(Image courtesy of the late, great Marc Rudin or “Jihad Mansour”, who passed away in April of 2023).

Introduction:

We must delve back decades to understand the present balance of things. The long struggle of the Palestinian people has taken different forms over this expanse of time, but in this multiplicity of forms there is one common aim: the liberation of Palestine. The joy when the Apartheid wall is knocked down and crumbles to dust, when checkpoints and transit IDs obtain obsolescence, when water, olive trees, hillsides, sacred gardens all return unencumbered by occupiers. This is a dream that one day will be reality. For the people who suffered that oppression which gave us the word “Apartheid”, it seemed a long dream for the day when hated checkpoints would give way to free movement; but the continued motion of the struggle in South Africa has today led to a genocide case which has given the world, and the rest of the Global South, much hope, and revealed that the edifice of Western hegemony is crumbling, along with all its Apartheid walls.

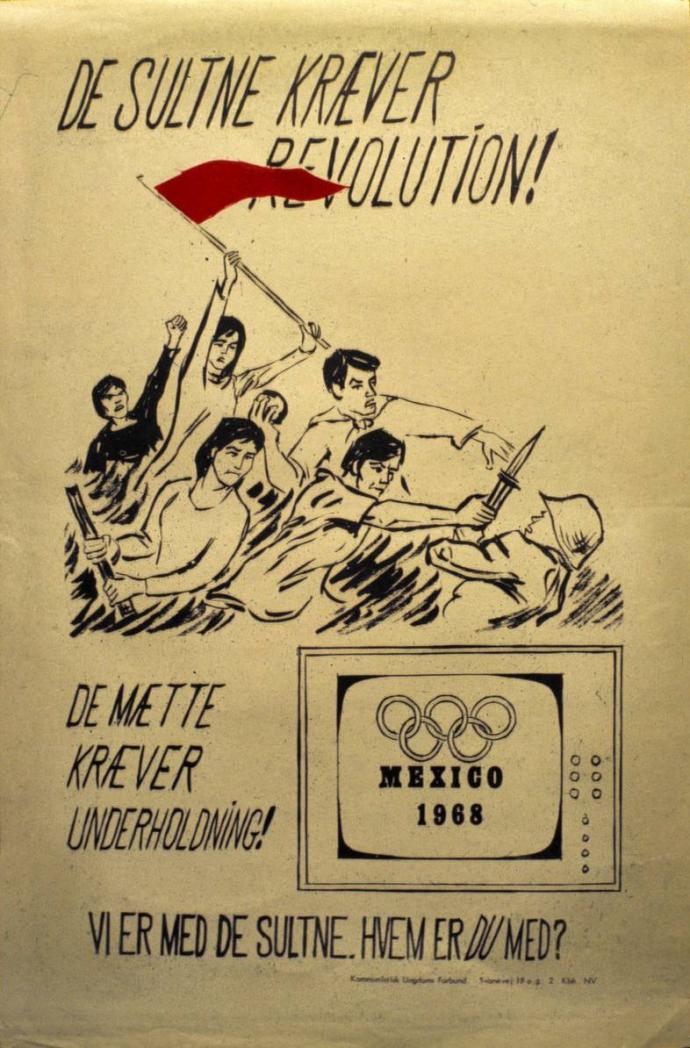

Torkil Lauesen and members of his organization, along with others of their generation of anti-imperialists, fought Apartheid in South Africa and Palestine, not just with words or legal decrees. The aid that the KAK/M-KA[1] (whether “legally”, through fronts like Tøj til Afrika, or “illegally”) gave to movements both in and around South Africa, such as the MPLA in Angola and the Isandlwana Revolutionary Effort[2] amongst the South African diaspora were the most advanced expressions of solidarity from activists in the imperial core. This support helped make Apartheid a dying beast in Southern Africa, but it is still alive in Palestine.

It was with a group in Palestine and amongst the Palestinian diaspora that his comrades would contribute to another front in the anti-Apartheid struggle. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine became a partner alongside the Danish anti-imperialists who (unlike others in the European Left who sought Palestinian support to aid their own fantasies of Revolution in the imperial core) desired that the exchange should go the other way, and committed to supporting the PFLP with money and weapons obtained illegally, robbing money-in-transit vehicles and more[3].

The PFLP represented not just a uniquely Palestinian vision of liberation, but an internationalist organization that sought to “engulf the entire Arab world from Syria to Morocco” with a “socialist future”. This vision of emancipation spread beyond the Arab world; as Lauesen notes, “the PFLP had a strong internationalist outlook. It allowed liberation movements from around the world to use its facilities. During my visits, I saw Kurds, Turks, Iranians, South Africans, and Nicaraguans. In other words, supporting the PFLP meant to support many liberation movements.”[4] That South African revolutionaries, trained by their Palestinian counterparts, should today play a major role in the Global South’s opposition to Israeli apartheid and American hegemony, is the fruit borne of internationalism and solidarity.

Though the M-KA’s practical support for the PFLP ended in 1989, and the activities of the organization have less volume compared to the Cold War era, the Palestinian struggle has decisively resisted the era of American “unipolarity”, and so too have the visions of the PFLP. Figures like Leila Khaled and Ghassan Khanafani remain well known and inspiring to millions who fight for Palestine. The organization, along with the DFLP, is also active in the armed resistance in Gaza as part of Al-Aqsa Flood, with its Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades.

The vision of the PFLP is not that of the past, but, in Lauesen’s phrase, the future. Rather than a pessimism that has led many to abandon solidarity politics that are not explicitly socialist, nor a naive idealism that romanticizes Palestinian fighters from afar, Lauesen offers a balanced assessment of the contradictions facing the Palestinian struggle today that nevertheless affirms the hope that past generations of revolutionaries died for. If it is indeed true that “all genuine knowledge originates in direct experience”[5], then here we may indirectly learn something from the experience of an anti-imperialist who did the real work to support that dream of Palestinian liberation, as we must all do now.

Transcript:

AIN –

Today we’ll discuss a little bit about The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine[6] and their role in the struggle for the liberation of Palestine and your experience with them as part of [the KAK]. So I wonder if you could just begin by talking a little bit about the PFLP, how it was created, when, what forces were part of it, part of the different tendencies at the time, of Nasserism, Pan Arabism, that were at play.

TL –

Well, the PFLP was established, as you said, by a trend of Arab Nationalism, which was very strong at the time. There were a lot of nationalist revolutions at the time – we had Nassar in Egypt, and we also had it in Syria and Iraq, and in the surrounding countries, and also in Palestine there was this Pan-Arab Nationalism and actually, the PFLP saw itself as the Palestinian faction of this Pan-Arab revolution, as much as a Palestinian revolution movement. So this was the beginning. George Habash[7] – I think he was a doctor in Beirut at the time, and together with other of these Pan-Arabnationalists, they founded the PFLP, because at that time we saw also on the general level, this transformation, from nationalism towards socialism in the Global South, and the PFLP was part of this trend, of this transformation – or radicalization – of the liberation movement at the time, with the inspiration from the struggle in Vietnam and the Chinese Cultural Revolution and also from the success of Che Guevara in Cuba, so it was kind of inspiration from Cuba, and Vietnam, and China which led to the formation of PFLP.

AIN –

To what extent did PFLP have a, would you say Maoist strategy at the time, with the strategy for the liberation of Palestine?

TL –

They had very much inspiration from Maoism at the time, and I also think that they adopted this idea of a popular liberation struggle, and armed struggle, and guerrilla tactics, and so on – and they should carry out some kind of armed struggle for liberation – which was a bit of a contradiction of the Soviet Union’s strategy for the Global South, or for the Third world at the time, so I will say that they were very much inspired by this revolutionary spirit coming out of Southeast Asia, but also they were inspired [by] Che Guevara and Cuba, of course.

AIN –

And to what extent did the PFLP have these international connections? Were they training in China at the time, before joining?

TL –

No, I don’t think so. No, they actually, as far as I know, received no substantial material contributions from China. China, at the time they carried out an extensive ideological propaganda for Palestine. They published a lot of Palestine material and posters and booklets and pamphlets and so on. But I don’t think they, at least they don’t, as far as I know, they didn’t receive arms and so on. They received a lot of books, of Mao and the Little Red Book and so on, but I don’t think they got any substantial material contributions from China at the time; it was more ideological inspiration.

AIN –

What were the main factions within the PFLP, and who were some of the main leaders or figures associated with different tendencies of thought?

TL –

Well, at the time it was of course George Habash and Hassan Kanafani and people like that. You can say that theredeveloped a kind of diversion in the PFLP, between a faction which wanted to carry out this kind of internationaloperation, and a faction which was more working on the local level in Jordan and from Jordan and from lebanon. But at that time they could actually make attacks from Jordan and from Lebanon into Palestine. They had their bases, first in Jordan and later on, in Lebanon, but besides that, they had this international operation, with the airplane hijacking starting in the late 60s, which was meant to place the Palestinian issue on the international agenda. They didn’t have, of course, a big military significance, it was more kind of putting the issue on the agenda.

AIN –

To what extent did the PFLP interact with other factions within the Palestinian liberation struggle, like the PLO?

TL –

There was of course the PLO and, you can see that the Fatah, which was led by Arafat, was far the greatest and most influential faction, which was a nationalist, but at that time also very much inspired by the Vietnamese, and other the kinds of armed struggle, so in terms of military strategy, it was very much similar, but Arafat was a more nationalistideology, while PFLP had a very strong both Pan Arabic vision, but also an international vision, they cultivated contacts with a lot of other liberation movements and also political parties in Western Europe and yeah. And of course, they have this socialist World-revolutionary outlook at the time and they actually also established sections in other Arabic countries. They had a section in Algiers and they had an underground section in Saudi Arabia and, of course, in Lebanon and Syria. They still had this Pan Arabic perspective on the liberation of Palestine. They thought it could only happen in the context of a wider revolution in the Middle East, radicalization of the [petit-bourgeois]régimes.

AIN –

You’ve mentioned, in some of the writings, especially from the KAK, about the decision to support the PFLP – there is mention of the fact that the PFLP had a connection or representation and support within the refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon amongst Palestinians. How did they develop this mass base of support within the refugee camps?

TL –

It was mainly on not only having, you know, the armed struggle, but also having a different kind of social projects -the health clinic, children care, and all kinds of social and cultural institutions, but also trying to develop a kind of party structure, where people could become members and become organized. And they also try to make youth organizations, and women’s organizations, and labor organizations, and so on. So they had to – they tried to develop this kind of broad perspective on the struggle – not only armed struggle, but also different kinds of, other kinds of social struggle and education in the refugee camps at the time, yeah.

AIN –

I’m curious to talk a little bit about your own experience with the PFLP. How did you come into contact initially with them and why did the organization view this group (The KAK) as the one to begin engaging with and supporting?

TL –

We started out as a group which supported the Vietnamese struggle in the mid 60s and the late 60s, and around ‘69,seventies, we saw that we had to enlarge that scope – the Vietnamese were not the only ones who were struggling and it seemed like they were winning. And who could be the new dynamic force in the Third world to develop this trend of anti-imperialism with a socialist perspective? And we traveled around the world and analyzed and looked after all the liberation movements and tried to – and we looked both in Africa and in Central America, South America, and of course also in the Middle East. And our eye was caught by, of course, the spectacular actions which the PFLPmade at the time. But we decided to take a trip to – some of the members [of KAK] took a trip to Jordan and also to Lebanon in the late 60’s – 68’? Something like that, and had a talk with PFLP, and also the group called DFLP and also Fatah and there was also Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command. There was a lot of organizations at the time which we had discussions with and for us it was important that the organization we wanted to support had a clear socialist perspective, and also that they were capable of developing a mass organization, and were in close contact with the masses and, we decided, to after these investigations, to support the PFLP. In 68 I thinkit was – yes – we started working together with them.

AIN –

And what did the discussions with them entail, as to what your organization would be able to provide, because I think in other discussions of other organizations, like the Red Army faction, they would go looking for weapons training -pistol training, for example – by the Palestinians but, as I understand, your organization went more to offer material support, with nothing in exchange from them.

TL –

Yes, because our organization actually didn’t need that kind of – I don’t think that the PFLP could offer us much help, and we needed much help, but they needed more. Our assistance, then – we didn’t need [the kind] of knowledge which they had, of radical armed struggle. [That knowledge] didn’t fit with the kind of struggle we had, so it was not necessary for us to have this kind of training, which they could offer, because this kind of training had no use for us. We were not planning to have some kind of armed struggle in our part of the world and they could not [teach] us any skills concerning working undercover in Denmark because they had no knowledge of how Danish society functions and works, and the mentality of people, and how the institutions worked, and so on and so forth, so we could not… acquire relevant skills from them, and they of course could need what we could offer of the material support. But we also tried to have a lot of political discussions with them, about the situation in the Middle East and how to develop the struggle.

AIN –

And what was the long term perspective of the organization at that time with the strategy for the Liberation of Palestine? In terms of conducting an armed struggle that you would help provide assistance for – What was the view within the PFLP other than, like you said, a wider revolution within the Arab world, of what would destabilize Israelsociety? You mentioned plane hijackings; was the PFLP ever equipped… have a protracted People’s War within Palestine? Or, as you mentioned, other times, the difference between Palestine and Vietnam, that there aren’t jungles to hide in, so this was not as feasible of a strategy.

TL –

Of course, the Palestinians’ revolutionary movement at that time was not capable of defeating the Israeli state, which was so much more superior and also with the full support of the United States and the rest of the world. So for sure it had to be a long struggle, and the liberation of Palestine had to be seen in context [of] the transformation of the Third World and the Global South, and the Global South in the longer run and in a longer perspective, but but as matter of fact, you can say that the Palestinians continued with their small scale armed struggle, but without a secure Base area, as in the Vietnamese forest or the mountains or any other, they just had the refugee camps as their base area and it was for sure or not secure – the base area was destructed by the Jordan Army in September 1970, leading to the defeat of the Palestinian movement in Jordan.[8] And they had to move to Lebanon, where they started thisexercise, building a kind of military force, which was very strong in Lebanon. But when they reached a point which became untenable for Israel, the IDF invaded Lebanon in 82’ in a huge military operation, looking like the one in Gaza now. [Israel] killed around 20,000 people in southern Lebanon and in Beirut, and they crushed again the liberation movement, which was then forced to move; Arafat moved to Tunis and PFLP moved eventually to Damascus in Syria and some of them went to Gaza, the remaining strip of Palestine. But again, Syria was for sure no secure base, and they had to make a lot of compromises with the Syrian regime because they were not – in Lebanon and Jordan, they had some kind of autonomy, because the Jordanian regime at the time, or the Lebanese regime, was very strong at the time, but their their autonomy in Syria was very limited with the Assad regime, so it was not a very secure and and good base, so you can say this military strategy which they had been exercising from the late 60’s up to the mid 80’s was not very successful and actually they stood without any kind of military and political strategy and these have, I think, been the problem for for the Palestinian left since that time – that they didn’t have a functional strategy.

AIN –

How did the logistics work, with respect to coordinating with the organization? Your solidarity work, for example, I know we’ve talked about having to meet contacts for the PFLP in the Eastern Bloc, in Sofia, or in Romania or whatever, and also the critical role that South Yemen played at that time as a

facilitator of the movement of money and supplies, but I imagine that, you know, the PFLP was under intense Israeli surveillance and your organization was at a certain point as well, so how did you navigate this difficulty of the Israeli surveillance and trying to give them the supplies.

TL –

Well, as you said, at the time the East Bloc was kind a of neutral area for us, where both the Western Intelligence Service and Mossad had limited operation possibilities. So it was where we could meet at the time we could fairly and discretely move to Eastern Europe through Berlin and I think they could also because the PFLP gradually developed a good relationship with the Soviet Union and the East Blocs so they could easily move to Eastern Europe. ThePalestinians got a lot of scholarships in the East Bloc and the Soviet Union, for engineers, for doctors, for all kinds of people. So there were a lot of Palestinians [who], through their political movement, got scholarships in the East Bloc so they had legitimate reasons to go to the East Bloc, so this was a way to meet. We didn’t have any contacts, of course, with the Intelligence Services of the East bloc and as far as I know they were not aware of our meetings with the Palestinians. I’ve seen no record of it, even if people have looked into the records of the East bloc Intelligence Service after the breakdown of the East bloc, I’ve seen no records of our contact with the Palestinians, so I think [PFLP] actually were discrete during the whole period. So it functioned in a good way.

AIN –

And I know the logistics of actually delivering the materials that you were working to give the PFLP was also quite tricky, and there is the story of the surfboard with the missiles inside of it, which you were trying to do a surfing trip to use as a cover for delivering materials, but what role did having a friendly state like South Yemen[9] at the time play infacilitating?

TL –

No role at all. I think it did for the Palestinians because they could get some kind of diplomatic passport or somethingfrom some of them – the members from Yemen – but we didn’t have any contact with the Yemenis side, no. We had good contacts but – this is a quite another story – we had a good contact with and were working together with comrades in Copenhagen who were very involved in the support of – not the Yemeni revolution – but there was a liberation movement in the Dhofar area in Oman, the Sultanate of Oman at the time and we were also involved in the material support work for this Liberation Movement (which was crushed actually mostly by British intelligence service and the British Military, in connection with Saudi Arabia I think at the time) which was happening just at the eve of the transformation of the Gulf Area from poor countries to rich Arab states, during the rise of the oil prices and also the nationalization-of-oil interest in the Gulf, and Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait, and so on.

AIN –

There’s a lot of talk about how Hamas was funded and enabled, in many ways, by Israel, just like the Taliban was funded by the United States, but to what extent do you think the PFLP was viewed as a very legitimate – or socialism was viewed as a very legitimate threat by the Israelis – and they had to take it out, and is that responsible for why the PFLP today is less of a significant actor in the Palestinian liberation movement than in the past?

TL –

I don’t know much about that but I’m sure that if you go back to the 70’s and even the 80’s for sure, Israel was looking at the PFLP and also Arafat – the Fatah – as a much bigger enemy than the small, Islamic part of the Liberation Movement at that time, but I don’t think that… Israel is responsible for the decline of PFLP. I think this has to be seen as part of the general decline of Socialist Liberation Movements in the 80s and in the 90s. So it’s not, it’s not only, you know, pure Palestinian or PFLP’s mistake, it’s part of a general trend in the past 20 years, that this kind of movement has less influence.

AIN –

And today, do you think the PFLP is an organization that can sort of reform itself and be a part of the major leaders of the Liberation struggle or it’s in need of a new Left wing organization within Palestine?

TL –

I hope so, because I don’t see that the strategy of Hamas, in the longer run, can lead to the liberation of Palestine. I think that the Liberation of Palestine is still very much embedded in the possibility of changes in the whole region and it’s linked also very closely to the decline of U.S. hegemony in the region, and I think that when this current war is over in some months, you can see that on on both sides, both on the Palestinian side but also on on the Israeli side – it’s a whole new game. We will see the development of different kinds of strategies when the war is over. I think that it is important to see that for the interests of Israel, and the interests of imperialism for the region is not similar. They are very different and I also think that what the West will do is that they will try to establish some kind of what they call the two state solutions – all the Western powers now call for 2 state solutions, not because they want to have a Palestinian state, but because they want to save Israel from itself, I think they want to create a Palestinian “Mickey Mouse State,” which could lead to some kind of settlement which would secure the state of Israel. And I don’t think – that state will not even be a state on the 67’ Borders, which means the state consisting of the West Bank and Gaza, and the eastern part of Jerusalem, because this would mean the dissolution of a huge amount of settlements in the West Bank. Half of the West Bank is settlements now and such a solution will not …at all be acceptable for Israel. So that kind of state would be part of the West Bank, a scattered part of the West Bank, and Gaza, and I don’t know what. The state will not have full autonomy, it will not have control of its own borders. [Palestine] will not have a regular army and .. just to create a political governance of such a Palestinian state – that will satisfy Israel and willsatisfy the West – will be very, very difficult. So I think that kind of Two-State Solution would be a strange “Mickey Mouse State,” which would not satisfy any kind of Palestinians’ ambition and therefore it’s a strange project. And the other option is that Israel will take over the control of the full West Bank and Gaza, with policing and army and so on, and it will also be a very unstable project, so I think that we are very, very far away from any kind of stable solution, so we will have to take a long perspective on the long struggle ahead. And I think also one thing more, which is important to point out is that this rather small attack of Hamas, which was about 1000 or 1500 people, only armed with hand weapons and they occupied some small settlements and villages for 2 days and 2.5 days and so, and then they withdrew – this limited military operation has created an avalanche of events on the world scale and has pushed so much the principal contradiction on the world scale, between the climate of U.S. hegemony and the rise of a more multi powered world. This limited operation has made a big push to this big world contradiction and it shows how unstable the world is that very small pushes can create a large event on a world scale, and it also shows theimportance of the agents – the important of an action in a situation where the world is so unstable and the possibilities of small actions – that a flat of a butterfly’s wing can create huge results.

AIN –

So in that sense, even though the Hamas attack, or this war will not be favorable in its conclusion – already, you know in the past couple of days, Israel is talking about their strategy shifting towards trying to assassinate the leaders of Hamas and then cripple the organization – even though that is the case, you still believe that this small attack will trigger ripples of contradictions, perhaps in Israeli society, between the settlers and the government, between Israel and the US, between different factions within the Palestinian movement. So in that sense, it is something that will intensify and move the contradiction forward?

TL –

Yes. As you can see how this war has created a distrust, towards the US and the West in the whole global South. [People of the Global South] don’t believe in the discourse of the West anymore, because they can see the hypocrisy of it, so in that way, the US, and the West, this war, and the policy of Israel is very damaging on a larger scale. Also on a longer perspective for the position of the US in the region of the Middle East, you can see that it has kind of united the Shia and the Sunnis, which have had many conflicts, but now this war has kind of pushed that contradiction into the background, and you can see how even Iran and Saudi Arabia also – their contradiction has been diminished. So it has changed many balances in the Middle East, which is unfavorable for the United States’ influence in the area. So in that way the Hamas action, again it has pushed a contradiction and changed the balance in the world and not in favor of the US, so in that way you can see it as – it has some kind of positive impact on what is going on in the world, even if it has not – I don’t know what’s.. [Hamas’s] perspective with this kind of action? For sure, they could have imagined the Israeli response. And I think it must have been a difficult solution to carry out the actions when you know the Israeli hard response. It’s not a surprise because we have seen it in Lebanon before, that the civilian cost ofthis kind of action is huge. But I don’t know what they have thought of the [future], if they had expected that Hezbollahwould have supported them, or they had suspected that other Arab countries would have supported them directly, [with] material and military. And I don’t think this will happen, but even then, I think that their small attack has changed much in the Middle East and in the world.

AIN –

Thank you for taking your time to discuss today, and it’s always a pleasure to hear your perspective. Thanks, Torkil.

Notes:

[1] Lauesen’s organization changed from the Kommunistisk ArbejdsKreds (KAK) to the Manifest – Kommunistisk Arbejdsgruppe (M-KA) in 1978.

[2] Not much exists online about the IRE, but see here for more: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/14818294

[3] For more on the KAK/M-KA, which is not discussed in this interview, see Turning Money Into Rebellion, edited by Gabriel Kuhn. See page 114, where Lauesen discusses the difference between their approach and other European groups like the RAF.

[4] Turning Money Into Rebellion, page 110.

[5] Mao Zedong, “On Practice”.

[6] For an evaluation of the PFLP’s Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine, see here: https://anti-imperialist.net/blog/2022/03/15/the-palestinian-left-past-present-and-future/

[7] For Habash’s biography, see here: https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/27109

[8] This civil war is known as “Black September”.

[9] The South of Yemen was the Marxist People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen from 1970 to 1990.