There is a world of difference between the class struggles in the “South” and “North”, although they are part of the same global system. This difference is due to imperialism, which divided the world into an exploited part and an exploiting part. The industrialization of the “South” in the past decades, with hundreds of millions of new proletarians has shifted the balance of global capitalism and created a new division of labor, wherein the “South” mainly produces and the “North” mainly consumes. The capitalist production process itself is becoming more and more globalized through the establishment of production chains controlled by companies in the “North”, transporting goods produced by the proletariat in the “South”, to the consumers in the “North”. Through these commodities, a stream of value flows from “South” to “North” hidden in the cheap prices, created by the low cost of labor in the “South”.1

While this mode of production is integrating neoliberal capitalism and imperialism into one globalized capitalism, it divides, at the same time, the global working class and thereby the form of class struggle in the “North” and the “South”. In the South, we have an exploited proletariat struggling against global capital, often in a framework of a repressive state. A classic proletarian class struggle. In the “North”, the situation is much more complex.

Class struggle in the parasite state

The relatively peaceful form of political struggle in the “North” does not mean that the state is an expression of cooperation and reconciliation and that class struggle between capital and labor is ended. The parasite state in the “North” is capitalist. However, it is a particular form of capitalist state. The system of government is parliamentary democracy with universal suffrage. The state is committed to a welfare system of some kind. There are certainly differences in the extent and form of welfare between different states in the “North”, and the welfare system has certainly come under pressure from neoliberal policies in the last decade, but even liberal and conservative politicians are committed to the welfare of the population to some extent. Such a state formation can hardly be described as the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. But, who then has the power in the parasitic state and what is the nature of its class struggle?

The state is the organization that class society – out of struggle – creates to safeguard the conditions for its mode of production. Just as the absolutist state in the 17th century represented a sharing of power between the feudal nobility and the emergent bourgeoisie, the modern liberal parliamentary states in the “North” represent a division of power between capital and the working class.

In the modern liberal democratic system, the head of government does not represent the exclusive interest of capital nor the working class – but simply the current mode of production. The Power (usually) accrues to the government that is best prepared to maintain and develop the existing mode of production.

Marx describes in “The Class Struggles in France” how the bourgeois republic’s constitution worked in the 19th century. It is a constitution that, by the universal suffrage, gives political power to the classes whose exploitation it guarantees. The constitution thus deprives the bourgeoisie its political guarantee so that it can maintain the social power that very same constitution approves.2

“The comprehensive contradiction of this constitution, however, consists in the following: The classes whose social slavery the constitution is to perpetuate – proletariat, peasantry, petty bourgeoisie – it puts in possession of political power through universal suffrage. And from the class whose old social power it sanctions, the bourgeoisie, it withdraws the political guarantees of this power. It forces the political rule of the bourgeoisie into democratic conditions, which at every moment help the hostile classes to victory and jeopardize the very foundations of bourgeois society. From the first group it demands that they should not go forward from political to social emancipation; from the others that they should not go back from social to political restoration.”

Contemporary European constitutions function in a similar way. The law guarantees the private ownership of the means of production–and thereby the bourgeois economic domination and means for global exploitation. However, the constitution, through universal suffrage, at the same time makes it necessary for this bourgeoisie–politically–to take account of the working class in the “North”. Thus, the constitution “requires” the working class not to use its political emancipation (universal suffrage, freedom of expression and to organize.) to further the cause of economic emancipation. On the other side, the bourgeoisie must be “content” with economic power, and not also demand full political hegemony. Therefore, the political struggle is limited to which class or combination of classes, at different times, is fit to use the parasite-state’s legal regulatory apparatus to its own benefit–within the framework of the existing capitalist society, of course.3

The limitations of “Northern” class struggle

It is important to understand the nature of the class struggle in the North. It has not ceased with the establishment of the parasitic state and the labor aristocracy. The establishment of the labor aristocracy itself is a consequence of the class struggle. The working class had to fight for its economic progress and political rights – they were not merely giveaways from capital. However, the class struggle in the “North” is not capable of breaking the framework of capitalism.

The reason the working class struggle is limited to take place within the framework of capitalism is of course imperialism and the establishment of parasitic states. The imperialist division of the world into countries with high wage levels and countries with low wages solved the economic and political crisis in the mid-nineteenth century. Instead of revolution, capitalism continued to develop for 200 more years. Colonialism secured the profit rate, and the rising wage levels in the “North” created a growing market that ensured capitalism’s steady and necessary extended accumulation.

This economic dynamic and the development of parliamentarianism in the “North” simultaneous created the political framework that could handle the power struggle between capital and the working class, in a way that secured capital with a stable platform and social peace at home, on which it could develop and maintain imperialist dominance in the “South”.

The welfare state

This relatively independent capitalist state, resting on the sharing of power between the working class and the bourgeoisie, was consolidated as the working class began to manage its social problems within the framework of capitalism. The class struggle between capital and the working class in the “North” has gone back and forth. The Labor aristocracy took the lead from the late 1950s until the mid-1970s. Capital took the lead in the “golden days” of neoliberalism from mid-1970s until today. However, there has not been a fundamental difference in the policy, whether it has been liberal or social democratic parties, which have been in power in North-west Europe during the last half century. Political parties must adapt to the same basic economic policy, to ensure the orderly accumulation of capital on a world scale. The parliamentary system plays a role, concerning the form and distribution of the spoils from imperialism, but a limited role. The change is mainly the result of the global economic and political struggles outside the national parliamentary system. Parliaments reflect these changes more than they can control them. Exemplified with the Social Democratic welfare policy in the 1960s and early 70s, followed by neoliberalism in the next decades.

The capitalist welfare state developed as a new way for the state to control its population. Suppression, in the main, went into the background. Instead, it seeks to unite the people and government in a mutually reinforcing symbiosis to the nation. Only national citizens are entitled to receive benefits from the state, non-citizens are excluded. It creates a sense of common interest between the state and its national citizens, which constitutes the national interest. As individuals, we are mentally and physically surrounded and cared for by the welfare state in this national context.

This shift from working class identity into an identity as national citizens did not ease the political struggle. This national sentiment in the working class is just as much a problem for global capitalism, because it is a hindrance for the development of the transnational state structure necessary to ensure a “smooth” accumulation of capital. It is this conflict, which is reflected in the current political crises in the EU.4

One might say that big capital, in the form of neoliberalism and globalization of production, has eroded the political/institutional foundations of the worker-capital power-sharing agreement: The national parliamentary democracies’ ability to regulated capitalism in the interest of the working class.

In Europe, the working class, often represented by right wing nationalist parties, is trying to rebuild this national framework to protect itself from the negative aspect of neoliberal capital (immigration, outsourcing, erosion of welfare) while still trying to reap the benefits of global capital (cheap goods). Both capital and labor, however, must live with the compromises and contradictions that the parasite state arrangement entails.

From the late 1970s onwards, the welfare state has come under increasing pressure due to the development of neoliberalism. The relocation of production to the “South” affects class relations in the “North” in a complex way. Low wages in the “South” means cheaper goods for the workers in the “North”. The low wage in the “South” also means higher profits for capital and thereby an ability to maintain the “social contract” by retaining relatively high wages on the “home front” in the “North”. However, since the financial crisis of 2006-2009, these high rates of profit are on the decline – partly because of internal competition between capitals, which tends to equalize the rate of profit. Relocation to the “South” has becoming so common that the trick is not so effective any longer. Partly due to wage-struggles led by workers in the “South”. For instance, the average wage of industrial workers in the export sector in China was about $ 0.75 per hour in 2005, compared with $2.25 in 2011.5 Finally, it is very difficult for capital to dissolve the welfare state due to the parliamentary system. Thus, the logical result is the rise of right wing nationalism in order to defend the working class privileges in the “North”.

The Labor market in the North

Globalized production is increasingly placing the working class in the “North” and “South” in direct competition with each other. It gives capital the chance to increase the pressure on the wage level in the “North”—a development that began in the textile industry, but has spread to virtually all sectors. We are beginning to see a division of labor in the “North” with very different wage levels determined by the global division of labor, as well as legal and illegal immigration:

- Illegal immigrants: They work, for example, as strawberry pickers in Spain, tomato pickers in Italy, in the “black economy” in the cleaning sector and restaurants. They have the lowest wage level in the “North”. They work to survive and send a little money home to the family. They place pressure on the wages of organized and unskilled labor. They are outside the welfare system. They are victims of social exclusion and racism.

- Legal immigrants: They can work inside or outside organized labor. They often accept lower wages than the “national” workforce accepts, and therefore place the unskilled as well as skilled workers wage levels under pressure. They work in construction, service, health, transportation, catering, cleaning sector and other jobs that cannot easily be moved to the “South”. They too are often victims of racism.

- Unskilled and skilled workers: These workers’ wages are under pressure from the relocation of industry to the “South”, as well as competition from legal and illegal immigration. These workers comprise the entire industrial sector—textiles, machinery, electronics, automobile factories, shipbuilding, slaughterhouses and so on. The wage level in these sectors have, in recent years, been under pressure and typically stagnated or fallen. This phenomenon occurs especially in countries with weak trade unions, as for example the United States. This part of the working class is drawn towards right wing populist parties.

- Skilled Workers in niche production such as biotechnology, pharmaceutical industry, environmental and welfare technology, etc. are still seeing a growth in wages. They are the top of the labor aristocracy. However, this is in no way a secure position, as these sectors can be outsource to the “South” in the near future. This part of the working class is drawn toward “New Labor”—type trend, the neoliberal social democracy that desperately tries to combine neoliberalism with the protection of a welfare state.

- The administrative and “creative” class: They work in administration, finance, logistics, design, development, branding and marketing of products typically produced in the “South”. This group, in the “North-end” of the global production chain, has experienced wage increases in the last decade. They tend to unconditionally support continued neoliberal globalization.

In the next decades I think we will see the development of a more and more polarized labor market in the “North” between the parts of the workforce capable of placing themselves in attractive positions in the global division of labor, and that part of the working class which must compete against the proletariat in the “South”.

The latter part of the working class will not passively accept this development. Naturally, in the years to come, we will see contradictions between this part of the working class in the “North” and capital intensify. The structural crisis of capitalism will sharpen this conflict. To keep up the rate of profit, capital must put pressure on labor everywhere, “North” and “South”.

In its struggle against capital, the working class in the “North” finds itself in a complex situation: On the one hand, neoliberalism is dismantling the welfare state that the working class had built up through the 20th century. On the other hand, this neoliberalism is a precondition for globalized production, which undergirds the rate of profit, and thereby capital’s ability to pay a high wage rate for the necessary work in the “North”, and thus the taxes, which allow for the maintenance of the welfare state.

The labor aristocracy finds itself in a double position in relation to capital. At the global level, the working class in “North” thus benefits from the way global capitalism functions. But to cash this advantage, the working class must engage in class struggle against capital at the national level. The labor aristocracy wishes to preserve capitalism, but in a form that continues to ensure them a privileged position. This is becoming more and more difficult.

To handle this difficult and schizophrenic position, the labor aristocracy has largely abandoned the identity of a working class and instead adopted an identity as citizens of a privileged nation. Politically, this is reflected in a movement away from social democratic and revisionist parties towards right wing national populist parties. This does not at all end the conflict with neoliberalism — on the contrary! Right wing nationalism is as much a drag on global capital as the old social democracy. It is important to understand the complexity and contradictions that the shared power between capital and labor produces in terms of strategies of both the contending classes.

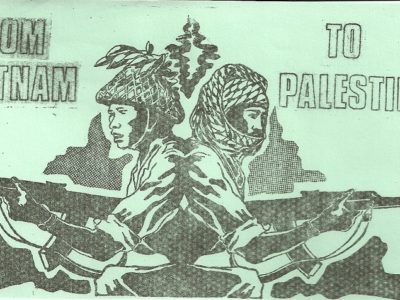

It is also important for us to explain, not only how class struggle in the “North” and “South” are different in form and content, but also how they interact. It is our job to explain when the class struggle in the “North” between capital and the working class is a division of the spoils from the “South”. But, also, when it is possible to develop political struggles in the “North” that interact with the class struggle of the “South” in a progressive manner:

Struggles concerning immigrants and refugees,

Struggles against right wing nationalism,

Struggles against military intervention

And even, when it is possible, to connect trade union struggle in “North” and “South”

We cannot just wait for the struggle in the “South” to overthrow global capital. We must not de-mobilize people in the “North”, but contribute to the common struggle with the proletariat in the South.

If our description of the labor aristocracy does not encompass this dynamic of national and global class struggle, and our description of the parasitic state does not include this element of political struggle, then our understanding of imperialism will lack any explanatory power. On the one hand we must take advantage of the contradictions that the parasite state creates, and on the other hand be realistic in relation to the limits of the class struggle in the parasite states.

Link: Class Struggle in the Parasite States

See also: Torkil Lauesen and Zak Cope: Imperialism and the Transformation of Values into Prices. Monthly Review, Volume 67, Issue 03 (July-August 2015) ↩

K. Marx: The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850, Part II. From June 1848 to June 13, 1849. ↩

For more on the nature of the parasite state, see: Zak Cope and Torkil Lauesen: introduction to “Lenin on Imperialism and Opportunism” Kersplebedeb, forthcoming. 2016 ↩

See also Torkil Lauesen: The EU Crisis. 2016 Anti-Imperialism.com ↩

Merrill Lynch, Bank of America. Quote from Reuters.com. 4.4. 2013. ↩