reproduction cost. Thus we can employ the term “superexploitation” to describe their situation. And so the world is divided in a new way, between the underexploited and superexploited working class. John Smith’s work in particular emphasises this aspect of superexploitation.

Barry Finger and Michael Roberts have argued against the value transfer and superexploitation interpretations of unequal exchange, and I agree with parts of their assessment. However these criticisms clearly don’t disprove all wage-based theories of unequal exchange, as I will show.

The common criticism of value transfer and superexploitation theories runs like this:

- Many of these writers don’t seem to understand the process by which concrete labour is reduced into abstract labour hours, meaning they fail to understand how physiologically equal (or dimensionally incomparable) forms of labour can lead to different masses of surplus labour through a social process of mobility and competition.

- They furthermore treat capitalists as individuals who seek to realise the maximum amount of surplus labour, rather than individuals who wish to meet a price of production while minimising cost. In real life considerable amounts of surplus labour goes unrealised, sitting in warehouses as excess inventory or dumped, in order to meet price objectives.

- Since they see the value and price of labour power as diverging from one another wildly, they can make correspondingly wild claims about the rate of exploitation. According to Finger and Roberts, there aren’t many global patterns that can be unproblematically determined about ROE. Furthermore if the entire periphery were uniformly subjected to superexploitation (wages below reproduction cost) then we wouldn’t only see a stagnation of living standards but instead a total reversal, combined with constant mass starvation, and eventually a total failure of peripheral industry.

- Finally, even though there is an unequal exchange taking place in trade, Finger argues it doesn’t constitute a “value transfer” unless we are both substantialists and confused about what value is. Surely what is being transferred in trade is, on a material level, use values, and on an immaterial level, as yet unrealised quantities of surplus labour. The only place where “value transfer” happens in an economy is in the case of tertiary factors of production taking their rewards (indirect taxation, rents, interest etc.).

These are all supportable arguments aside from certain points about the rate of exploitation. While critics of the heterodox theorists are correct that it would be ridiculous to propose two poles containing totally unexploited and uniformly superexploited working classes, they overcorrect insofar as they deny any possibility that there are distinct global patterns in the rate of surplus value. We know that there’s an enormous global differential in variable capital cost – this is undeniable – but this doesn’t necessarily imply a differential in the rate of surplus value so long as we hold that there’s also a proportional (or greater than proportional) differential in surplus value produced. This would be the case only if changes in the wage corresponded exactly to changes in the value-adding capacity of labour power, and the cost of maintaining that capacity. But there are two good reasons to think that this is not the case: first, when looking at countries with very high and very low wages, it’s clear that wage differentials don’t correspond perfectly to differentials in skill or average education (although this clearly accounts for some of the disparity), and second, it’s clear that there are differences in the mode of consumption between countries. In chapter 6 of Capital vol. I Marx speaks of a “historical and moral element” of the value of labour power, which roughly corresponds to the need to maintain a “standard of living” appropriate to the culture and status of the worker in question. It would be pointless, not to mention moralistic, to divide wage goods into “economically necessary” and “luxury” groupings – leisure is itself reproductive in nature, and the contribution of the capitalist to this cost represents a real need to retain the worker in the face of competitive and moral pressures. But as the wage grows, such as when one national working class gains a significant victory, there enters a possibility that the wage can grow out of proportion with the cost of reproduction – this is the case in any “exogenous” wage increase, that is to say one not initiated by the capitalist in response to some need of his. The end result would be a decrease in the rate of surplus value without any of the changes to the organisation of production this would normally require. Of course it is also the case that certain countries have better labour laws that would themselves change the rate of surplus value by placing limits on the working day and intensity of production. But whatever the real reason, the end result is the possibility that some countries, and not others, can experience a general rise in wages without a corresponding rise in surplus value, and this possibility has extreme consequences explored in the next section.

What I think the heterodox theorists of unequal exchange are very effective at conveying is an emotional truth about unequal exchange. They find it morally horrific that wage increases in one place can lead to misery in another. This is the reaction of any compassionate person. But their economic arguments are then subordinated to their moral concerns, and distorted to suit them. This is why they call upon so many disparate concepts, from mutually opposed schools of thought, to construct arguments like a house of cards.

Unequal exchange due to differences in wages.

While many authors are critical of this or that aspect of unequal exchange, I don’t think any have come close to challenging the central theorem of unequal exchange in the “narrow” sense, given most clearly by Emmanuel in section 2.4 of “Unequal Exchange Revisited”:

“If the wage is exogenous (institutional, independent variable), and if a tendency exists for the formation of a general International rate of profit, then any autonomous variation in the wage-rate in one branch or in one country will entail a variation in the same direction of the respective price of production and a variation in the opposite direction of the general rate of profit.”

This is somewhat similar to what Marx tells us about overall wage increases in chapter 11 of Capital vol. III:

“if wages are raised 25%:

1) the price of production of the commodities of a capital of average social composition does not change;

2) the price of production of the commodities of a capital of lower composition rises, but not in proportion to the fall in profit;

3) the price of production of the commodities of a capital of higher composition falls, but also not in the same proportion as profit.”

The difference is that we aren’t raising the general rate of wages. In Marx’s day there was less reason to assume that the struggle over surplus value would achieve such uneven success. Wages between British and Indian workers were roughly comparable, with the exception of a small British labour aristocracy, and it was only in the post World War II period that wage disparities assumed their present day form of an enormous difference in the wages of whole national working classes.

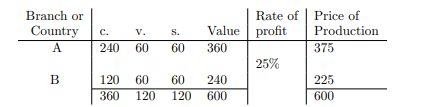

Emmanuel’s theorem instead applies to a general rise in the wage rate of one country, unmatched by another. It’s easiest to see this theory in action in the context of a Marxian prices of production table such as that I included earlier:[11]

To this example we can apply an “autonomous variation in the wage-rate” (for example a rise in unionisation in one country, unmatched in the other) in this case an increase of 33% in country A, as well as a reduction in the rate of surplus value to 50%. In such a case the composition of that country would be 240c, 80v, 40s. Country A would find its prices rising to 384, while country B’s would be 216. This is a 2.4% rise in the prices achieved by country A, while country B sees a 4.16% decrease in local prices. In both countries, the deviation of prices from values increases from 15 to 24. As a secondary effect, the average rate of profit is lowered, and while in the case of a general increase in wages this would negate any benefit to the capitalist in country A, in the case of unequal wage rises these negatives are compensated by changes in the terms of trade and other factors. To be clear, this arrangement is worse for the capitalist class as a whole in terms of absolute profit, but it is not intolerable due to the many compensatory advantages gained by the capitalists of high-waged countries.

This is only possible in a global context where labour is less mobile than capital, since the rate of wages could equalise in much the same way as the rate of profit if there was perfect global factor mobility. In my opinion these assumptions correspond well to a world of increasingly severe immigration controls, and a difference in real wages between core and peripheral countries less like 33%, and more like 1000%.[12]

Note also how an increase in variable capital without a corresponding increase in surplus value must imply a decrease in the rate of surplus value. Unequal exchange in a narrow sense is therefore necessarily an argument that the rate of surplus value, and consequently the pressure to increase the rate of exploitation, is lower in richer countries. But this doesn’t require us to argue that increases in variable capital, as well as various secondary factors associated with institutions of the working class over the last century, have not increased the average skill and efficiency of workers in high-waged countries, only that any resulting increase in surplus value contributed is not exactly proportional to the increase in wages since the postwar period.

Note that there’s nothing here about value transfer, negative exploitation, or who deserves what. The majority of the critics of unequal exchange have been so preoccupied with countering secondary claims about political consciousness and economic justice that Emmanuel’s central claim has been buried under a lot of discourse that has little to do with it. This is not to say that Emmanuel doesn’t make such secondary claims, but these aren’t the aspect of his thought I find interesting.

To accept the central theorem brings several implications for the study of historical development. While Emmanuel didn’t think that unequal exchange was necessary for development (most of the material benefit goes towards inefficient consumption), he did think that wage differentials created enormous supplementary benefits for capitalists. Constant wage growth creates expanding markets, more investment opportunities, and an overall expansion in the mass of profit in overdeveloped areas. Other economists like Hartmut Elsenhans further developed the idea of wages as a factor of development. If the assumptions of the central theorem correspond to reality, then we would expect to see cheapened elements of constant capital, more investment opportunities, a greater mass of profit, and further benefits.

Where to from here.

I hope that this short account has clarified why I think it’s necessary for Marxist economists to reconsider Emmanuel’s original theory of unequal exchange and the way it applies to the present day. It’s necessary to do this without confusing Emmanuel’s central theorem with other authors’ versions of unequal exchange, although other concepts going by the same name are clearly worthy of investigation. It’s also necessary to consider it separately to various secondary claims to which it’s frequently attached: I don’t think that to accept this theorem means we must also accept that there’s a “value transfer” in trade, uniformly different organic compositions, or notions of negative exploitation. I certainly don’t think that unequal exchange should be used to derive moral claims about who “deserves” rewards for labour – this kind of thinking belongs to pre-Marxian socialism. That being said, it’s only right to be appalled by global inequalities which have created exploitable opportunities to hoard benefits at one pole at the expense of another. A sober analysis of the contradictory determination of these inequalities is necessary for practice to begin to resolve them.

Endnotes

- I’m not immune to this confusion, as anyone who’s read any of my previous articles on the subject would agree. ↑

- That is to say, pretty much all exchanges outside of the quite unlikely case of two capitals with exactly the same organic composition and rate of turnover, see Morishima (1973, chapter 7) for discussion of this special case. ↑

- This might be called the “pigs at a trough” theory of profit – the trough is as long as the market for a commodity is large, and despite some initial jockeying to get a place at the trough (which might involve certain inequalities in effort expended by the pigs), each pig gets their share once their position is secure. ↑

- In practice efforts will be made to reduce the price difference further, but without a more fundamental change in composition this cannot be done without sacrificing profit. ↑

- Note also that these prices of production assume, quite unrealistically, that all surplus labour hours are realised. The only thing stopping Capital V from gaining additional money-units per commodity (beyond a certain point it would become less competitive than Capital IV) by not bringing its full inventory to market is the question of demand. ↑

- Maito’s study is not the most up-to-date, but it most clearly shows differences in national averages which are slowly equalising. ↑

- That is not to say that this special case doesn’t ever result in the immiseration of whole areas. An example close to home was the highly protected dairy industry in Northland that benefited from government price controls until the 1980s. Once those protections were lifted and the area was made to compete on global markets, there was an extreme case of capital flight. The transitional period would have been marked by this form of “unequal exchange” due to competitive differences, and the region has been considerably poorer in relative terms ever since. ↑

- This seems to be what Walter Rodney and some other Monthly Review-inspired authors thought, and I’m not saying this doesn’t ever happen, but without a change in the volume of goods brought to market this would still result in additional problems for the monopoly company, such as market oversaturation. ↑

- Clelland doesn’t entirely deserve to be grouped here. His theory of “dark value” transfer is clearly conceptually distinct from other “value transfer” theories and has some heuristic value not otherwise discussed in this article. Nonetheless he was influential among these authors. ↑

- Cope says $2.8 trillion per year (mostly using 2013 data), based on measurement against a counterfactual where everyone is paid the median wage. Hickel et. al., using a similar method but measuring against a counterfactual where the prices of production are everywhere equivalent to that of the core, reach the figure of $152 trillion transferred from 1960-2021. The Hickel method is a bit sillier than the Cope one, because whereas in Cope’s counterfactual it’s at least feasible that equal wage rates (imposed by some alien invasion force that also wishes the world to retain a capitalist mode of production) would result in global conditions of equal exchange, there’s no universe in which the entire world’s commodities would exchange at an inflated price of production for any reason. ↑

- This table is based on one in Emmanuel (1972, p. 55). As Emmanuel notes it is simplified and has some unrealistic assumptions about cost price (which would be lower if we separated the constant capital actually used from the totals invested), but the effects of unequal exchange are exactly the same as in more complex tables. ↑

-

More still if we exclude the rise in Chinese wages. However the “real wage”, even if it does adjust for purchasing power, also doesn’t tell the whole story, as in high-waged countries certain reproduction costs (such as housing) rise out of proportion with others. ↑