Below is a special report written in collaboration by The Cadre Journal, the University of Johannesburg Centre for Social Research and Practice (CSRP), and the Marikana Support Campaign in advance of the 10th anniversary of the Marikana Massacre of 34 mineworkers on South Africa’s platinum belt on August 16th, 2012. The report traces the anti-imperialist organizing resisting mining companies after the massacre and focuses on South-South solidarity from Chile as miners exploited by Anglo-American mining companies forged solidarity across a transnational divide.

Marikanamostrecentversion-compressed

Download the PDF.

Anti-Imperialism in the 21st Century: Solidarity after the Marikana Massacre in South Africa

What Really Happened at Marikana?

On 16 August 2012, 34 striking mineworkers were gunned down by police in Marikana, South Africa. The blood spilled outside the platinum mine would seep into the earth and taint the precious metals in the “open veins” of the global South; this platinum moves along the arteries of a global supply chain that empties into the global North. The platinum, the commodities produced with it, and above all the value at stake in its continued excavation sealed the fate of the miners and pulled the triggers of the automatic R5 rifles used by the police in what would become known as the “Marikana Massacre”. Seventeen were killed on strike at the “koppie” (small mountain), but another seventeen were tracked down and killed execution-style while fleeing. The workers’ “crime”, for which they were summarily executed? Refusing, even temporarily, to advance the slow bleeding of their country’s resources by the vampire, Capital.

What was the value of a mineworker’s life to the companies that used them to mine platinum? We can compare how cheaply the company purchased them, and how easily it slaughtered them. Lonmin (London Minerals) paid its miners at Marikana a pittance of R48,000 ($6000)[1] a year so that it could earn R48 million ($6 million) a day from their labour. Its CEO got a bonus 236 times that wage, to live in luxury while the workers in Marikana lived in shacks.[2] The massive value that these workers produced for Lonmin and its owners was distributed along a global value chain that affects every one of us. With 86% of world platinum resources, South Africa is of major interest to global corporations. One example is Badische Anilin-und SodaFabrik (BASF), a German chemical company that was Lonmin’s biggest customer and the biggest chemical enterprise worldwide. BASF has more than 570 business units in more than 80 countries, serving as a supplier to almost every branch of industry. BASF made annual purchases worth $660 million from Lonmin, buying 50% of the Marikana mine’s yearly production, and the mineworkers produced $2 million worth of platinum a day for BASF.[3]

Huge value was at stake during the strike in 2012, and the companies saw this as being worth far more than 34 lives. It wasn’t just the companies with interests at stake when workers refused to mine. The platinum mined at the far end of the global periphery, through BASF, ends up in a wide variety of products consumed in the global North. BASF’s chemical products are in everything from video game consoles to cosmetics, baby diapers and sneaker soles. Most essentially, they are used in vehicle catalytic convertors. Cars in the global North, among other products, are at the end of a long supply chain that stretches from the veins of Marikana. The products that can be purchased so cheaply by global North consumers are only accessible because such cheap labour is employed to dig up the resources needed for production.

This is imperialism; this is the killer still on the loose ten years on. But now is a moment to revitalize our opposition to the global forces that are culpable in this mass murder. What workers did at Marikana threatened the very structure of extraction and exploitation that props up the domination of the global South by the North. Their killing shows the violence that imperialists use to maintain domination. Within the decade that has passed, we must not just remember the slain, but must use the spirit of Marikana to construct an anti-imperialist politics that will fundamentally challenge this domination. We can all learn valuable lessons from the massacre about resistance to imperialism in the global South and the actions we can take in solidarity. Everywhere, we must learn from the anti-imperialists at Marikana, and those who sought justice all along the global value chain; they understood that justice can only be achieved when the exploitative world system of extraction is overthrown. The veins of the south remain open,[4] and the bleeding continues. Reflecting on the killings at Marikana ten years later, we hope we can envision a strategy to close the wounds and begin to heal.

Defining imperialism and anti-imperialist solidarity

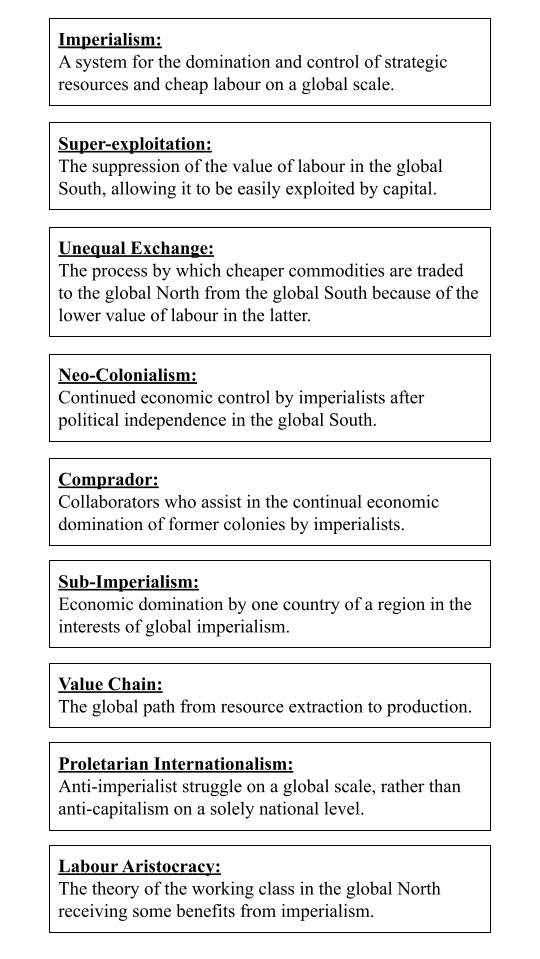

Some Key Terms:

Though much has changed in the structure of capitalism in the 21st century, the struggle of our time remains principally against imperialism. We must read the struggles of workers in a global context; likewise, solidarity for one struggle cannot be localized in one country but must take on an internationalist dimension. But to know what we are against, we must define it. Imperialism cannot just be vaguely defined; critical to modern imperialism is super-exploitation, which is defined as “the value of labour power… being forced down in some countries [the global South] but not in others”. The preservation of cheap labour in the global South is the key feature of the imperialist system today; as John Smith concludes, “imperialism and super-exploitation are … the same thing”.[5] In South Africa, the history of colonialism and the apartheid white supremacist regime, from 1948 to 1994, all operated on the exploitation of cheap African labour for white capital, both the settler-colonial and foreign imperialist varieties.[6] This relationship contributes to an unequal exchange – those in the global North can purchase products cheaply because workers’ wages in the global South are so far below their real value.[7] This system is preserved by foreign imperialist capital from institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank; in 2007, Lonmin received a $150 million investment from the World Bank’s Investment Finance Corporation (IFC).[8] Imperialism is critically preserved by neo-colonialism, where post-independence governments that are seemingly run by indigenous people, but continue to be dominated by imperialist powers, serve the function of oppressing workers and keeping wages down with state power.[9] Some further argue that South Africa is a sub-imperialist nation that imposes capital investment and super-exploitation on other African nations but does so as a regional agent of American imperialism.[10]

In the case of South Africa, for instance, after the defeat of colonialism and apartheid, and the rise to power of a majority government, imperialists still call the shots. The only difference is that they now do so with the aid of a comprador (collaborator) class: the post-apartheid government represents an ally for imperialism, engaging in a “toxic collusion”.[11] After the massacre, it came out that “the Marikana police operation had clearly been carried out in intimate coordination with Lonmin … the police shooting was carried out on the company’s behalf, with the knowledge of its executives and at their urging”[12]. Albert Jamieson, Lonmin’s chief executive, wrote to the minister of Mineral Resources, Susan Shabangu, on 13 August 2012, demanding that “the State… bring its might to bear on this crucial sector of the economy”. The comprador class found its main representative in Cyril Ramaphosa. Ramaphosa was then on the Lonmin board as a major shareholder; today, he is the president of South Africa. Ramaphosa reported to Lonmin executives that he was urging the government “to understand that we are essentially dealing with a criminal act … dastardly criminal … there needs to be concomitant action to address this situation”.[13]

More powerful than individuals, however, is the law of South Africa, structured to the benefit of imperialism when Apartheid fell. It protects imperialists’ “freedom to repatriate profits and capital” and “their rights to exploit minerals” in South Africa’s contemporary mining regulations.[14] All this allows imperialists to divert super-profits from super-exploitation out of the country. Lonmin diverted super-profits via a tax-haven loophole that served as “a source of at least $100 million in capital flight from South Africa to Bermuda”.[15] This is “the equivalent of at least R3500 [a] month extra for each rock drill operator’s wages”, stolen instead of being given to those who work. Andy Higginbottom notes that “Marikana demonstrates the continuation of super-exploitation in post-apartheid class relations”.

To triumph over imperialism, and give us any hope of a future, we must revive an anti-imperialist solidarity that provides critical support to the fights against the domination of the most exploited workers in the world. Our challenge is how to envision this solidarity using the tools we have. Nemanja Lukić has argued that anti-imperialist organizing must be transnational and anti-systemic. For Lukić, “it is of key importance to put the context of a struggle into its relation to the processes and actors in the whole world… and to have a clear position which would weaken imperialism”. In other words, the focus must be “global from the beginning, rather than being principally national”.[16] Solidarity campaigns were common ways to do this in the past, especially during the struggle for decolonization in the last century. In the 21st century, campaigns have galvanized students, workers and activists across the world to mobilize in solidarity against the American war on Iraq, the brutal blockade of Cuba and the Israeli occupation of Palestine, for example. Solidarity, in a popular definition, means providing critical support (financial, material, political) to struggles waged by others (ranging from groups of workers to entire nations) for their own sovereignty, arising out of a common political goal.

In the case of anti-imperialism, solidarity campaigns represent a global effort to defeat a system that enables the super-exploitation of workers on the periphery. If imperialism relies on control of valuable resources and easily exploitable workers, then movements that threaten this control threaten the domination of imperialism. Providing support to a struggle that targets imperialist domination provides the opportunity to attack imperialism at its weak points. Indeed, if imperialism relies on control of the globe, then breaking its stranglehold in crucial areas is one strategy towards ending its domination. The common program of anti-imperialism, defined from this perspective, is the defeat of capitalism, the advancement of socialism, and the national liberation of oppressed nations and peoples.

So, what does an anti-imperialist solidarity for the 21st century look like? There are many questions which we must consider from the outset. Later we will examine how these were interpreted in the case of post-Marikana solidarity organizations and actions.

- What is anti-imperialist praxis? Different solidarity organizations have endorsed different tactics in the past, ranging from “raising awareness” among those who were unaware of a struggle, to personally intervening in that struggle, with one example being the London Recruits, young British leftists who assisted the anti-apartheid uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) in its early days.[17] This internationalism is still a method of solidarity, but we must also study our conditions and discover how we can advance anti-imperialism in all directions: North-South, South-South, and even South-North. There are also questions of legality: some anti-imperialist groups operating in the global North, such as the Danish Blekingegade Group, have engaged in illegal activities such as robbing banks to provide funds to movements in the South.[18] While this has been a successful method of solidarity, it has encountered severe state repression. Other instances of sustained anti-imperialist action within the core include the solidarity networks which bring aid to Cuba against the American blockade, or the BDS campaign to boycott, divest from and sanction Israeli apartheid, which itself ranges in intensity from more institutionalist efforts to sabotaging Israeli arms factories by groups such as Palestine Action. These raise the debate between propagandizing and “direct action”.

- How do we structure an anti-imperialist organization? Anti-imperialist organizations tend to be structured as united fronts, with alliances among those explicitly advancing socialism and those focused on national liberation first. This dilemma plagued many of the historical solidarity campaigns and continues to be a factor for consideration; in Palestine organizing, for example, some choose to be explicit in supporting a left-wing Palestinian organization while others deem all anti-colonial organizations to be progressive.[19] Solidarity organizations should make their ideology clear, so they avoid confusion on what or whom they support. Neoliberalism has weakened traditionally structured and disciplined left-wing party structures, hollowing out “social movements” and leaving them with no clear, overarching political ideology or leadership to hold accountable. The problems that affect social movements born of hashtags (internet-born organizations that are meant to be “spontaneous”, “autonomous”, and “structureless”) such as #BlackLivesMatter or #FeesMustFall, affect social movements in the global South as well. Solidarity at an international scale has been expressed for these movements, as demonstrated by worldwide BLM protests, but not in a sustained, organized, or clearly political fashion. Attempts to create “structureless” organizations often fall prey to what Jo Freeman called the “tyranny of structurelessness”.[20] It is necessary to avoid organizational authoritarianism centred on an individual, but there is no solution without an organization, and anarchistic formations result in political ineffectiveness. Nevertheless, traditional organizations such as unions and leftist political parties without an anti-imperialist ideology can easily become collaborators in exploitation. In the case of Marikana, organizations such as the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) supported the imperialist agenda.

- How do we navigate organizing on the internet? Organizers are more able than ever to issue immediate communications that can cross borders and rally people in any corner of the world. Social media is useful for furthering organization, with Facebook groups or WhatsApp group chats serving as primary ways to communicate among activists. Zoom and Microsoft Teams have become integral to organizing conversations and seminars around the world. Livestreaming events on platforms such as Instagram allows anyone to follow a mobilization while not physically present. Messaging services such as Signal and Telegram, which are encrypted, can also protect sensitive communications. As stated before, entire demonstrations have occurred because of videos and hashtags online. Marikana occurred early in a digital age when tools such as Facebook were starting to be used for organizing. But such internet organizing is rife with problems. There are serious concerns about data rights, surveillance, and privacy. Internet tools such as Canary Mission,[21] which publishes private information about pro-Palestine activists (“doxing”), are meant to dissuade any online organizing against imperialism. Worst of all, the internet is transient. The reduced capacity to commit to a long-term cause has reflected our diminished attention span and a need for something to reach our timelines before we can mobilize around it. Some pro-Palestine organizers have lamented that Palestine must be “trending” before mass action occurs, for instance;[22] we require spectacle to activate anger and activity. Similarly, Marikana sparked outrage when it occurred, but it is unclear how sustained that outrage is a decade on, when Marikana isn’t dominating social media. The internet also positively rewards factional, divisive behaviour that triggers controversy rather than unity. Lastly, some are under the illusion that posting online is the equivalent of praxis. This delusion should be dispelled and the internet should be seen as a tool for praxis rather than praxis itself.

- How can anti-imperialism stay anti-systemic? Without strong organization and ideological discipline, solidarity organizations can tend towards a reformist approach or be easily co-opted. Movements can centre on performative actions that attract online attention in the name of funding and neglect the underlying systemic action needed to defeat capitalism and imperialism as global structures. Unfortunately, solidarity organizations can never match the organizational and financial capacity of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), well-funded organizations that tend to co-opt radical political activism and deprive it of any anti-capitalist content, a process known as NGOization.[23] NGOs which derive their funding from foreign sources import their own form of imperialist ideology, promoting reformism and bourgeois self-interest over anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism. NGOs create a dependency where workers and activists begin to rely on funding that comes from wealthy sources disinterested in anti-capitalist agendas. In the process, workers’ movements lose their anti-systemic nature. There are, increasingly, accounts of “sell-outs” from the workers’ movements. NGOs can tend towards paternalistic, “white saviour” mentalities that deprive workers in the global South of any agency. NGOs are not the vehicle of anti-imperialist action and should not dominate within a solidarity campaign; bourgeois individualism, reformism and donor reliance should be avoided.

- How do we bridge transnational divides? A popular debate within Marxist studies of imperialism questions whether workers in the global North can even have solidarity with those in the global South, when the unequal exchange thesis argues the former benefit from super-exploitation of the latter. This long-standing debate on whether workers in the global North constitute a “labour aristocracy”[24] has no easy answer; all the debate makes clear is that a transnational divide must be overcome. Trust is the very core of solidarity; trust can be built by committing to a liberation struggle fighting the imperialism of one’s own country, and asserting the common interest of the proletariat against imperialism. Going back to the debate about whether communists should engage in critical support for anti-colonial struggles, for instance, Vladimir Lenin asserted that:

the age-old oppression … by the imperialist powers has not only filled the working masses of the oppressed countries with animosity towards the oppressor nations, but has also aroused distrust … even in their proletariat … It is therefore the duty of the class-conscious communist proletariat of all countries to regard with particular caution and attention the survivals of national sentiments… among nationalities which have been oppressed the longest; it is equally necessary to make certain concessions with a view to more rapidly overcoming this distrust and these prejudices.[25]

This is a necessary balance to strike: while giving sympathy to the anti-colonial sentiment that may strike more orthodox Marxists as “vulgar”, we can also advance a materialist, socialist analysis by directing this sentiment against imperialism. Additionally, trust can never be built from paternalism or fetishism. We can make political contributions without ever claiming to speak for the oppressed or telling them how to conduct their struggle; simultaneously, we can avoid depicting those in struggle as “pure subjects” incapable of doing wrong. Respecting agency necessitates treating political actors as three-dimensional subjects who deal with contradictions. We can look to Lenin again for a possible answer to this debate: a revitalization of the theory of “proletarian internationalism”, which Lenin says “demands… that the interests of the proletarian struggle in any one country should be subordinated to the interests of that struggle on a world-wide scale”. As we will see in this analysis, when the proletariat (in the global North or South) support the struggle against super-exploitation in South Africa, they act on a common interest to overthrow imperialism on a worldwide scale.

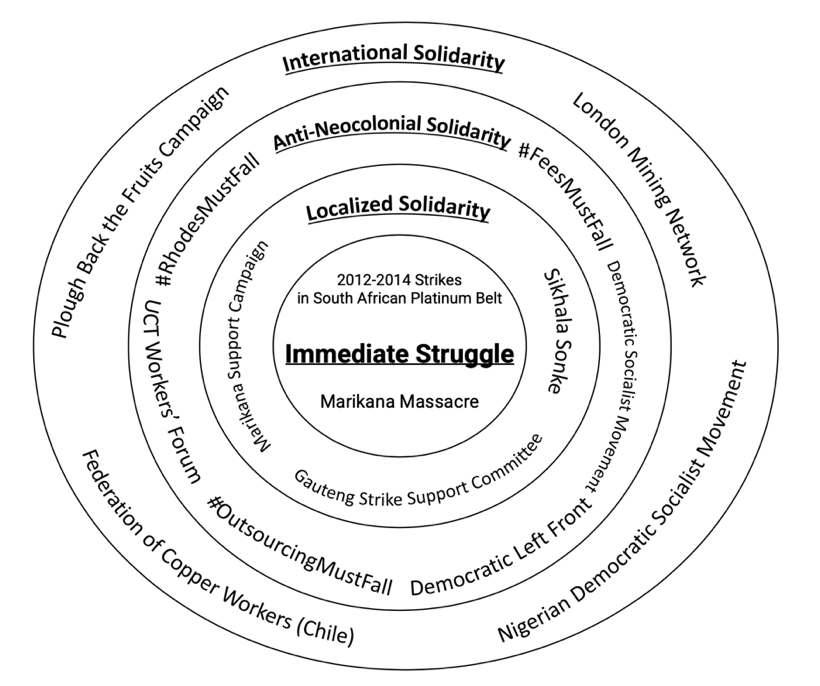

One of the goals of this writing is to determine whether post-Marikana activism serves as a viable model for creating anti-imperialist solidarity on a transnational, anti-systemic basis in the conditions of the 21st century. This reflects a desire to engage with all these critical debates, many of which played out in the aftermath of the massacre within the international solidarity network that sprang up to achieve justice for the 34 murdered miners. The actions of workers, students and activists within this network, in South Africa and across the world, can be seen as seeking justice along the supply chain, acting against the international corporations and neocolonial state that bore responsibility for the killings. Analysing a decade of action galvanized by this struggle, we can reflect on how this international network of solidarity contesting imperialism was born from the bloodshed. We can frame the diffusion of solidarity for a struggle on a localization-internationalization spectrum, where critical support begins within a community, extends throughout a country, and eventually reaches an international level, with all supporting one another. We will trace how support and solidarity for Marikana, and for the struggle of mineworkers against super-exploitation at the site of platinum extraction, diffused along this route.

The “localization-internationalization” spectrum of Marikana solidarity

1. Localized solidarity: the struggle in Marikana and South Africa’s platinum belt

Anti-imperialism must begin at sites of struggle and of extraction, as this is the location of super-exploitation. Here, we’ll trace how the first wave of solidarity developed within the local context of Marikana and the surrounding region, home to the world’s platinum resources. The massacre happened within the context of strikes in South Africa’s platinum belt; the strike against Lonmin had begun in January of 2012. When the massacre occurred, solidarity began within the immediate community of Marikana, the informal settlement next to the mountain where the massacres took place. After 34 workers had been murdered in cold blood, the very first people to extend solidarity were the women of Marikana. The day after the massacre, 17 August, women “gathered next to the site of the massacre in protest [against] mine exploitation” and were “confronted by the police and forcefully removed from the area”.[26] As Asanda Benya explains, women were also reacting to their own exploitation by imperialists via “invisible labour”[27] that allows more relative surplus value to be extracted from mineworkers. By the end of 2012, widows would form Sikhala Sonke (We Cry Together), a solidarity organization that would play a major anti-imperialist role later. This reflects a method by which solidarity and support were expressed for Marikana. Activists from within and outside the community organized and went to the site of struggle to provide the immediate support the workers needed.

In the aftermath of the massacre, the next step in the localization of solidarity was the formation of an organization to support the workers, who continued to strike for another month. Luke Sinwell describes the origins of the Marikana Support Campaign (MSC).[28] What was initially called the “Justice Now for the Marikana Strikers and Communities (ad hoc support group)” led a picket at the Gauteng South African Police Service Regional Command on 20 August, 2012, “which focused on police brutality and the 34 killings”. Two days later, “a public meeting bringing together about 150 worker and community leaders from Marikana as well as community-based organizations took place at the University of Johannesburg … The Marikana Solidarity Campaign (MSC), as it was then called … was launched”. The MSC describes itself as a solidarity group that

helps to fund legal representation for the families of those affected by the massacre and provides support to the widows and children of the slain miners. The campaign helps to organize and support protest action in Marikana and across the country and produces campaign materials, T-shirts, badges, and leaflets to ensure that Marikana is not forgotten.

Rehad Desai, who became a spokesperson for the MSC, described its origins:

Some people on our Facebook [pages], we set up a group and we realized a lot of people were also very angry about the shooting, very shocked …. We decided to launch the campaign … It’s really a single-issue campaign and the issue is justice for the Marikana miners, for those that were killed. Justice for their families so they can get some compensation from the police, from the government. Prosecution for the police and dropping of charges for the 270 miners arrested.

Several of the activists affiliated with the MSC were deployed to Marikana immediately after the massacre to help coordinate the birth of solidarity. Bheki Buthelezi is one such incredible example. He arrived in Marikana the day after the massacre. Explaining his motive for going to Marikana, Bheki demonstrated how solidarity begins through establishing commonalities:

Seeing that the workers were on strike too, you can see that there was a link between our struggles as a community and workers. [We are all] complaining about the injustice in our society… the same workers that were struggling are complaining about the same conditions that [my people] are living under.

Bheki was also cognizant of the contradictions of solidarity. He immediately perceived the hostility of the workers to outsiders pouncing on the massacre. In an interview with Sinwell, he noted that

after [the] massacre… it was not easy to communicate with anyone because the workers were angry at everyone who is [an] outsider … we were even pushed out of the informal settlement by the same workers [we were trying to assist] because they regarded us as a spy … so there was no trust between us and them, especially from the side of the workers.

Over time, because of his commitment, Bheki “became a respected worker leader”. As he said, “I was never a mineworker, but now I am a mineworker.” Sinwell notes that “on several occasions, [Bheki] was selected to act as a representative of the workers when speaking directly to management and other authorities”, so deep was the trust for him amongst the striking mineworkers. Bheki also made great sacrifices for solidarity, as he noted: “I left my family and risked my life to become part of the struggles here.”

With Bheki’s assistance, the MSC began to engage in critical support for the ongoing strike. On 29 August, Bheki delivered 2500 posters with the name of the organization, “Marikana Solidarity Campaign” and the names of the 34 mineworkers who had been killed, as well as T-shirts that read, “Remember the slain of Marikana”. However, Bheki would also have to negotiate bridging trust between the workers and the solidarity organization. As Sinwell details, there were encounters where the workers demanded the MSC change its approach. The MSC was able to be dynamic and not risk breaking the solidarity largely because workers informed its approach. For example, the name of the organization itself was in contention: Marikana workers told Bheki to “go back with these posters and change the name solidarity, instead put ‘support’ because the [name] ‘solidarity’ is … the name of another union … so now if you hand over these things you are breaking up the relationship that we wanted to build with you”. The MSC began to provide legal support to 270 arrested mineworkers, helping them to obtain representation when they were denied it by the state. The MSC also continued to protest and began to play a critical role in supporting the widows of the Marikana mineworkers. On 23 September, 2012, the MSC helped with a protest of women in Marikana.

The MSC would continue to protest long after the massacre. On 16 August 2013, the MSC spearheaded the one-year commemoration of the massacre. To plan the commemoration, on 8 August 2013,

alongside a number of former worker committee members, [the MSC] had a small meeting in a church in Pretoria to discuss how to proceed, and it was determined that the focus of the day [16 August] should be commemorating those who were killed while simultaneously continuing to demand a living wage of R12,500.[29]

This commemoration was attended by “at least 10 000 workers”. This established a custom of hosting an anniversary commemoration each year. The MSC also “began to plan a march to Pretoria (which was to take place on 12 September)”. The MSC “paid R1000 to have two cars patrolling around Marikana to alert people that there was going to be a mass meeting that day (11 September 2013) and a march which was intended to include all of Lonmin the following day”. This meeting was also attended by thousands of workers. The MSC “created a pamphlet which was distributed at the mass meeting”. Bheki recalled that this pamphlet “was ringing in the minds of the workers”.[30]

The MSC would engage in many other protests and actions to highlight the role of imperialism and neocolonialism at Marikana. One important action was the disruption of Ramaphosa’s testimony at the Farlam Commission. The protest, organized by the MSC, saw protestors chanting “Blood on his hands” and calling Ramaphosa a “liar” and a “sell-out”.[31] The MSC also continued to stage pickets in support of the charged mineworkers, such as a 31 July 2017 protest at the Rustenburg Magistrate’s Court as the state trial against 17 of the Marikana strike leaders began.[32] This demonstrates that the MSC continued its support for the Marikana strikers long after the cameras had left the scene of the massacre. The MSC began to advance an analysis of imperialism and neo-colonialism almost instantly to help South Africans and the global community interpret the killings. In a 3 September 2012 statement, the MSC condemned the government’s attempt to “demonize the victims of the massacre and excuse themselves and their masters, the mining capitalists… The responsibility for the massacre lies squarely with the Lonmin bosses and with the government”.[33] The MSC also argued that imperialist mining corporations were responsible for “the apartheid-like conditions in which mineworkers continue to live and work” and argued that “the Chamber of Mines is morally culpable for the crisis”. In a 2014 statement, the MSC endorsed the notion of a collusion between the state and imperialist actors, placing “the responsibility of these murders on political interference and collusion between the state and Lonmin”. Specifically, the MSC blamed Cyril Ramaphosa, holding him responsible for the massacre and supporting efforts to hold him liable, arguing that “he chose to protect his business interests and the interests of white monopoly capital in the most vile and aggressive manner”.[34]

One week after the Marikana massacre, on 23 August 2012, the leaders of the Marikana Support Campaign pledged “to give solidarity to workers in the platinum industry willing to advance solidarity strike action and a general strike”. After the massacre, on 8 September 2012, leaders unified workers across all the Anglo-American Platinum shafts – about 70 000 workers – and began to mobilize for a general strike in the platinum belt. This strike was seen as connected to the massacre at Marikana. As one branch leader commented: “This strike … started at the moment when our brothers were massacred by the police”. In response, the MSC helped launch a National Strike Committee in Rustenburg on 13 October 2012, “attempting to coordinate the major strike actions taking place across the entire country”. After firing 12 000 striking workers,[35] Anglo-American would end the strike on 13 November 2012 with a salary adjustment of R400 ($50). Two years later, workers in South Africa’s platinum belt, dominated by imperialist corporations such as Anglo-American, Lonmin and Impala, would initiate the longest lasting strike in South African history,[36] taking forward the wage demands of the Marikana strikers. The miners caused platinum production to fall by 26% in 2013/14,[37] one of the most significant anti-imperialist actions in the 21st century. Activists involved in the MSC established the Gauteng Strike Support Committee (GSSC). As Sinwell notes, “External agents intervened to provide solidarity at a critical time when money and therefore food and other basic necessities were scarce.” The GSSC and MSC network began to provide critical support to the strikers. Sinwell notes that:

by May (2014), building upon food collections initiated by two students at the University of Johannesburg (UJ) … the GSSC had developed a plan to collect food and money outside malls, in communities (such as Soweto) and at universities (including Wits and UJ).

A GSSC meeting on 18 May 2014 revealed that “the delivery of food by the University of Johannesburg team over the weekend boosted [workers’] morale”. When strike funds could not be used, money would “be deposited into the Marikana Support Campaign account and all the money would be used for food”. The ties of solidarity that the MSC activists had established would help distribute the food:

As collections intensified, 17 different shafts in the platinum belt were identified, and mineworkers from each shaft were selected as leaders who would be responsible for distribution. The GSSC relied on the pre-existing informal networks that the [MSC] had built with mineworkers over a period of nearly two years.

After the strike initiated in January 2014 had lasted for five months, the strikers were approached with an offer of an R800 ($74) increase. After so much struggle, the workers refused to settle for this pittance. As Bheki Buthelezi recalled, “Workers were literally crying when they heard that offer, saying the shafts should rather close and the companies go back home.” When union leadership took the offer back to the workers, the response was summarized by one worker: “We need to kill this leadership.” S.K. Makhanya, a worker leader, said, “I think that’s where the company has realized … the workers, they won’t retreat. One day after, they put a better offer of R1000 on the table. That’s where I realized the workers they may not be educated [but they know how much their labour is worth].” The strike ended with an agreement to increase pay by approximately R1000 ($92) a month (about 20%) in 2015, and a minimum salary of R8000 ($750) a month. Though the strike had succeeded in demonstrating the power of the workers and achieved a modest wage gain, the underlying structure of imperialism was left intact. Makhanya offered a succinct explanation of how imperialism persisted after the temporary victory of a wage increase:

We didn’t win the struggle of the working conditions. We’re still working [and] living in the condition where it’s not good for the human being. We are still living in the shacks, in the squatter camp, but we are producing the platinum – 80% in the world. So that’s why I am saying … maybe we have achieved 20% increase, but … we still have a fight, we still have a long way to go as the mineworkers.[38]

In an interview, I asked Bheki how workers in these monumental strikes had interpreted the fact that they were fighting imperialist corporations. He told me that “the radical, young” worker leaders in the “worker committees, they knew that they were against the imperialist Anglo-American [and] Lonmin… they knew that though they are registered under the Johannesburg stock exchange, they are in America and England”. Though he asserted that the “majority of workers were not in that mindset”, he detailed how some left-wing professors came to the strike and spoke to the mineworkers “in the language that we wanted… in order for workers to understand that even South Africa itself is not run in the best interest of the working class of the country itself”. Bheki told me that these workers were calling for “socialism… as a way of life”. In this way, workers had their eyes on the ultimate goal, even if it could not be achieved immediately. The nature of imperialism and its contestation by the most exploited workers in the world led Gavin Capps to describe the insurgency in the Rustenburg platinum belt as a “local battle in a global wealth war”.[39] Indeed, this first wave of activity was the localised form of struggle. But soon, a multitude of new movements, guided by students, and all pointing to Marikana as their inception point, would spring up in anti-imperialist solidarity, all focusing their anger on the imperialist, neocolonial system dominating South Africa. As Sinwell predicted at the close of his book, “the spirit of Marikana – which is defined by independent working-class power – will continue to reverberate in the lives of South Africans, in both communities and workplaces, for many decades to come”. This absolutely came true.

2. Anti-neocolonial solidarity: the spirit of Marikana diffuses throughout South Africa

The next leap in solidarity came as workers, activists, and students throughout the nation connected the struggle of Marikana and the miners in the platinum belt to their own struggles against neo-colonialism under the post-apartheid capitalist state. Post-apartheid political movements fighting neo-colonialism interpreted the massacre as evidence of collusion. Two days after the massacre, Julius Malema, formerly a youth leader in the ruling party’s youth wing who broke off to form the Economic Freedom Fighters, condemned the shootings, attacking the mine’s British owners and Cyril Ramaphosa and saying that “the government eats with the British … they killed you because Cyril has stake”[40]. Lindela Figlan, the vice-president of Abahlali baseMjondolo, a shack-dwellers movement, argued that “the time when [the government] was on the side of the workers has passed … [it has] aligned itself with the bosses and with imperialism”.[41] The National Union of Mineworkers of South Africa (NUMSA), which had taken one of the hardest stances against the killing and was expelled from COSATU (the Congress of South African Trade Unions, allied with the ruling party) afterwards, centred anti-imperialism as a response. Speaking to the Cape Town Press Club in 2014, NUMSA’s general secretary, Irvin Jim, pointed out that “at Marikana, the armed forces of the state mowed down workers who were demanding a living wage from an international mining company, Lonmin”.[42] Jim also pointed out that “the same happened during the farmworkers’ strike in the Western Cape”, demonstrating the beginning of connections being made between struggles within South Africa. Trevor Shaku, the national spokesperson of the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU), a new trade union federation formed of those unions that left COSATU in response to NUMSA being expelled, argued that “the Marikana Massacre could have been averted because Lonmin could afford to pay the wages demanded by workers at the time … Trade unions, students and other working-class organizations must organize to resist imperialist theft in the form of illicit financial flows and capitalism as a whole”.[43] This would come true: these new national political movements would advocate justice for Marikana to challenge the post-Apartheid government’s neocolonial collusion.

Students, outraged by the failure to achieve the promises of the anti-apartheid movement for their generation, launched movements in the spirit of Marikana to challenge neocolonialism at a national level. The #RhodesMustFall (#RMF) movement, originating at the University of Cape Town on the other side of South Africa in March 2015, which grew out of the experiences of students in post-apartheid society, expressed solidarity for Marikana and anti-imperialism (which was literally represented in the movement to tear down a statue of arch-imperialist Cecil Rhodes). In the #RMF manifesto, student leaders wrote that the statue of Rhodes “is a glorifying monument to a man who was undeniably a racist, imperialist, colonialist, and misogynist”.[44] But the movement was not simply about toppling a statue: it was about targeting a system that oppressed students and workers. In solidarity with the campus workers, RMF student leaders demanded the university “implement R10,000 pm minimum basic for UCT workers as a step towards a living wage, in the spirit of Marikana”. Soon after #RMF exploded at UCT, another movement challenging the effects of neo-colonialism and neo-liberalism began at Wits University in Johannesburg. #FeesMustfall began as a movement against high tuition fees, but slowly turned into an uprising of young South Africans. Some students involved in #FMF had a clear understanding of what they were going against in South Africa. Phetani Madzivhandila, who was part of the political education task team of #FMF at Wits, later told me that South African students were facing a situation produced by the “consolidation of the comprador bourgeoisie who are assisted by the metropolitan bourgeoisie in the exploitation of the workers. The murder of the workers at Marikana … is the hallmark of … the state of neocolonialism”.[45] Some students (unfortunately, not many) also insisted that their struggle be turned into solidarity for super-exploited campus workers. They helped support the ongoing #OutsourcingMustFall campaign against sub-contracting of workers, rallying behind existing worker-student alliances that preceded Marikana. The students involved in the campaign expressed the common sentiment that “we can’t allow this exploitation of our parents to go on. This outsourcing must end.”[46] As was the case with Marikana and the platinum belt strike, “alternative organizations and structures to unite workers and to build solidarity for workers within the university community … include the UCT Workers’ Forum, the Wits Workers Solidarity Committee and the UJ Persistent Solidarity Forum”.[47] These alternative organizations attempted to revitalize the worker-student alliances needed to challenge post-apartheid neocolonialism, with mixed success.

Solidarity organizations such as the UCT Workers’ Forum specifically pointed to Marikana as a rallying point for their activism. Thanks to the influence of politically conscious workers, students, and academics, the Workers’ Forum often invoked the spirit of Marikana in its initiatives. During the Marikana strike, the WF wrote this:

We say to the striking workers of Marikana: we greet you and stand with you. Forward with your strike. Forward with your demand for R12,500. We call on all workers everywhere: stand with the striking workers of Marikana. Join the strike in solidarity. Take forward the struggle for R12,500 minimum for all workers everywhere.

They wrote,

To the workers of Marikana. You are there at the front of the struggle of all workers … you have shown every worker what is possible when workers stand together, the revolutionary strength of the working class… you are fighting bosses that… draw on resources of stolen money over generations, from across the world. They do not stop at the borders of the mine to get their strength to fight you.

The WF asserted that “workers cannot stop at the borders of Marikana. With the workers of Marikana we turn to all other workers. We must strike together in support of them”.[48] Johnathan Grossman, an activist with the UCT Workers’ Forum (as well as the UCT MSC), viewing these struggles in totality, wrote that “student mobilizations … through direct action, disruption and interference bringing, [like the] workers at Marikana… a new experience which is allowing workers to build a resurgent confidence in themselves, their class and their capacity to collectively create solutions with trustworthy allies in struggle. It is best called the spirit of Marikana – not just a commission, a massacre or a tragedy, but the grounding of a workers’ future”. Grossman critically pointed out how the common conditions of Black campus workers and Black students from working class backgrounds were opening “the door to solidarity and generosity of sharing between workers and students in struggle”. Grossman concluded that “the student movement is enriching it with a totalizing vision of decolonizing, bringing a resurgent vitality to the student worker alliance”.[49] These solidarity groups would bring in other workers from outside the mining industry to provide solidarity.

Efforts were made to get poor South Africans all over the nation to see what they had in common with those in Marikana. In 2017, a protest outside South Africa’s parliament in Cape Town for the five-year anniversary of Marikana demonstrated how solidarity had travelled across the entire country.[50] Workers from the townships (low-income residential areas on the edges of towns and cities, historically for segregating Black people) of Gugulethu and Khayelitsha, outside Cape Town, attended in support of Marikana workers and emphasized the common situation they faced with the poor there, just as Bheki had. The “spirit of Marikana” diffusing throughout the entirety of South Africa shows how a localised struggle takes on nationwide appeal when commonalities are identified for workers, students and activists from different communities.

3. International solidarity: global South commonalities, resistance within the imperial core

The broadest level of anti-imperialist solidarity would take place at an international scale. This was initiated in response to the local/national solidarity springing from South Africa. On 29 October, 2012, just more than two months after the massacre, the Marikana Support Campaign published “An Urgent Call for International Solidarity”. In it, they called for “a coordinated national and international campaign that presses for a just outcome for the Marikana families of the deceased, the scores injured, and hundreds arrested”.[51] In a 2014 interview, Trevor Ngwane, one of the leaders of the MSC, was asked by Jakob Krameritsch about international solidarity for the MSC. Ngwane replied:

One of our inspirations, even when we were fighting against apartheid, was the support we got from the anti-apartheid movement … we want to have an international campaign against Lonmin in London and in Europe. There are also a handful of other companies who benefit from platinum in South Africa, and they should be included into this campaign.[52]

The MSC consistently had a view to create a transnational network able to fight for the Marikana miners and challenge imperialism in South Africa. The reaction was immediate across the world: on 23 August, 2012, the MSC expressed gratitude for “all statements and acts of solidarity such as those by the Labour Party of Pakistan and workers in Oakland, California” and encouraged “progressives in the world to actively demonstrate their solidarity as they have done outside South African embassies in Spain, New Zealand and Ireland thus far”.[53] During the New Zealand protest, protesters attacked the South African High Commission with paint bombs, saying “Blood on your hands!”[54] In Ottawa, the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers’ Union of Canada protested. In London, 50 protesters picketed Lonmin’s Hyde Park offices and the South African consulate. The protesters erected signs that read: “Economic apartheid is alive and killing”, as well as “Mining companies are thugs that don’t care about humanity”.[55] A second anniversary protest at the consulate in 2014 drew support from a truly transnational network comprised of the Caribbean Labour Solidarity organization, the Pan-Afrikan Society Community Forum, the All Afrikan People’s Revolutionary Party, the Pan-Afrikan Reparations Coalition in Europe, the Colombia Solidarity Campaign, the Algeria Solidarity Campaign, the Tanzanian Moyo Wa Taifa and Foil Vedanta, an organization against the British-Indian mining company Vedanta Resources.[56] The MSC established a tradition of protesting Lonmin in London, with protests at the Lonmin Annual General Meeting taking place until 2019. At all these protests, organizers emphasized Lonmin’s imperialism, with an affiliated group, the London Mining Network, calling in 2019 for those in solidarity “to act and join frontline communities resisting British mining and financial imperialism in demanding justice and reparations for Marikana”.[57]

Activists with the MSC drew attention to the “value chain” of exploitation from Marikana. This was epitomized by the actions against BASF. Marikana was so central in BASF’s supply chain that activists deemed it “co-responsible for the massacre”. Activists launched the transnational campaign Plough Back the Fruits in 2015, a title coined by the widows of the mineworkers to represent their demand: “Give us back our rightful share of wealth and prosperity!”[58] The activists note that this “demand is directed towards the global North in general, [but] BASF as a corporation sits at the very heart of this campaign”. In 2016, Ntombizolile Mosebetsane and Agnes Makopano Thelejane, widows of slain miners, undertook a speaking tour in Europe exposing BASF’s “supply chain responsibility”. The widows presented “body maps” of the murdered in Vienna as part of the tour. The tour ended on 29 April at the 2016 BASF shareholders’ meeting, where Mosebetsane and Thelejane explained that they had come “to tell you of what is happening at the far end of your platinum supply”. They demanded that BASF “establish a trust fund of eight million euro, to help improve our desperate situations”. On 12 May 2017, at the next shareholder meeting, Mzoxolo Magidiwana, a mineworker at Marikana who was shot nine times and is known as “dead man walking”, said:

It is my understanding that BASF is buying platinum from Lonmin for millions of euros per month; I therefore believe that what we, the workers, are asking for is not unreasonable. We know that the management of Lonmin and BASF are making huge profits; we know that we dig out one of the most precious metals on earth – we just want to live in dignity – I cannot see that this wish is unreasonable. I ask you, the CEO of BASF, Kurt Bock, to answer me: is this too much to ask?

The reaction of BASF’s leadership was that it is too much to ask: Bock made it clear that BASF regarded Marikana as a domestic problem for South Africa, saying “these things have to be sorted out in your country first.” Bock, “visibly irritated”, attempted to defend BASF and Lonmin’s relationship as altruistic, saying “We could purchase from another supplier. We don’t have to work with [Lonmin]. But if we don’t work with them, there will quite literally be over 10 000 people out on the street. Is that really what you want?”

Sikhala Sonke activists such as Thumeka Magwangqana would play a major role in putting anti-imperialism on the agenda. In 2015, they lodged a complaint against the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s private investment arm.[59] Of the $150 million invested, $15 million was “specifically earmarked to improve the lot of communities around the mine”. As the women explained, “more than seven years after the commencement of IFC funding, living conditions for the communities around the Marikana mine are dire”. In fact, this money was instead diverted to Lonmin’s general account. The women protested to the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), the World Bank’s “independent” overseer. They cited “an absence of roads, sanitation, and proper housing, as well as accessible, potable, and reliable sources of water… The complainants … allege failure by Lonmin to provide … adequate health and educational facilities which were promised at the inception of the project.” The CAO concluded in 2017 that the IFC would be investigated for failing to ensure Lonmin complied with its performance standards, but this represented the World Bank investigating itself. As the World Bank imperialists revealed their unwillingness to punish Lonmin or themselves in any capacity, Sikhala Sonke gave up on this internal reformism, seeking new tactics. Magwangqana has travelled to the global North to fight the imperialists in their homes: in 2018 she travelled to Britain and Germany to protest the Lonmin AGM and BASF meetings. She said of her efforts that Sikhala Sonke “want reparations to be paid to the widows and the mineworkers who were injured during the massacre, and we want Lonmin to take full responsibility”.[60]

Workers in the global South forged solidarity out of their own encounter with imperialism and repression by the neocolonial state. The Brazilian Centre of Solidarity with the People “vehemently repudiated the cowardly murder of the mine workers of platinum company Lonmin PLC” and declared that the SA government had been exposed as an “oppressive, violent and murderous state”[61]. In Zimbabwe, activists such as Tafadzwa Choto worked with the International Socialist Organisation to organize meetings with unions and attempted to organize marches on the South African embassy; these were, however, blocked by the Zimbabwean government. In some actions, the connection to local experiences was made explicit.[62] In Nigeria, members of the Nigerian Democratic Socialist Movement protested at the South African High Commission in Lagos on 6 September 2012 “in solidarity with Lonmin miners and their demand for better pay”. Dagga Tolar, the publicity secretary of the Democratic Socialist Movement, “drew a parallel between the Marikana massacre and deployment of soldiers and tanks by [the] Goodluck Jonathan government at the facilities of PHCN [the public electricity company] in Nigeria to suppress the protest of electricity workers as it prepares to enforce privatization of the company”.[63] In a statement, Segun Sango, their general secretary, condemned “the massive exploitation in the mining sector wherein miners are condemned to poverty despite creating profit for the multinationals and the top government officials” and demanded “the nationalization of the mining sectors”. Connections have been made to the oppression suffered at the muzzle of imperialist weapons. As Imraan Buccus pointed out, “the semi-automatic G3 rifles that the police used in the Marikana massacre in 2012 were manufactured by South African arms manufacturer Denel under license from Israel”.[64]

One of the most important moments of solidarity came from Chile, where a 2018 statement drew a parallel between shared conditions. In a letter to the London Mining Network, Miguel Santana Hidalgo, vice-president of the Confederación de Trabajadores del Cobre (Copper Workers’ Confederation) identified that the practices of Lonmin “continue to be allowed and supported from London. The large transnational capitals do not recognize ethical values… and have always been allowed to buy government agents to give them access to exploiting raw materials, under bad working conditions, leaving only pollution for our countries”. Hidalgo identified shared conditions in South Africa and Chile. He noted that:

here in Chile, Anglo American, the same company that in the context of the South African strike of 2012 fired 12 000 strikers only to rehire them for just 177 euros, has been … persecuting the more effective union of newly constituted contract workers at their Los Bronces site in Santiago de Chile … thus, as long as fomenting from London of this action by the companies is allowed to continue, we will continue lamenting that events like those that happened in Marikana continue repeating … To avoid this, the mining companies must begin by recognizing their responsibility and act accordingly to reach the truth and the necessary reparations, which are not only economic but spiritual as well.

Hidalgo concluded that “We will continue to find ourselves in this path of struggle”. Chilean workers connected their exploitation by Anglo-American to a globalized struggle alongside South Africans exploited by the same company. This is a significant instance of international solidarity because it demonstrates a “parallelism” where super-exploited workers in different parts of the global South can forge alliances based on observations of their shared oppression. This provides a path forward for creating sorely needed alliances of global South workers.[65] All these acts of solidarity helped demonstrate true proletarian internationalism for Marikana.

Diffusion of solidarity for Marikana throughout the world

“Meet the new boss, same as the old boss”: Marikana, ten years later

As we reflect on the magnitude of these campaigns, across South Africa and the world, we are left to lament that super-exploitation remains as the structure of imperialism, and neo-colonialism remains virtually unchanged. But this cannot be blamed on the campaign. We must examine the enormity of the enemy, and the capital that came in to protect super-exploitation when it was challenged in 2014.

After the 2012 to 2014 strike wave, Lonmin continued a strategy of massive over-production and rapid exporting of profits. But the damage done to the firm by the strikes, which managed to cripple Lonmin’s platinum production, if only briefly, was severe. In 2015, Lonmin’s share value would fall by 99.3%.[66] The South African government failed to nationalize Lonmin at this cheap cost (as many trade unionists demanded), allowing Lonmin directors to instead approve the company’s sale in 2017. Lonmin preferred to be bought out at an undervalued price that, as Patrick Bond put it, was “understood as a rip-off of investors and workers”. In 2019, Lonmin was acquired by Sibanye-Stillwater in a $286 million takeover. The buyout by Sibanye was a dream come true for Lonmin. The 2019 deal was seen as a “lifeline for cash-strapped Lonmin”.[67] Lonmin CEO Ben Magara said at the time that Lonmin was “very appreciative” of the bailout. This sweet deal for Lonmin wasn’t great for the workers of Marikana. The deal had been “touted as the only way to save [Lonmin’s] 29 000-strong workforce”; instead of cutting 12 600 jobs, as Lonmin had planned, Sibanye-Stillwater cut around 5270 jobs, or about 6% of its workforce – no less catastrophic. Very little changed when Lonmin was acquired and incorporated into Sibanye. In Sibanye’s acquisition proposal, they readily admitted that there would be “no cancellation of any prospecting right or mining right held by a member of the Wider Lonmin Group” and further said that “Sibanye-Stillwater does not expect any material dys-synergies to arise in connection with the Acquisition”.[68]

Who are the new bosses? Sibanye, a South African firm, had acquired the American Stillwater in 2016, reorganizing its operations in both the US and South Africa. To facilitate the merger, Sibanye had secured a loan of $2.65 billion, underwritten by foreign finance capital from Citi, HSBC, Barclays Bank, Credit Suisse International and J.P. Morgan.[69] Upon acquisition of Lonmin, Sibanye–Stillwater became the world’s largest producer of platinum, second largest producer of palladium and third largest producer of gold.[70] Sibanye-Stillwater also bought Anglo-American’s platinum operations in Rustenburg, creating a quasi-monopoly over the platinum belt. Despite the name change, and Sibanye ostensibly being a “South African” company, the top ten shareholders in the company are all based in North America.[71] Sibanye-Stillwater operates no differently to Lonmin: in 2019, it had the highest fatality rate in the mining industry, with 20 out of the 45 mining deaths in South Africa in 2018 having occurred there.[72]

| Owner Name | Value of Shares Owned | Headquarters |

| Condire Management LP | $71,261,516 | Dallas, USA |

| AQR Capital Management LLC | $53,181,385 | Greenwich, USA |

| Van Eck Associates Corp. | $45,424,406 | New York City, USA |

| Sprott Asset Management LP | $43,610,314 | Toronto, Canada |

| Dimensional Fund Advisors LP | $41,145,383 | Austin, USA |

| Sprott Asset Management USA, Inc. | $32,929,650 | Carlsbad, USA |

| Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC | $30,076,591 | New York City, USA |

| Arrowstreet Capital LP | $27,073,005 | Boston, USA |

| Invesco Advisers, Inc. | $19,778,405 | Atlanta, USA |

| Susquehanna Financial Group LLLP | $17,092,969 | Philadelphia, USA |

Top Ten Owners of Sibanye-Stillwater by 2022

Conditions in Marikana have not fundamentally changed. Worse, the quasi-monopoly that Sibanye-Stillwater enjoys allows it to rule the platinum belt as a fiefdom. With little fear of any challenge from smaller firms, it can continue to impose super-exploitation and harsh conditions on the workers. Housing persists as a major issue in the community. Based on the World Bank agreement, before 2008/9, Lonmin should have already built more than 2000 houses for its workers. This number has still not been achieved today. Nevertheless, the World Bank’s IFC regularly bragged about Lonmin’s “developmental success”. The IFC’s 2010 claim that it had “helped transform the way the world’s third-biggest platinum miner operates”[73] was delusional. Unfortunately, the IFC was subsequently given a pass by the Farlam Commission, which “entirely ignored the IFC’s complicity, including the unfulfilled housing finance offer”.[74] Sibanye-Stillwater has not modified this situation whatsoever, and instead persisted with Lonmin’s negligence. Inhospitable living conditions persist in Marikana. During a visit to Marikana, I observed the number of loan businesses in the area, payday lenders or loan sharks (mashonisas in isiZulu), who typically take workers’ bank information as collateral for loans. Indebtedness is stark in the area. Liquor stores dominate the area; they foster alcohol abuse.[75] I was told that post-traumatic stress disorder is endemic and residents who heard or witnessed the massacre continue to suffer psychological distress. Inside the church in Wonderkop just across from the koppie that was the main site of the massacre, Thumeka Magwangqana told me that “the dying continues every day; it never stopped”. A 2006 statistic, that 77.3% of people in Marikana lived without cash income,[76] is unlikely to have changed much. The sole hospital in the area is only accessible to mineworkers; locals must find help far outside of the area. I was shown “recreational facilities” for youth in the area, such as a “tennis court” – with no net or paving. I watched as a bus full of workers arrived in the area. Many of them were arriving back from court, still facing charges ten years later. Primrose Sonti, one of the members of Sikhala Sonke and now an MP, told me that “instead of any improvement” conditions in Marikana are actually “worse than before”. She pointed to the worsening unemployment and lack of service delivery, particularly electricity, as evidence. She informed me that Sikhala Sonke members (now organizing as Sinethemba, isiZulu for “We have hope”) were attempting to conduct local farming for the community, mainly to help women deal with unemployment, but lacked any funds. Magwangqana also informed me that she had been asked to bring community support specialists into the area to help struggling women and children.

Ten years on, people in Marikana told me that Sibanye’s monopoly over the platinum belt has allowed them to engage in ever more egregious practices. Sibanye had announced, when buying Lonmin in December 2017, that it would accelerate the closure of Lonmin mine shafts to save more than $100 million annually by 2020. As a result, 38% of Lonmin’s 33 000 employees were due to be retrenched between 2018 and 2021.[77] Sonti pointed out that Sibanye-Stillwater hadn’t done “anything to help the community” and it was “all the same”. She lambasted Sibanye’s efforts to “memorialize” Marikana as egregious and hypocritical. This is a particular reference to Sibanye’s first Marikana Memorial Lecture in 2020, which they used to whitewash the violence committed against workers in 2012. They framed the lecture as a dedication to “our departed colleagues”, acting as if the murdered workers had mysteriously disappeared and were colleagues rather than super-exploited labourers. Sibanye’s memorialization of those “who died in the Marikana tragedy”,[78] and the assertion that Marikana workers “lost their lives”, reveals the hegemonic narrative: this was a “tragedy” rather than a massacre perpetrated by imperialists. Sonti noted that Sibanye’s “monument”, a plaque with the names of the murdered, is “in the gate of the offices of Sibanye, not even where the tragedy happened”. Sibanye claims to “create value for all stakeholders through the responsible mining and beneficiation of our resources”. It asserts that since its “acquisition of Lonmin … we have intensified engagements with many of our stakeholders at and around Marikana, especially with those most directly affected by the tragedy”. One of the ways Sibanye claims to do this is through the 1608 Memorial Education Trust, which claims to have “disbursed R8.9 million [$543k] in tuition, boarding fees, transport, uniforms and educational projects” for the families and children of the murdered miners.[79] Needless to say, this is a pittance compared to the salary of Sibanye CEO Neil Froneman, who “earned” a R300 million remuneration package ($19 million) in 2021 alone.[80] No matter the size of the bribe, however, Sibanye will never be able to buy off the workers and widows of Marikana to convince them to let bygones be bygones.

Resistance to these conditions, and to the imperialists in Sibanye-Stillwater, persist. A three month strike in 2022 in Sibanye’s gold operations recently ended in a three-year wage deal with an average 6.3% increase.[81] The strike was prolonged by the fact that Sibanye refused to give a raise of more than R800 for the lowest paid. Union leader Jeff Mphalele said, “I don’t know why denying the R200 is so important for the company. The CEO gave himself R300 million – 300 million for just one man!”[82] But Sibanye refused to accept these basic demands: “We will not be coerced into acceding to demands which are not inflation related, unaffordable and threaten the sustainability of our operations,” said Richard Cox, Sibanye’s executive vice-president of gold operations. Sibanye said in a statement that, although the company respects the rights of workers to strike, unions should reconsider their efforts “in the interests of striking employees who clearly do not support the strike”. Announcing the strike, unions accused Sibanye of being the “worst employer among workers … we will not spare any cent to relieve the workers from the shackles of Froneman. We will not allow him to continue to exploit our people by using the minerals that belong to the people … he is not the owner of the minerals.” Part of this action also saw thousands of workers occupy the grounds of the Union Buildings (South Africa’s seat of the presidency) to pressure the government to intervene in this strike.[83] Before that strike ended in May, the unions threatened to give notice of a secondary strike at Sibanye-Stillwater’s platinum operations, which would have included the Rustenburg and Marikana platinum operations. Miners at the platinum operations, where wage negotiations started in July, are demanding wage increases of 40%, from a R12,500 demand in 2012 to R20,000 in 2022. Those observing the negotiations have pointed out that PGM prices are rising again, and with them, profits for the mining companies. This makes Sibanye’s claims about being unable to afford a wage increase even more ludicrous. Behind the strikes and the wage demands is a consistent desire for real anti-imperialist action, which should take the form of nationalization. Dennis, a mineworker at the Union Building protest, argued “that even though [the strikers] believe that the mines should be in the hands of the workers and communities that are affected, they are merely at this point demanding salary increases to survive the current surge in living costs”. At some point, wage increases cannot be the only item on the agenda.

Meanwhile, people have continued to try to bring the culprits of the massacre to account. An increasing frustration among workers with the neocolonial government was revealed this year when striking gold miners booed President Ramaphosa at what was supposed to be a May Day rally in Rustenburg.[84] Ramaphosa was recently found to be potentially criminally liable for Marikana.[85] He condemned this “politicization” as “unfair targeting”. Meanwhile, workers have begun a R1 billion compensation court battle, and claims continue to be addressed by the government, with 300 having been resolved by now.[86]

Violence continues to claim the lives of activists involved in Marikana: Ntombifikile Mthethwa, formerly with Sikhala Sonke, was killed in a robbery on 27 June 20252 in Wonderkop.[87] Activists from Marikana travelled to attend her funeral in Flagstaff, in the Eastern Cape. The bloodshed continues in Marikana, and there is no sign that justice is around the corner. Bourgeois law will not hold the neocolonial state actors, much less the imperialists, to account. The struggle must continue.

Conclusion: reflections on an anti-imperialist solidarity, prospects and contradictions

So, in reflecting on ten years of activism and solidarity for Marikana, what innovations have been made in defining anti-imperialist solidarity? In the context of Marikana, one inquiry that addressed similar questions came from an article by Trevor Ngwane, a South African scholar-activist heavily involved in the Marikana Support Campaign, and Alexander Behr, also a scholar-activist involved in the campaign against BASF in Europe. In their article, “Postcolonial internationalism: thoughts on redefining global North–South solidarity in the twenty-first century”,[88] Ngwane and Behr deal with many of the questions that I have here mapped onto the post-Marikana solidarity campaign. Ngwane and Behr conclude that

solidarity-based actions targeting transnational structures of exploitation require communication to cross established borders and boundaries so we can learn about the demands of those others with whom we want to forge an alliance. We otherwise risk imposing our own views, needs and conceptions of the good life on other people, and thereby overlook the fact that responsibility has to be conceived as a dialogic process.

Especially important is the emphasis, similar to Lenin’s, on learning from and avoiding the historical patterns of engagement between colonizer and colonized, oppressor and oppressed. They conclude that “reflected through the prism of postcolonialism, then, solidarity would be about building communicative relationships that increase our sensitivity and acceptance of other, different, diverging perspectives, relationships that encourage us to listen actively”. We must only emphasize here that this is not an academic process. Anti-imperialist action requires this communication to play out on the frontlines of struggle, not sequestered in seminars and conferences. This risks turning reflexivity into a performative exercise rather than a living process created through camaraderie. Our conclusion must always be in favour of praxis over mere abstract theoretical exercises. We can take examples from the Marikana Support Campaign to see how anti-imperialist solidarity is forged out of committed action, not academic speculation. Bheki, for instance, demonstrated the application of all these ideas by living among mineworkers and truly becoming one of them. If we relegate anti-imperialism to performance or academia, we risk losing a fervent commitment to it when the cameras have left. In the lead-up to the tenth anniversary, activists from Marikana informed me that they are frustrated by “parachuting” (deploying to a community simply to obtain information for knowledge production, for instance) by many academics and activists. There is a feeling of betrayal and frustration among the people of Marikana, not just with the imperialist companies but with the activists who pledged to assist them. Turning the commemoration of Marikana into a routine on an annual basis can only serve performative ends; a never-ending commitment to struggle against imperialist interests that conduct their super-exploitation on a 24/7 basis is the only way to match the enemy and win the confidence of those we claim not to be fighting for, but alongside.

On 16 August 2022, South Africans marked ten years since the 34 miners were shot down at Marikana. At the site of the massacre, 5000 workers gathered, wearing T-shirts saying “10 Years of Betrayal”.[89] The union leading the commemoration, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU), issued a demand for a basic salary of R20,000 ($1250), and argued that foreign companies seeking mining rights in South Africa must contribute to the social development of communities where mines have been established. Commemorations across the country took place, including a film screening at the ongoing New Dawn Occupation in Kuyasa, Cape Town.[90] At Constitution Hill in Johannesburg, a poignant site for commemorations, a day-long symposium was held on 20 August and livestreamed across the world in collaboration with the University of Johannesburg Centre for Social Research and Practice (CSRP), Africa is a Country, and the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung in Southern Africa.[91] Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, a tenth anniversary vigil was held at the South African High Commission in London.[92] While recent surveys have shown that knowledge of Marikana is not widespread even in South Africa – only 40% of South Africans surveyed said they know enough to explain what happened[93] – these events reveal that the legacy of Marikana has not disappeared. The ten-year commemorations have put it back at centre-stage, and hopefully will revitalize the solidarity movement for Marikana.

The only conclusion we can speculatively draw here from a history that is still being (re)written is that internationalism and anti-imperialism are needed now more than ever. As Ngwane and Behr note, “there can be no doubt that the collapse of internationalist practice [at the end of the Cold War] was a serious political disaster”. The effects of neoliberalism have prevented a strong, sustainable anti-imperialist campaign from emerging. Marikana can never be read as one event that occurred on one day; Marikana is the process occurring to workers in the global South under imperialism day after day. But this leads us to revise Ngwane and Behr’s conclusion: internationalism from the global North has struggled in the post-Cold War world, but internationalism within the global South has always been rooted in commonality and the shared solidarity of the oppressed. Ngwane and Behr argue that “common interests between different groups of socially disadvantaged people must be found” to construct solidarity. We can look no further than the common interests between mineworkers of Chile and South Africa, struggling under the same bosses, to see the horizons of a new solidarity. As the authors of “Marikana: Voices” conclude, at Marikana, as throughout the global South, “workers’ agency and leadership is no obscure radical rhetoric or theory of ivory tower academics or non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Rather, it is the unfettered praxis of the working class – which could not be contained”.[94] When workers organically forge ties of solidarity, as the Chilean copper workers have with the miners in South Africa, no academic or NGO can match this. Similarly important, as Magwangqana noted throughout my interview with her, “We in Marikana want to tell our own stories”. The movement for anti-imperialism is empty without the voices of those who suffer from super-exploitation; no one can liberate them as a saviour, and their desire to tell their own story is part of a process of rewriting their own history and reclaiming agency. But, above all, the lessons from the Marikana campaign inform us that the future of anti-imperialist solidarity and support, while certainly facing many challenges and ambiguities, is full of opportunities. For South African politics, as for anti-imperialist politics throughout the global South, we are left to concur with Andy Higginbottom one decade on: “After Marikana: nothing has changed; everything has changed.”

Some topics and questions for group discussion:

- Why is it necessary to contest imperialism on local, national, and international levels by following the “value chain”? How does imperialism operate at all three levels? In the state of “neocolonialism”, why is it important to contest the “comprador” class within the global South?

- What were the tactics of the solidarity movement? What worked, and what did not? (Reflect on the embassy protests, complaint process at the World Bank, attending the BASF/Lonmin shareholder meetings, and so on).

- Reflect on the “parallelism” of the copper workers’ union in Chile with the Marikana miners. How does having a common oppressor (major mining companies) across international borders allow for closer solidarity between workers in the global South?

- How did activists from Marikana take their struggle to an international level? Reflect on Thumeka Magwangqana’s travels to Europe to bring a voice from Marikana to the global North, and how this helped those at Marikana tell their own stories.

- How did technology such as Facebook play a role in the activism around Marikana? What are the drawbacks of relying on technology?

- Why is it important that activists commemorate the Marikana massacre and promote an active memory of the event, in South Africa and beyond? How can there be “commemorations from

below” compared to the hypocritical “commemoration” at Sibanye-Stillwater?

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Luke Sinwell, Trevor Ngwane, Immanuel Ness, Terri Maggott, Claire Ceruti, Andy Higginbottom, Thumeka Magwangqana, Asanda Benya, Bheki Buthelezi, Primrose Sonti, Thapelo Lekgowa, Johnathan Grossman and others who helped provide opinions and feedback directly from the frontline of struggle for Marikana workers over ten years.

Addendum

After some very helpful feedback, I have decided to add a brief addendum with some key points for consideration that were omitted in the original.